From Kawanabe Kyōsai’s monsters at Royal Academy of Arts, London, to Zhang Ruyi’s urban detritus at UCCA Beijing: reflections on art and freedom

It seems a bit perverse to come up with a list of exhibitions and argue that you really need to see them at a time when all you can see is war. Granted this may be more the case in some parts of the world than in others. And perhaps it’s also true that the world is paying more attention to a European war than it has done in the case of recent conflicts in, say, Asia or Africa. But still, as the war escalates (at the time of writing), you get the idea of where ArtReview Asia’s mind is drifting. Indeed, it’s at times like these that art, and talk of art, seems to drift, more so than at other times, towards a realm of unreality. And from that cue, ArtReview Asia’s mind is drifting towards the words of John Berger, the late writer and critic who was among the mainstays of ArtReview Asia’s sister magazine ArtReview during the early 1950s. On 28 August 1968 (by which time he’d graduated to penning essays in New Society), a week after the then Soviet Union and other members of the Warsaw Pact had invaded what was then Czechoslovakia, following a seven-month period of political liberalisation known as the Prague Spring, Berger wrote: ‘Freedom of expression was crucial to the late Czechoslovak situation [meaning the Prague Spring]. Not because such freedom has an absolute value in all circumstances, as hypocritically claimed by bourgeois social democracy; but because this freedom during the last four months was the most direct means of reawakening the Czechoslovak people to a sense of their own political power.’ And perhaps what he’s getting at there is that at times when we feel powerless, freedom of expression, in whatever form, can serve to remind us of our own agency in the shaping of our social and political situation. Although that’s easier said than done when agency is precisely what a military occupation aims at depriving you of. And when the demand of those of us who still have a degree of agency is to look closely at what’s going on rather than to turn the other way and head through a gallery door. So with that in mind, ArtReview Asia offers these previews as an incentive rather than an enticement to view the exhibitions they describe as various expressions of freedom, of agency, of what Berger might have called art’s productive potential. Nevertheless, we’re going to start with monsters.

Kawanabe Kyōsai at Royal Academy of Arts, London, through 19 June

This month sees the first UK exhibition of work by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–39) in almost three decades. The son of a samurai, Kyōsai was active during the end of the Shogunate era and the beginning of Japan’s period of modernisation; his formative experiences included finding a severed head in the Kanda River, while his work bridges formal traditions (ukiyo-e) and popular forms, featuring contemporary caricature alongside subjects drawn from folkloric, Noh and religious tales. Forget the calm stereotypes of Hokusai; Kyōsai is wild style. All of which led, in turn, to the occasional arrest, a series of ‘drunken paintings’ and live-painting performances of works in the shunga (sexually explicit) style. As well as the creation of what is often credited as the first manga magazine (Eshinbun Nipponchi, in 1874). One look at his Pictures of One Hundred Demons (1889), for example, will make clear the extent of his influence on contemporary artists ranging from Takashi Murakami to the late Hayao Miyazaki; but more important in the current context is his determination to reflect in his art the reality (or messy nature) of the world around him regardless of the constraints of tradition and style. London’s Royal Academy features a selection of rarely seen works from the Israel Goldman Collection and should serve as a reminder of what is possible when artists are bold.

Fujiko Nakaya at Haus der Kunst, Munich, through 31 July

The daughter of a physicist who created the world’s first artificial snowflake, Fujiko Nakaya is best known as the creator of a series of ‘fog sculptures’. Although she herself resists the idea that she has any control over her primary material: ‘I create a scene so that nature can express itself within. I am a sculptor of fog, but I do not attempt to shape it,’ she said on receiving the 2018 Praemium Imperiale prize for sculpture. Nakaya instead credits Earth’s atmosphere for acting as a mould for work, which, on a grander level (depending on your point of view, of course), seeks to manifest a dialogue between artmaking, nature and technology. This last is an extension of the work begun when the Japanese artist was a member of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), alongside colleagues such as Robert Rauschenberg and Julie Martin. The culmination of E.A.T.’s work together came at Expo ’70 in Osaka, where Nakaya designed a cloud of water vapour to cover the Pepsi Pavilion’s geodesic dome. While it’s for such forms (or nonforms) that Nakaya is best known today, she also played a key role in the development of video art in Japan, helping to organise some of the first exhibitions of video art in the country during the early 1970s, while also working on community-based videoworks and video sculptures, and opening one of its first video-art galleries in 1980. At Munich’s Haus der Kunst, however, it’s the fog sculptures that take centre stage with their constant dialogues between transparency and opacity, freedom and control.

