Lonely Vectors at Singapore Art Museum chronicles the alienating effects of a world organised by a capitalist logic, and suggests strategies for emancipation

Be like water, my friend. Ho Tzu Nyen’s latest VR work takes Bruce Lee’s dictum one step further: participants don’t merely become water but pass through its many states, transforming from solid to liquid to vapour and back again (H is for Humidity, 2022). With my headset strapped on, I melt into water, swim alongside fish, pass through walls, rise into the sky, enter a heavenly sphere of colour, fall as rain and land on earth again – as the stiff humanoid avatar with which I had started this journey.

Insides rearranged, I am off to ponder the rest of Lonely Vectors, a group exhibition that is concerned, broadly, with a crisscrossing global flow of things, people and ideas, and which traces how these movements are influenced by wider political and social forces. For example, the experiences of low-wage migrant labour in Singapore come under scrutiny in Bo Wang’s Fountain of Interiors (2022), a column constructed out of the harsh fluorescent light tubes often found in workers’ dormitories to create a gigantic, blinding light stick. This glowing pillar is surrounded by fake potted plants commonly seen inside air-conditioned malls; the combination creates a sinister and suffocating vision of the controlled, plasticky interiors of such sites of capitalist consumerism and its modes of exploitation.

While the exhibition charts the forces that direct the global circulation of goods and labour, it also suggests ways in which these dominant power structures can be resisted. One strategy is a philosophical one, a sort of creative self-hacking to embrace formlessness; for example, one could, à la the shape-shifting H is for Humidity, be like water; or one could take a leaf from Shu Lea Cheang’s UKI VIRUS SURGING (2022), and be like a virus. In Cheang’s series of animated videos set in a digital wasteland, redundant humanoids are discarded by biotech industries and left to roam among broken computer parts. A character called Uki glitches and morphs – first in horror then in glee – eventually reemerging as a computer virus to reclaim her freedom and mobility.

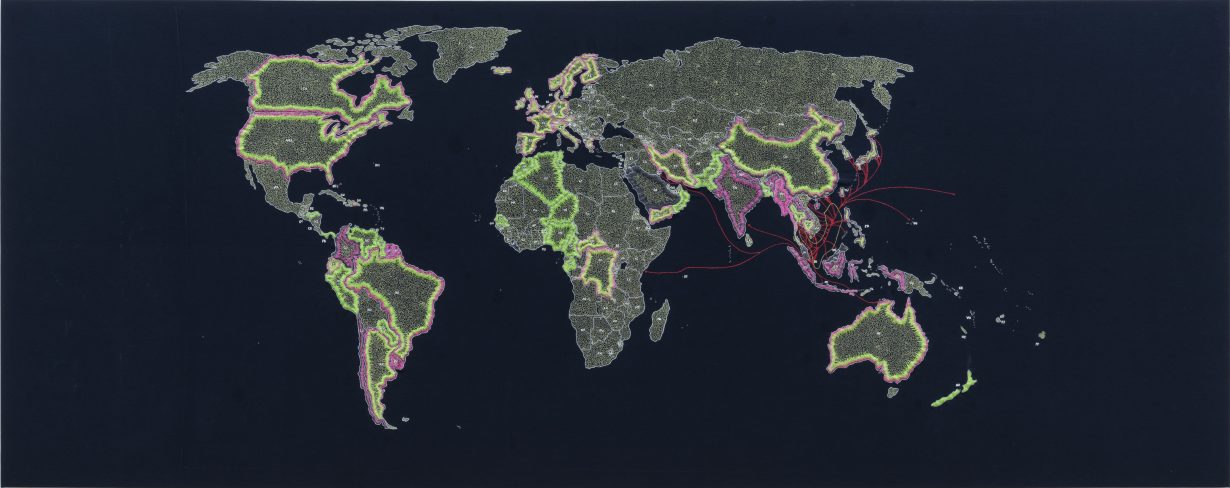

Lonely Vectors also includes concrete emancipatory practices that champion social and ecological justice. A powerful recurring theme in the show is counter-cartography, which subverts the common idea of maps as objective and universal tools for geographical knowledge, revealing, for example, the realities and experiences of marginalised groups in society. Highlighting the Vietnamese refugee experience is Tiffany Chung’s embroidered map, reconstructing an exodus history: boat trajectories, ports of first asylum and resettlement countries (2017), which plots the movement of refugees between 1979 and 1989 after the fall of Saigon. In this work, intricate red lines fan out from Vietnam to the rest of the world, presumably tracing the escape routes. Meanwhile, intense pink and green stitches cover the outlines of certain territories. Some countries are pink or green only; some are both. As with many of Chung’s works, the viewer is not given any legend. Does the pink refer to the ports of first asylum or resettlement countries? What is suggested by the bare data presented – long journeys, provisional refugee camps, the limbo state of uncertain settlement – is poignant enough. The withheld information also suggests a respectful acknowledgement that there may be parts of the past that remain inaccessible.

Also mapping against the grain is Cian Dayrit’s Penitent Plant (2022). For this work, the artist collaborated with banana plantation workers in Mindanao to make hand-drawn maps of where they worked, each populated with drawings, anecdotes and information on ancestral lands before they were taken over by plantations. Extrapolating from the material in these documents, Dayrit created (with the help of his regular collaborator Henry Caceres) an embroidered textile that serves as a rallying cry for social justice. In it, an outline of a banana plant is surrounded by names of big food corporations like Del Monte and Dole, and slogans in English like ‘Down with feudalism’, ‘Land to the tillers’ and ‘Rise up for food sovereignty and climate justice’.

Rise up, indeed. While Lonely Vectors chronicles the alienating effects of a world organised by a capitalist logic, it also envisions a world where such certitudes can be dissolved or challenged, so that more equitable futures can be imagined. Part of me wants to applaud its leftist, anti-imperialist stance, which makes it stand apart from the passive neutrality in most sam shows. Another part of me thinks, well, it’s about time. As museums around the world rethink their roles post-COVID 19, it often involves taking long, hard looks at the systems that underpin our current realities, and projecting into other possible futures. Lonely Vectors is a good start.

Lonely Vectors at Singapore Art Museum, through 4 September