“It was disturbing to see how menstruation – the only thing that moves the human species forward – forces women into exile”

“I’m identified as a ‘period activist’. It’s nothing to be ashamed of,” says Indian artist Poulomi Basu. Basu’s ongoing multimedia project Blood Speaks (2013–) has been presented via different platforms including editorial pieces for National Geographic and The New York Times, photobooks, exhibitions (from mainstream photography festivals like Cortona On The Move, 2018, to a fundraiser for Human Rights Watch in Sydney, 2016), as well as charity campaigns with Water Aid and Action Aid, but it first took shape as a series of photographs made during a trek through Nepal. “I’d met Emily Graham, who was the photography manager at Water Aid at that time, and we’d been discussing stories that were water- and hygiene-related. We were thinking about how water affects status, dignity and violence against women,” she says. The resulting photographs were published by Water Aid and subsequently distributed by mainstream media outlets like Time. “I grew up in a home with all kinds of taboos, and it was an extremely violent, patriarchal and misogynistic environment. I saw how these things were related and became interested in exploring the complex web of patriarchy. It was disturbing to see how menstruation – the only thing that moves the human species forward – forces women into exile.”

The practice of chhaupadi, the Nepalese-Hindu tradition of isolating women during their menstruation cycle, is born of shame and superstition. While there is no single source for this, it is often tied to the story of Indra’s execution of his guru Vishvarupa and the curse that resulted from it. To alleviate his curse, Indra (the king of heaven) distributed it among four entities: the land, the trees, the rivers and women. In women, it was said to manifest as the menstrual cycle, with the blood releasing the sin and therefore rendering the women and everything they touch or come into contact with impure. Another form of the ‘untouchability’ that characterises India’s pernicious caste system.