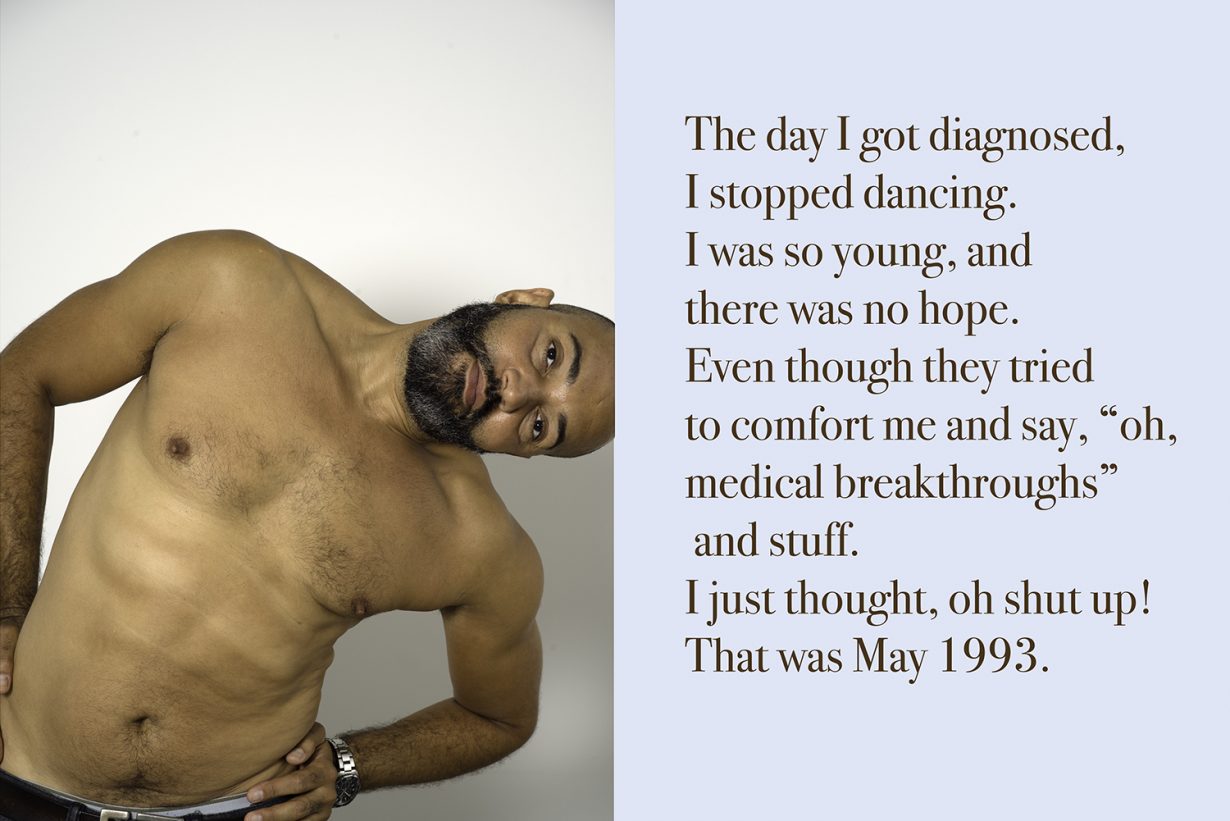

Sunil Gupta at Studio Voltaire, London, through 1 May

It’s freedom, of a different kind, that’s also the fundamental subject of Sunil Gupta’s current exhibition at London’s Studio Voltaire. Since the 1960s, the India-born, London-based Canadian has spent much of his career responding to the injustices suffered by gay and migrant communities worldwide, from early street photography in New York (Christopher Street, New York, 1976), through to explorations of the lives of gay Indian men (Exiles, 1986–87), mixed-race relationships (‘Pretended’ Family Relationships, 1988, which also responded to the UK government’s Clause 28, which forbade the promotion of homosexuality) and the New Pre-Raphaelites (2008), which was produced to support the fight to repeal Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which proscribed homosexuality and had stood since colonial times. His latest exhibition, Songs of Deliverance Part I and Part II, is the product of a year spent in residence at two London hospitals – St Mary’s and Charing Cross – during which he invited LGBTQIA+ people from the adult HIV Clinic and Gender Affirmation Surgery service to collaborate on a series of largescale photographic portraits of their lives. The works, which elaborate on Gupta’s longstanding interest in healthcare as part of the queer experience (he is openly HIV positive), are also on show in both hospitals.

Cui Jie at Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea, through 12 June

Shanghai-based painter Cui Jie is acclaimed for collaged portraits that explore the erasures, homogenisation and sense of constant flux that come in the wake of the rapid urban development of her homeland. Focal Point hosts her first institutional show outside China, which sees her expand the discussion to incorporate modernist factories and worker housing on the UK’s Essex coastline placed in dialogue with studies of a Worker’s New Village in Shanghai. Architecture, for her, is the product of history. On the one hand, her paintings explore the ups and downs of historic visions of Utopia; on the other hand, they seek to unpick architecture as the product of social and political imperatives.

