What the pioneering 1970 film Samskara tells us as we navigate faultlines of race and caste today

The complex ancestry of America’s new Vice President-elect Kamala Harris straddles multiple faultlines of race and caste. While she identifies as Black, taking on her father’s heritage over her mother’s Indian Tamil Brahmin origins, the way her candidacy and eventual victory was celebrated by Brahmins presents an interesting insight into the caste elites of – specifically – southern India. The Tam-Brams, as the community is called colloquially, are conservative, largely orthodox and thanks to historic access to English education and resulting economic privileges, occupy some of the most powerful positions in society.

The Brahmins as a varna, or caste order were traditionally the priestly class, and as a result, the only section of society that was literate. Their learning of scriptures and the Vedas would make them intermediaries between kings and commoners and the gods. Under colonial rule, it became mutually beneficial for the British and the already literate Brahmins to occupy administrative positions in the public sector. This generational power has long created a vicious circle within which the Brahmins and other upper castes enjoy caste privileges, a perk that they naturally refuse to let go of easily .

Though, from the 1920s onwards, social activist and politician Periyar E. V. Ramasamy’s Self-Respect Movement for social equality in Tamil Nadu made a sizeable dent in the community’s influence on public life, owing to his anti-Brahminism activism (Ramasamy resigned from the ruling Indian National Congress party in 1925 in protest at its perceived discrimination against non-Brahmins), the Tam-Brams continue to enjoy caste privileges that allow them socio-economic mobility. Today, these include easier access to education and a life abroad. The doors such privileges opened would have been one of the reasons Harris’s mother, Shyamala Gopalan Harris, was able to move to the US as a teenager.

While Harris’s success is being celebrated as an achievement for the Brahmin community, the treatment of a less influential figure involved in similar cultural mixing offers an ironic counterpoint. In 2019, the Indian singer and composer – a noted Carnatic vocalist – Sudha Raghunathan and her family were viciously and systematically trolled on social media because of her daughter’s forthcoming marriage to an African-American Christian. Alongside calls for Raghunathan’s concerts to be boycotted or cancelled, the musician was further condemned for failing to uphold Hindu traditions and Brahminism (by ‘allowing’ her daughter to marry outside of race and caste). Notably, the colour of her son-in-law’s skin versus her family’s fair skin tones, and that he was a Christian who would perhaps not allow his future children to be raised in Hindu Brahmin traditions, were major reasons cited for the opposition Raghunathan faced. It must be pointed out here that though Indians were classified internationally as Black until the mid-twentieth century, people of African lineage suffer severe racism in the country even today. Violently suppressing the emancipation of minorities is, of course, not restricted to Tam-Brams, or Brahmins elsewhere, or even the wider plethora of upper castes in India.

This heated mix of identity politics dominating public consciousness, a seemingly endless pandemic, and resurgent debate over race and caste, can be fruitfully examined through the pioneering Indian Kannada-language film Samskara (1970), which marks its 50th anniversary this year. Indeed, revisiting this masterpiece of cinema, made during an age in which feudalism was on the wane and liberal socialists thought that the creation of an equal society was imminent, reveals a greater relevance today even than in the immediate decades following its release.

