The Serpentine and Dartington Trust’s ‘Black Atlantic: Sensing the Planet’ symposium of art, music and talks contemplated the long imbrication between empire, colonialism and environmental destruction

Snaking through the paddocks of southwestern England by train from London to Devon – fields peopled by sheep, outhouses, pylons and the odd goat – the River Exe has broken its banks, and lively moorhens splash about in brackish waters. Rust-coloured cliffs swing into view as the train nears the Jurassic coast, sandstone stained red by sedimented iron oxide, the alluvial residue of however many hundred millennia of animal life. The train glides around Teignmouth harbour, where sailboats bob on the surface of the water, facing out towards the English Channel, the Celtic Sea and, beyond it, the Atlantic. My journey to Dartington Hall in Totnes is for ‘Sensing the Planet,’ a three-day symposium of art, music and talks about race and environmental harm. Gathered as a kind of counterpoint to COP26, amassing at the other end of the British archipelago, it contemplated the long imbrication between empire, colonialism and the climate crisis.

The estate of Dartington Hall has been settled for over a thousand years. This, then, is England: owned by the Fitz Martins in the twelfth century, nestled among Devon’s ‘deep valleys’ – from which the peninsula derives its name – Dartington passed through the Audeley family into the hands of the Crown. In the 1380s Richard II bequested its lands to his half-brother, the Earl of Huntingdon and first Duke of Exeter. By 1400 new buildings had sprung up in a double quadrangle, which today comprise one of the country’s most important unfortified medieval manors. Passing from the Plantaganets to Henry VIII’s wives Catherines Howard and Parr, its fate changed in 1599, when it was bought by the Champernownes, close kin of Walter Raleigh and Humphrey Gilbert, who led colonial expeditions to Virginia, North Carolina, Ireland and Guyana.

There is another history here too. Bought by Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst in 1925, heirs to both British gentry and the American Whitney family fortune, they began to reinscribe the property’s history under the aegis of rural reconstruction, gathering artists, agronomists and intellectuals such as the Bengali poet and polymath Rabindranath Tagore. In the 1930s it housed people fleeing fascism. In 1990 Schumacher College was founded there commemorating E.F. Schumacher, author of Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (1973). ‘Sensing the Planet’, says curator Amal Khalaf, builds on this standing as part of a raft of stately home ‘occupations’ in which imperial history is – even if fleetingly – overwritten. Dartington’s setting offered its cast of thinkers a troubling and complex historic furrow from which to speak, deepening and de-provincialising the discourse of localism long posed as an answer to the climate crisis.

Curator, activist and filmmaker Ashish Ghadiali was reading Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic (1993) when its author got in touch with him – “randomly, magically” – about a year ago. Ghadiali had recently found a place to live on the estate, having moved to Devon from London a few years earlier. “I was trying to orient myself in the landscape of South Devon,” he tells me. “It felt like an alien context.” It wasn’t just that everyone was white; it was a more expressly decolonial discomfort. Before long it fell into place that South Devon was just another “engine of empire,” a key site in the westward maritime expansion of the British empire, and soon he saw “that strip of sea along South Devon as being, in many ways, Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic” – the same sea that incubated the syncretism at the heart of black cultures in the West, and the most influential work by a thinker described by filmmaker Steve McQueen as ‘the foremost intellectual in the United Kingdom’.

Ghadiali was this year on the steering committee for COP26’s civil-society coalition, as a member of the global South-led collective The Wretched of the Earth, when the penny suddenly dropped: all the committee’s energy was flowing towards a purpose that didn’t nearly meet the scale of the problem; worse, it just meant more consumption. “That machine is so broken,” he says. At this moment of urgent crisis, “you’ve got nothing on the table, from the intergovernmental conversation, that actually amounts to a vision of ecological equilibrium”. That realisation led him towards a faith in the “deep imagination” of artists, activists and intellectuals. “How do we bridge the gap between the local and the planetary?” Ghadiali asks. “Those are the questions that will lead us on a path to actual climate justice.”

The exact calibration between the local and the planetary was at stake at ‘Sensing the Planet’, where the nihilism of bureaucrats was but one foe. “There are patterns of denial alive around us, in which the denial of colonial history has been made to interface with the denial of the pandemic, and the denial of the climate crisis,” Paul Gilroy says in his inaugural address to those assembled under the hammerbeam roof of Dartington’s Great Hall. If people are sceptical of the links between these things, the forces of ultranationalism, eco-fascism, Neo-Malthusianism and the alt right are already connecting them organically in a “shared psychic structure of denial”.