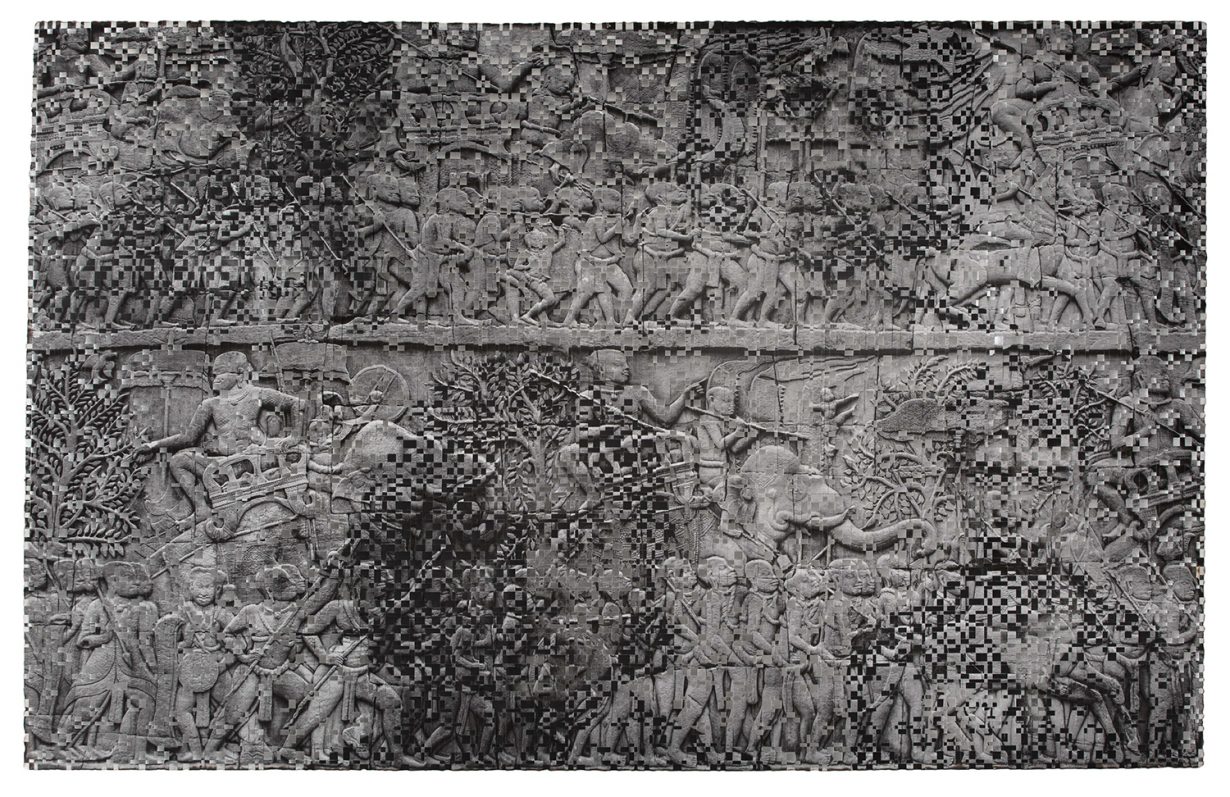

Dinh Q. Lê at Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris, through 20 November

Inspired by the memory of his aunt weaving 5 mats, Vietnamese American artist Dinh Q. Lê developed a photoweaving technique (mixing strips cut from a variety of found photographs, mounted on fabric) that blends a variety of images and registers (archival, press, pop cultural) into a new photographic whole. In this way, the artist replicates the deconstructive and constructive path of history, the polarities of migrant experience, and the relation of people and objects to contexts located in time and space. The Thread of Memory, on show at Paris’s Musée de Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac offers a survey of 20 works spanning 15 years of production.

Wong Ping at Times Art Center, Berlin, through 26 June

Hong Kong artist Wong Ping tackles the alienation of modern life (and particularly modern life in Hong Kong) with a mixture of humour and a sense of the absurd (he has previously compared his work, which generally takes the form of video animation, to standup comedy, arguing that humour makes his work more digestible). At Berlin’s Times Art Center he’s showcasing a new videowork and site-specific multimedia installation in a show titled Earwax. The centre’s exterior is wallpapered in a computer-generated self-portrait in the form of a Robinson-style projection that maps the artist’s face in tiny features, bookended by giant ears. Inside, a further giant ear (this one sculptural, made out of metal, which the artist describes as giving it ‘bell-like’ properties) has a series of table-tennis balls hurled at it (via the ping-pong equivalent of a tennis-ball launcher), which then bounce off, having made it ring. In the basement video, the head speaks: “As an activist, I began to get