There is a comical discrepancy between the directness of the title of Arthur C. Danto’s new book and the circumbendibus nature of its contents. I am reminded of what a friend recently said about Edna O’Brien’s memoirs Country Girl (2012): “It reads like a distracted dictation, made over her shoulder, as she looks for the sugar in the kitchen cupboard.” But this is far too damning in either case, for meandering and leapfrogs of thought can be deftly orchestrated and pleasurable to follow; but What Art Is is nonetheless oddly categorical for such a friendly excursion as this.

Personally, I enjoy writing that essays, even sashays, through ideas rather than grinding along a prescribed route; and structurally the references and subjects here seem more scenically than strategically navigated. The bookending chapters comprise a more general address of the matter in hand, while the central ones focus on photography, the body and the restoration of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. But besides the lodestar of whim or taste, Kant is taken as a robust guiding reference throughout, religious art is sampled richly, and forays into personal recollections, philosophical texts from Plato to Heidegger and twentieth-century art history underpin an argument that feels both contingent and firm. The resulting view of art is not from the position of every contemporary practitioner, though. In fact Danto makes statements that would rile some I could think of, such as art always being ‘about something’, or most of the art being made today not having ‘the provision of aesthetic experience as its main goal’. And he entirely deskills photography at one point, suggesting that the shutter release might be depressed with the foot just as well as the hand.

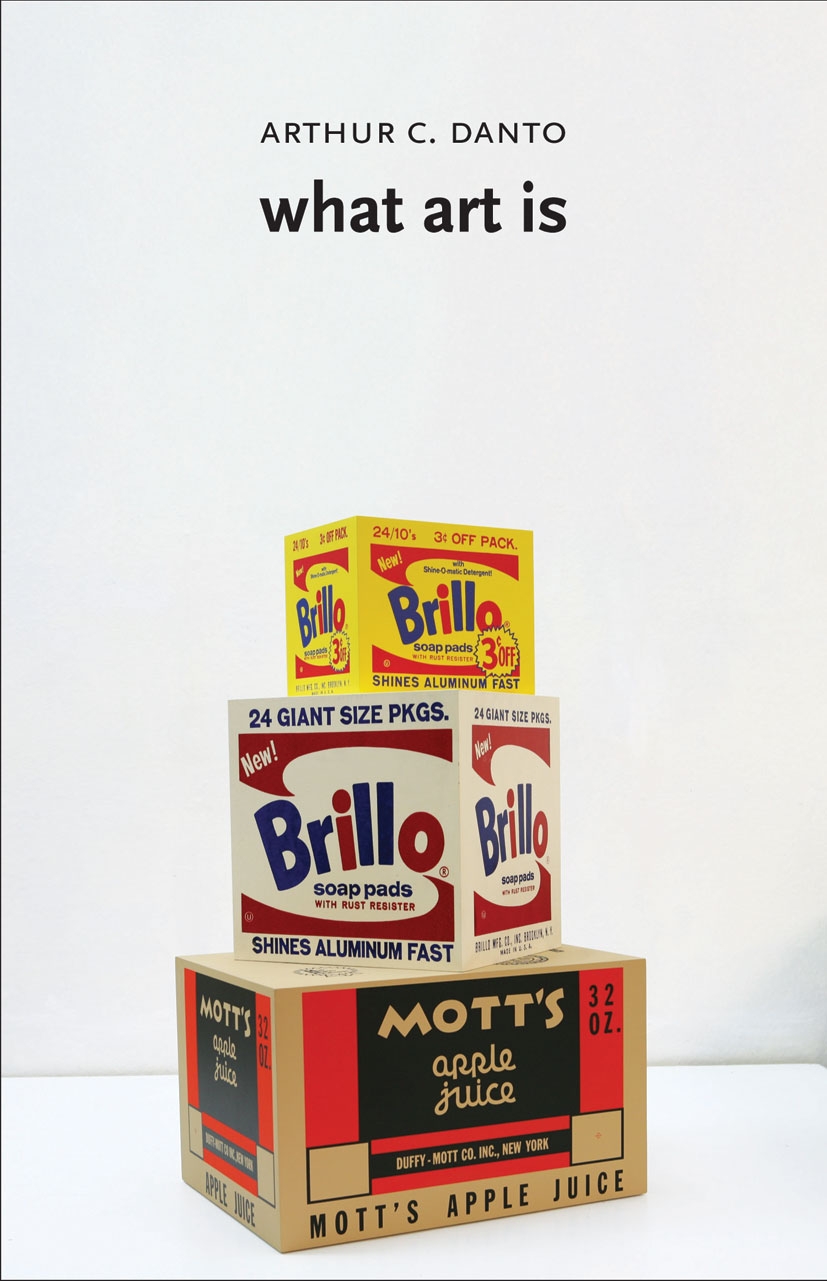

Danto’s toughest debate around the ontology of art is conducted through Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (the first from 1964), but since mid-twentieth- century modes have been so normalised by artists working now, there is a whole new raft of preoccupations that needs addressing. Art’s contestable boundaries with research or activism, for example, go without mention, perhaps because Danto’s consideration is more or less confined to poststructurally inflected objects. But then again, such a pocketable book cannot be expected really to furnish the complete definition of ‘what art is’. Instead, it is primarily a text in which the author demonstrates, thoroughly on his own terms, the proposition that art is not an indefinable category. He vigorously retreads the historical ground that has led some to think that art might be indefinable, through art-historical discontinuities such as Primitivism and Cubism, which upset Albertian modes of representation and ‘visual truth’, and the introduction of readymades, which subverted material expectations. Picasso, Duchamp, Beuys, Rauschenberg, Cage, Warhol – the pivots are familiar, but there is nonetheless an unconventional swing and shuffle with which Danto makes his comparisons and bolsters his points. Indeed, his calling up of references from every which era generates some hilarious anachronistic contiguities, such as the phrase ‘Photographs did not exist in Plato’s time’, and a discussion on the feigned orgasm scene in When Harry Met Sally (1989) in a passage about Danto’s own gallstones, Leibniz’s The Monadology (1714) and the pain of Christ.

But for all its kooky meanderings, What Art Is does provide an incredibly atomised description in the end: ‘The embodiment of ideas or, I would say, of meaning is perhaps all we require as a philosophical theory of what art is.’ The very idea of meaning embodied by a manmade object may seem too teleological or anthropocentric to some, but then Danto is not preoccupied with speculating forwards; rather, he is ruminating backwards, untangling and retangling centuries of thought and production. And rather than marooning us with singularity, he suggests that modes of embodiment vary from work to work. This leaves the interpretative role of the viewer intact, since each embodiment could, in theory, be converted back into meaning; and it is here, presumably, that the illusion of indeterminacy originates.

This article was first published in the May 2013 issue.