This demands a reorientation towards the local, Gilroy attests. Our moment calls for “a language of attachment to place, which is not a nationalist language,” and, on another vector, a repunctuation of time that says slavery wasn’t so long ago, nor is ecological crisis so far in the distance. “I think we’ve got to shift belief. How else are we going to convince everybody that we’ve got to manage with less?”

The activities of the organisation Right to Roam, a group which campaigns to reinstate public land as commonly held, started by environmentalists Nick Hayes and Guy Shrubsole, have interested Gilroy lately for their contention that “maybe people wouldn’t be so fervently, so absurdly, nationalistic, if they had a sense that the land around them was something they had a relationship with”. This shift towards a more “parochial frame” holds out the promise of a renewed relationship with the very soil beneath our feet suggests Gilroy, who has longstanding links with the South West. “In my own life, I’m coming to a much more determinedly local sense of dwelling and being in the world.”

Does this recentering of the local hold out dangers for us at our ghoulish conjuncture? “Of course this “relocalisation” has dangers but the risks of not accommodating something like it are even greater,” Gilroy responds. There is “no general answer” to the lure of nationalism. Local bonds cannot “undo the potency of racial hierarchy in a direct or overt way, but promise new possibilities and solidarities.” Britain’s “peculiarly colonial location”, Gilroy says, leaves us “squeezed between its ongoing imperial commitments and its pathological refusal to work through the past for which migrants, aliens, incomers and settlers continue to pick up the bill”. To speak from a contingent position, with its “partial ways of knowing,” is a “responsible and cosmopolitan gesture, not an alibi for some sort of provincialism”.

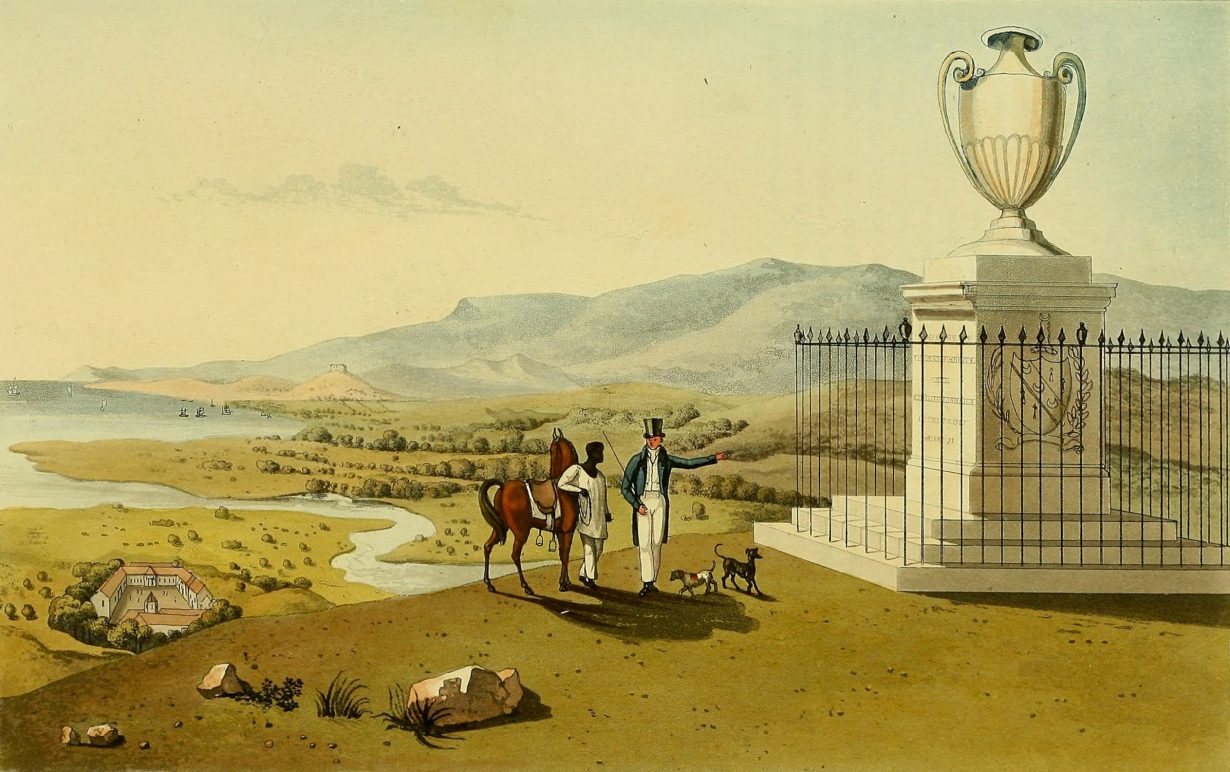

In a lecture at Dartington by Matthew Smith – who directs the UCL Centre for the Legacies of Slavery – the historian drew up a series of tranquil aquatints, bound with ‘gum arabic’, of the Jamaican countryside from the watercolourist James Hakewill’s A Picturesque Tour of the Jamaican Countryside (1825). Goats perch on parched hillsides while sheep graze by glassy streams. The people of this landscape are either absent or present as dots, while the ‘rural’ is conscripted into the visual lexicon of glamourised imperial domination. An alabaster monument straddles the hilltop, fenced off. Where records submerge certain stories, Smith says, “we’re trying to recover their lives with as much granularity as we can”.