used to working from home,” it says robotically. “Signing all kinds of petitions has become my new hobby.” Which might well summarise the state of activism in general in the age of social-media. As a meditation on the introverted life experienced during pandemic-inspired lockdowns, and the constant bombardment of our own eardrums with more or less meaningful messages, Wong leaves us with a conundrum: whether (defensively) to let the earwax build up or whether to carefully examine what caused it to accumulate in the first place.

Nguyen Thái Tuan at Sàn Art, Ho Chi Minh City, through 23 April

On the face of it, the paintings of Nguyen Thái Tuan offer a rather more dismal outlook on life, featuring blacked-out bodies in decrepit, albeit rather baroque interiors, or people and animals encountering even more ruined exterior architecture. The title of his latest show at Ho Chi Minh City’s Sàn Art (a space cofounded by Dinh Q. Lê), titled Waiting for the end of the wind, does little to lift the mood. Heritage, in the form of either architecture or objects, seems disconnected from the anonymous people in his work, leaving them feeling like Samuel Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon, everymen and no men, passive and potentially ignorant, trapped in some sort of meaningless colonial (for such is the nature of the objects that populate his interiors) ritual. (Interior #12, 2018, for example, features a blacked-out body occupying one of a pair of ridiculously ornate thrones.) As a viewer, you seek to construct narratives that might lead Tuan’s characters out of their greyish daze (or at least construe a logic for their being there in the first place), to act in the empty space of the landscapes or occupy the lifeless blacked-out corpses. And in that sense they trigger an engagement that is as much creative as it is bleak.