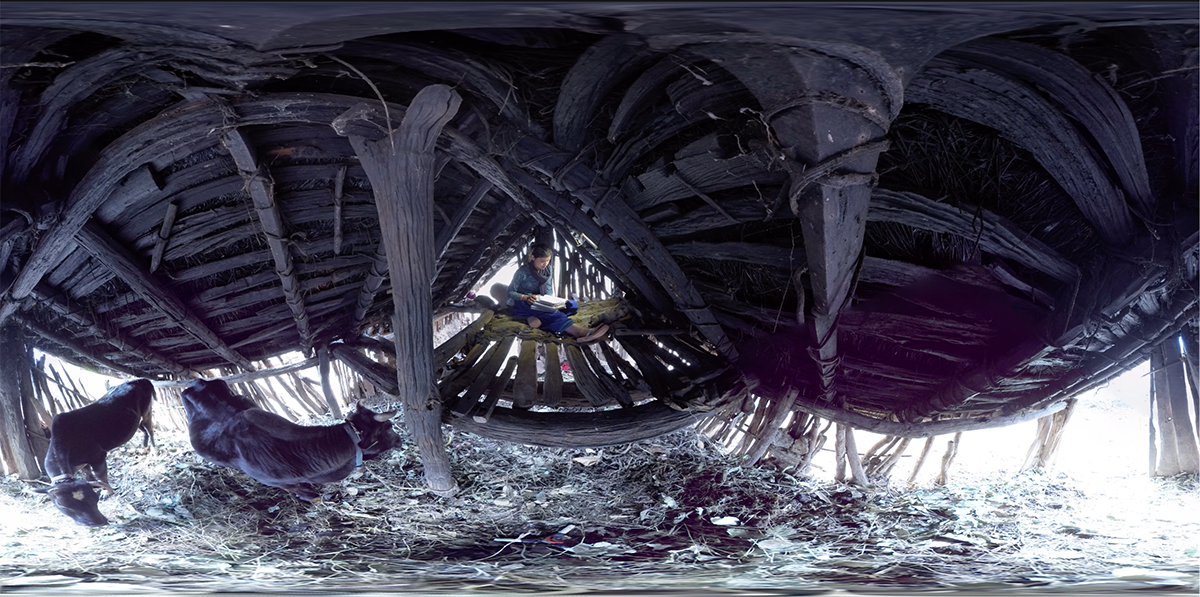

A centuries-old custom, chhaupadi is particularly common in the rural Western regions of Nepal, such as Karnali, where reproductive health education and clean water are hard to access. Women who are on their period, or who have just given birth, are exiled to huts and sheds (chhau goths) until they stop bleeding. Strict observance of chhaupadi means that a woman cannot enter the house, she is prevented from looking at the sun, she must not drink dairy products or interact with livestock or men, and she cannot touch fruit trees or collect water from a well. It’s believed that breaking chhaupadi will bring catastrophe to the community.

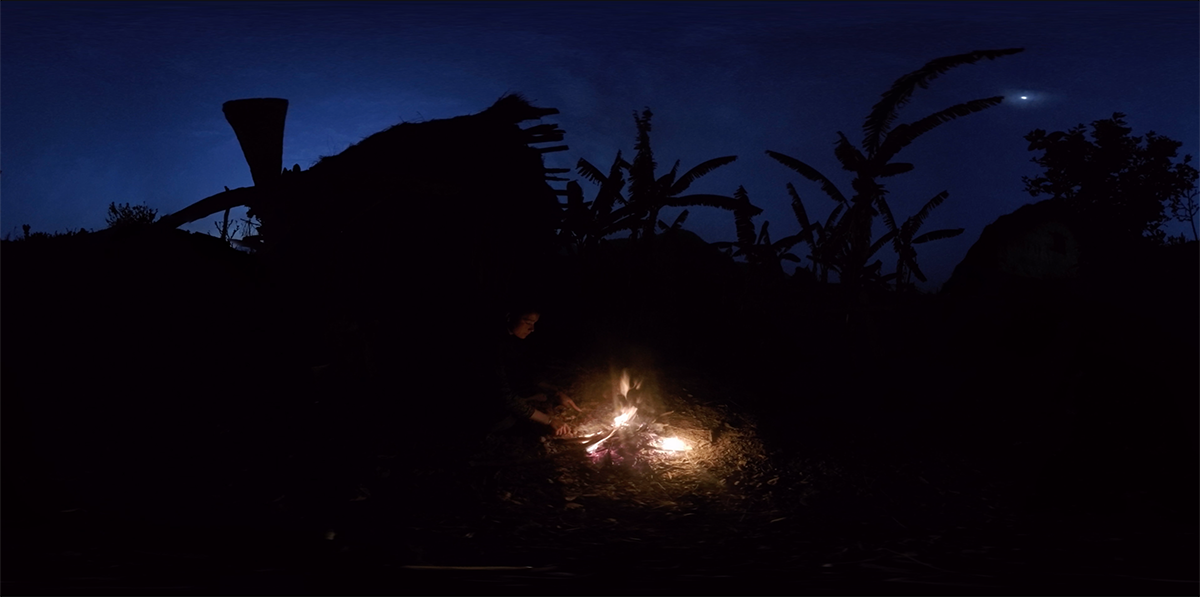

Despite being outlawed in 2005, the practice continues to be performed and women continue to suffer from poor menstruation hygiene resulting in infections, are subjected to mental and physical abuse, and are fearful of rape while exiled. They (and in some cases young children who stay with them) continue to die from exposure, snake bites or carbon-monoxide poisoning caused by the fires they build inside poorly ventilated huts.

In 2017 Basu developed Blood Speaks into a virtual-reality installation titled A Ritual of Exile. She calls it an “expanded form of storytelling”, with the intention of creating a more visceral experience that makes a connection between the audience and the women. At Cortona On The Move Blood Speaks was installed in two rooms: in the first room, a dimly lit exhibition space with photos in light-boxes forged intimacy; in the second, videos were projected across walls showing the Nepalese women in their chhaupadi environments looking directly at the camera, and by extension the viewer. In the middle of the room was the VR experience. Created by placing cameras inside various chhau goths and the surrounding environment (sometimes near the family home, sometimes kilometres away in a forest), the installation is an immersive and interactive experience, wherein the women undergoing chhaupadi are able to tell visitors about their own stories of isolation and ritualised violence.