Drilling down deep enough, Smith suggests, the earth “is full of networks of roots and connections that are traceable through black genealogies.” A similar idea is writ large in The Otolith Group’s O Horizon (2018), Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar’s contemplation of Tagore’s ‘ecosophy’ at Visva-Bharati, the college he founded in rural Santiniketan in West Bengal in 1921, which was screened at Dartington. Their film burrows into the soil’s strata, uncovering the colonial project of its robbery: “Marx talks a lot about the robbery of the soil in Ireland,” as did Tagore, Eshun said at the symposium, where the monocropping culture enforced by the British robbed the soil of its health. The ‘O horizon’ is biologists’ name for the topmost layer of organic matter, here depleted by centuries of extraction: “turning this barren land into a garden was an expensive and arduous task,” vouches one of the film’s soil scientists.

Devon has not seen the same prominence as nearby Bristol as a centre of decolonial activism, but its activities have had their own momentum. Groups including Exeter Decolonising Network and the Racial Justice Network were key constituencies at Dartington, organisations that have forced a reckoning with the Brexit-voting area’s history in institutions like the University of Exeter, which invited local Katie Hopkins to its campus in 2019. Malcolm Richards, who is part of Exeter Decolonising Network, moved to Devon from Hackney six years ago as a teacher, and is now doing a PhD. “I was ill-prepared for that transition”, he says. People would stare at him as he walked down the street, gawps that carried no hint of invitation or hospitality: “you are out of place”, their faces said.

“I was always a visitor,” Richards reflects. Many colonial identifiers – mixed race, black British – bracket so as to imply ‘alien’ origins, but don’t tie those they categorise to place. “If migration is part of your living memory, that gives you a particular connection to land,” he says: movement is more in your make-up. “My mum’s family are from Guyana and moved every two generations,” he tells me over breakfast. “They were always more comfortable with precarity, because they were used to it, it was a familiar pattern.” By contrast, “my dad’s family have been on the same rock in St Lucia for as long as they can remember – a rock, that’s what they call it. Their lives are literally inscribed in the stone”.

The photographs of Ingrid Pollard excavate that relation, rendering racialised people in rural settings. This is not, says curator Khalaf, a new conversation: Pollard has been having it for decades. These images trouble the formulas of country life: in Wordsworth Heritage (1992), a postcard originally erected as a billboard in Kings Cross and now shown in Dartington’s gallery space, Pollard and her fellow ramblers trope and subvert the mass-productions of English Romanticism by stealing the poet’s frame. The original postcard comes from The Cost of the English Landscape (1989), a disassembled collage juxtaposing mushrooms and yellowing ferns with monochrome images of people going walking. Ordnance Survey maps are overlaid with scrap-booked captions wryly jotting the paraphernalia of Wordsworth and Beatrix Potter. Warnings symmetrically emboss the assemblage like colonnades, sentries against leisure and pleasure: ‘KEEP OUT,’ ‘NO TRESPASS,’ these dictats read, while a young woman wearing a bakerboy cap, whose joyful face we recognise rowing a boat to the right, defies them, and mounts a turnstile.

There is a conviviality to these images. They thrum with the interdependency of life on earth, suggesting the ‘trembling’ archipelagos at issue in long conversations between Édouard Glissant and Hans Ulrich Obrist that were looped in the manor’s Tagore Room. Obrist (who says he reads Glissant every morning) tells me, as we wait for the train at Totnes, that this work wards against the twin pitfalls of homogenising globalisation and nationalism through “mondialité, which is a global dialogue, which can listen”. At Dartington, that dialogue found a local habitation and a name. “The thing that really resonates with Paul [Gilroy]’s work,” Richards says, more than the specific issues of land, or even of climate and racial justice on the table, is “the hope that maybe we can imagine something else”.

Travelling back to Paddington at dusk, my mind swims with these vigorous calls towards sensitive reimagining, a kind of historical braille that feels lives and stories back into scenes painted to pretend a forgetting. Braced by the train’s onward motion, I see figures and faces straked across the rolling hills. They have always been there. The train pushes forwards. Moorhens flap their wings in circles on the flooded plain.