Present Continuous / Sekarang Seterusnya at Museum MACAN, Jakarta, through 15 May

Walking an altogether less lonely road is Jakarta’s Museum MACAN, where Present Continuous / Sekarang Seterusnya is a collaborative project, initiated in response to the isolating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and aiming at giving voice to artists and arts organisations from across Indonesia and the realities that confront them. While the project incorporates talks, workshops and online discussion programmes, the central exhibition features four artists, two collectives and five curators from a geography that spans Banda Aceh, Bandung, Majalengka, Makassar and Jayapura. While community and the organisation of it forms a core theme, the exhibition as a whole tackles issues of indigenous politics, collective and historical memories, human relationships with sound and plants, and the potential of artist-led ‘creative industries’ to produce social and economic change. Quite some ground.

Wael Shawky at M Leuven, through 28 August

It’s questions of social change engineered by modernisation in his native Egypt and the Middle East, alongside questions of national, artistic and religious identity, that forms the bedrock of Wael Shawky’s oeuvre, which is the subject of a major retrospective, titled Wet Culture, Dry Culture, at M Leuven in Belgium. The exhibition features key works including parts of The Cabaret Crusades trilogy (2010–14), an attempt to retell the history of the Crusades from an Arab perspective (channelling the work of Amin Maalouf) via the medium of puppet theatre. In the video Cave (2004), which typically for the artist mixes historical and contemporary culture, Shawky wanders around a supermarket reciting verses from Surah 18 of the Qu’ran, which concerns a group of youths who retreat to a cave for 300 solar years in order to maintain their faith in the face of a kingdom that’s enforcing idolatry. “It’s about the idea that as a human anyone can be that isolated, living his or her entire world in a supermarket”, the artist told ArtReview back in 2016, unknowingly presaging many people’s lockdown experience. But perhaps that’s what makes Shawky’s work so persuasive – as much as it appears to be embedded in the specifics of particular cultural and geographic contexts, it also connects to wider human and social experience. Not to be missed.

Nazgol Ansarinia at Green Art Gallery, Dubai, through 7 May

Tehran-born Nazgol Ansarinia’s work spans a variety of media, but in the main traces the systems and networks that inform her daily life before expanding them to include larger social structures and ultimately aiming at locating a place for subjectivity in a globalised world. Her latest exhibition, Lakes Drying, Tides Rising, at Green Art Gallery in Dubai, focuses on water as an integral component of Iranian architecture, tracing the history of the shallow pools (howz) that once featured in private homes and gardens, both as a humidifier and a site of household activity, many of which are now dry, as a space of collective desire and sociability through a series of sculptures, videos and drawings. In the face of Tehran’s water and power shortages, Ansarinia refigures water as a site of nostalgia and a global resource crisis, as well as a reflection of Earth’s changing ecosystem.

Chim↑Pom at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, through 29 May

Very much embedded in the contemporary context is the Japanese collective Chim↑Pom, whose first major retrospective, Happy Spring, is on show at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. Over the years, its often provocative work has tackled themes such as overconsumption, nuclear devastation, migration and border controls, and the influence of mass media with often outrageous social interventions that mix humour and critique. Build-Burger (2016/2018), a fast-food-style stack of square sections of the fourth, third and second floors (plus any attached fixtures and fittings) of Kabuki-cho Shopping Center Promotion Union Building in Tokyo, liberated shortly before the building was demolished, was a critique of Japan’s mass-consumption (demolish and rebuild rather than renovate) of its cities. Meanwhile projects such as SUPER RAT (2006), Black of Death (2007/2013) and A Drunk Pandemic (2019–20) tackle social approaches to vermin and disease and the ways in which these last respond to and resist any attempt at control. Which, as it does, you might conclude is a portrait of Chim Pom itself.