At a conference during the 2019 South by Southwest Film Festival in Austin, Texas, Basu describes VR as a “triadic model that embraces the photographer, the photographed subject and the spectators as participants [and] reconfigures the condition of ‘untouchability’ within the first-world space of the white cube”.

Though she remains sceptical of VR as a means to foster empathy with any given audience, whether film festival-goers or art gallery visitors, Basu believes that “it can break the power dynamic and shift the agency towards the women who came forward to tell us about their experiences. Women who are menstruating are seen as polluting agents: untouchable. Growing up, our bodies were exposed to a lot of injury and pain, and so the storytelling had to come from within the house. I wanted to make people understand what shame felt like. Photographs can do that too – they can show what shame looks like. It can show how, by the time you reach menopausal age, your self-esteem is completely broken. This was the reality for most of the women I met for Blood Speaks.”

Since beginning the project, Basu has worked with activists in Nepal and on charity campaigns including Water Aid’s ‘To Be A Girl’ and Action Aid’s ‘#MyBodyIsMine’. She calls them her coalitions, and alongside these allies Blood Speaks helps chip away at the stigma attached to, and violence perpetrated upon women who menstruate. But Basu’s work also highlights the difficulty of breaking the cycles of abuse that occur under the guise of tradition: “Both my mother and I went through profound abuse, and my mother continues to live in a house of domestic violence. We were beaten up. There’s a codependency between the victim and the perpetrator that’s difficult to separate. I’ve seen how normalised violence is, even for my mother. She keeps thinking it’ll get better, but it will never get better. I had been able to run away and make a life for myself, but she couldn’t. And I see that in a lot of the women I work with. So it’s important to create a space for women to be able to talk about and share their stories. It’s about bringing visibility and some form of dignity and empowerment back into their lives.”

“The story of menstruation is linked to the story of domestic violence. If you’re a South Asian woman, you will know the kind of violence women go through in this part of the world. Blood Speaks is about passing the agency back into the hands of these women who are exiled for menstruating, to make their voices heard in their own way.” Collectively, campaigns by the Nepalese government and NGOs, both of which Basu has contributed her work to, have shed light on the physical and mental dangers of chhaupadi, resulting in the 2017 strengthening of laws prohibiting the practice, including sanctions of three months in prison and a fine of 3,000 Nepalese rupees for those who would enforce the exile. Despite these penalties and efforts of the Nepalese government to physically demolish the chhaupadi huts, there is a reluctance to change such deep-rooted traditions and superstitions. Chhaupadi and the menstrual taboo are reinforced by religious events like Rishi Panchami, which takes place in the autumn and requires women of menstruating age, who can be identified by red or pink garments worn during the festival, to purify themselves by carrying out rituals that include bathing in cow dung, urine and milk, washing their genitals 365 times, brushing their teeth with a Datiwan stem and fasting.

In 2020 the first person to be convicted for the death of a woman forced to practise chhaupadi was able to cut his prison sentence short by paying an extra fine. “Fines and arrests have only now just started happening,” says Basu, “but it doesn’t change hearts and minds.” So she continues to work on Blood Speaks, believing that art – in different forms – can access different audiences to get them thinking about why taboos and policies have not already changed. Basu is currently in the process of creating an animation, with plans for a graphic novel (which she hopes to publish cheaply, for distribution among the rural Nepalese communities she works with) following close behind. And looking beyond that? “I’d like to be able to take Blood Speaks to the World Economic Forum,” the artist declares.

Poulomi Basu has been nominated for the 2021 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, for her recent photobook titled Centralia (2020). Her work will be on show at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, 25 June – 26 September

From the May 2021 issue of ArtReview