Role Play at Prada Aoyama, Tokyo, through 20 June

Over at Prada’s flagship Aoyama store, in Tokyo, the fashion company’s cultural wing, Fondazione Prada, is staging Role Play, curated by Aperture magazine’s editor-in-chief, Melissa Harris, and exploring the projection and adaptation of alternate identities, alter egos and multiple selves in contemporary culture. According to Harris, the theme relates to the embodiment of otherness, forms of activism or empathy, or a means of ‘manoeuvring through entrenched or polarised positions’. The works on show include photographic series by Juno Calypso and by Tomoko Sawada, an audiowork by Beatrice Marchi, a series of portraits by Haruka Sakaguchi and Griselda San Martin, and a two-channel video by Bogosi Sekhukhuni. You’ll have to visit it yourself to see the extent to which it’s about being who you really are or being who you want to be. But perhaps that amounts to the same thing.

William Kentridge at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, through 29 May

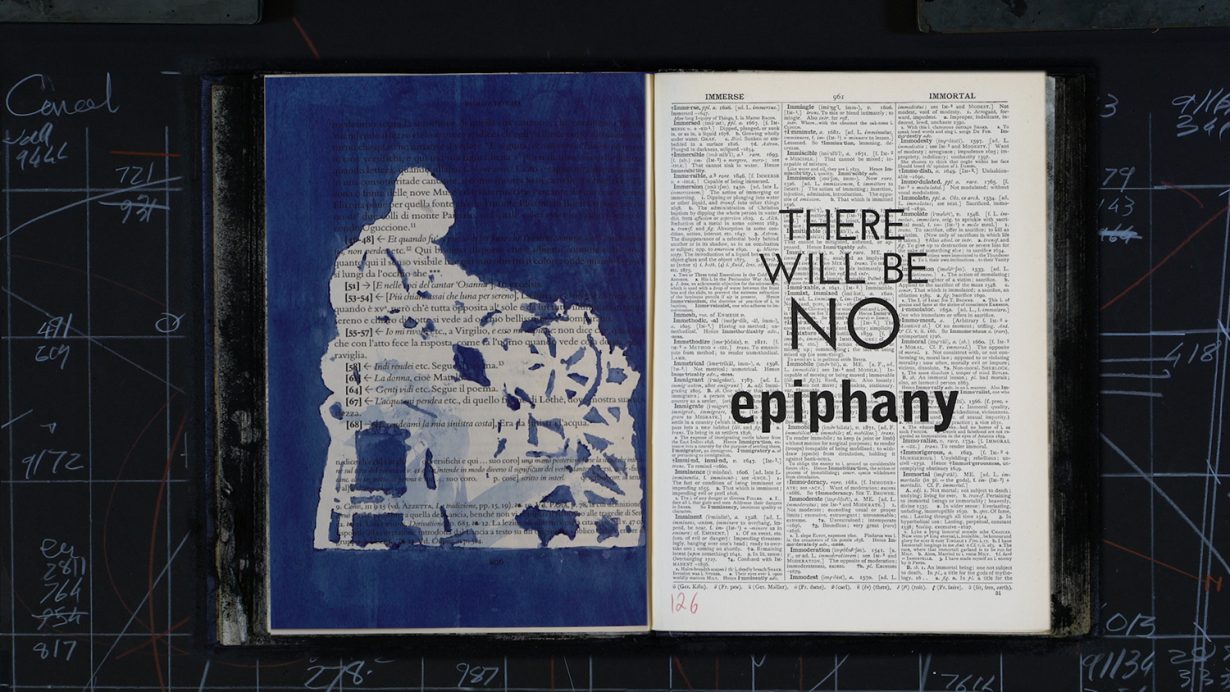

But for now it’s back to the cave. William Kentridge’s stop-motion animation Waiting for the Sibyl (2019) was originally created in response to an invitation from Rome Opera to make a companion piece to Alexander Calder’s Work in Progress (1968), which featured the American’s signature mobiles. As a means of exploring

the themes of turning and motion, the South African artist took the image of the Cumaean Sibyl, a prophetess who lived in a cave near Naples and to whom people would come to ask questions of their fate. She, in turn, would write answers on oak leaves and place them on a pile outside the cave. But the wind would blow the leaves around, leaving her supplicants uncertain as to whether they were gathering their own fates or someone else’s entirely. A metaphor, according to the artist, for the uncertainty of life. Kentridge’s video, on show as part of Weigh All Tears, a survey of recent work (spanning works on paper, sculpture and, of course, video) at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, features the turning pages of what looks to be a dictionary. As they flip back and forth, blowing debris and animated figures, coloured geometric shapes and oak leaves (naturally), as well as cryptic typeset messages (‘I have brought news/I have forgotten the message’ say the texts imposed across one spread) emerge from the dense type and dance across them. A therapeutic discourse perhaps on the uncertainties of now.

Sun Xun at Shanghart, Shanghai, through 26 April

Over at Shanghart in Shanghai, it’s Beijing-based Sun Xun’s animated feature Magic of Atlas (2021) that forms the basis of his exhibition, An Infinite Journey. The exhibition focuses on Luocha, one of six countries that feature in the film, this one ruled by three donkeys. The works (some made for the movie, some made since) take the form of coloured woodblock reliefs detailing the characters and scenography from the animation and combining traditional forms with elements inspired by Western comic-book iconography and Japanese animé. There are besuited, humanoid pigs, cows, chickens and rams, orthodox churches, avatars of science, soldiers and machine gunners that lead you beyond time and space to, well, someplace else. Although the place where all this is on show is currently under lockdown, so you might want to check before you travel. But you’re used to that these days anyhow.

Zhang Ruyi at UCCA Beijing, 30 April – 31 July

Back in the real world, well, Beijing, to be precise, Zhang Ruyi’s sculpture and installation are on display at UCCA Beijing. The Shanghai-based artist takes the detritus of urban life and the architecture of private dwellings and recombines them in ways that focus on the psychological effects of city life. In Potted Plants (2016), for example, a potted cactus (of the type many people acquired during lockdowns) is attached to a wall made of a grid of bathroom tiles. On either side of the cactus are concrete models of residential tower blocks, bound to the plant by string. The whole brings interior into conversation with exterior, nature into conversation with the urban condition, and asks viewers to find the place between these four poles in an absurdist dance of alienation and connection: perhaps the truest reflection of contemporary urban life.

Ugo Rondinone at Kukje Gallery, Busan and Seoul, through 15 May

and Scuola Grande San Giovanni Evangelista, Venice, 20 April – 17 November

On a similar note, but with very different results, Ugo Rondinone describes his upcoming exhibition at the Scuola Grande San Giovanni Evangelista in Venice as an exercise in coaxing ‘the sublime from the subliminal’. Burn shine fly derives its title from a book of poems by the New York-based Swiss artist’s late partner John Giorno titled you got to burn to shine (1994) and features ‘iconic’ works (although the precise nature of these works is under wraps at the time of writing, his best-known works, which generally combine humour and pathos, include stacks of car-size boulders painted in various luminescent colours, electric rainbows, ghoulish oversize masks, and a series of rather creepy, collapsing, but equally vibrantly costumed clowns). Meanwhile, in Kukje Gallery’s Busan and Seoul spaces the artist is exhibiting a series of five works from his nuns + monks series (2020), a group of totemic sculptures that explore the embodiment of the physical and the mystical within the titular forms, and once again, the transformation of humble stones into something more than stones (while retaining, one hopes, a certain sense of humility).

Venice Biennale, 23 April – 27 November

And with humility in mind, you’ll be off to explore the Venice Biennale, the international artworld’s first big semi-post-COVID jamboree. There you’ll be able to decide for yourselves whether it’s all an expression, an invitation into the unreal or a useful meeting point for the exchange of views and viewpoints and useful propositions for a world to come.

From the Spring 2022 issue of ArtReview Asia