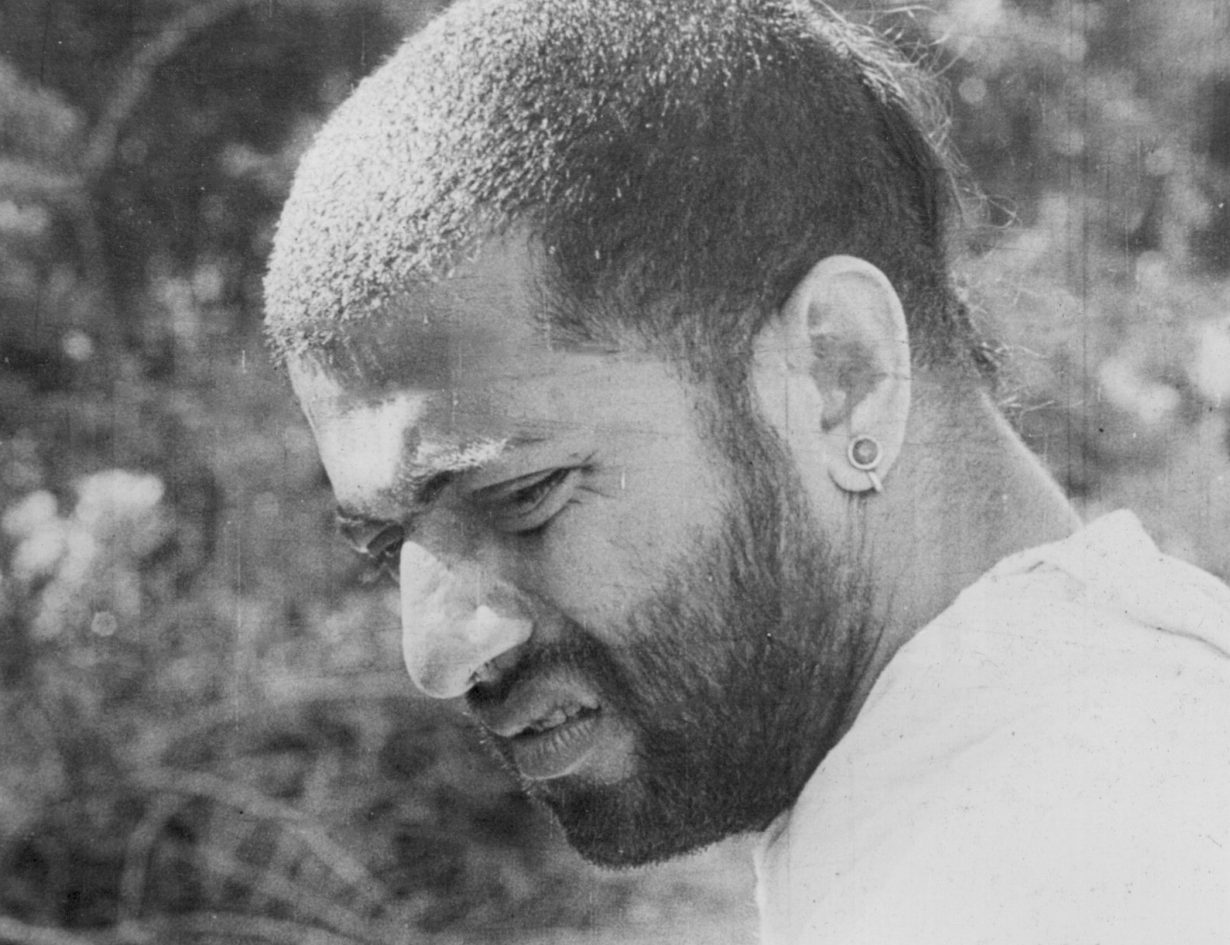

Directed by Pattabhirama Reddy and based on the eponymous 1965 novel by the late Kannada writer, U. R. Ananthamurthy, Samskara – best translated in this instance as ‘a rite for the dead’ – critiqued the frosty orthodoxy of Brahminism and warned of the perils in blindly following its rules. Scripted and played, in the lead role of Praneshacharya, by the late dramatist Girish Karnad, it featured an eclectic cast and crew, not many of whom had previous film experience. Notably, the team was from different castes and communities, with several of them not well-versed in Kannada (a language predominantly spoken in the southwest of India) either.

The plot centres around the agrahara – an area in a village in which only Brahmins live – which is thrown into chaos when Naranappa, a Brahmin who rejects Brahminism’s strictures, dies. He has long rejected his caste, rebelling throughout his life against the fixity and rigidity of the system as a whole by living large, unlike the rest of the agrahara inhabitants whose strictly controlled lives revolve around religious events, abstention, self-denial and hours of daily ritual prayers. Naranappa drinks alcohol, eats meat, and has a low-caste mistress, all forbidden to a twice-born – ‘a male who is “born again” into a life of religion after a coming-of-age ritual’ – Brahmin. When he dies of what is later understood to be bubonic plague, the other Brahmins turn to Praneshacharya, their leader and an archetype of perfect Brahminhood, to decide who is to perform the last rites for Naranappa.

Only another Brahmin can cremate Naranappa’s body. But given that he lived a heretic’s life, the question revolves around who might be willing to sully their caste purity by doing the job. Until the body is cremated, no other Brahmin can have a meal. While Naranappa chose to reject his brahmanatva, his caste ways, brahmanya, Brahminhood did not reject him. Further complicating the situation are a pile of gold ornaments that may be given as a reward to the Brahmin who performs the samskaras, a fast-spreading plague, illicit relationships between some of the younger men and outcaste women, greed, hunger, blind ritualism and the pressure on the perfect Brahmin, Praneshacharya, to save the purity of the agrahara and its Brahmin families. The result is a tragi-comic story that plays with the multiple meanings of the word samskara – as a ritual, as a rite of transformation for Praneshacharya and as a questioning of the spiritual maturity of a community.

Samskara is a work of sociology, a study of micropolitics and an extremely nuanced tale of a community that was losing its validity and importance in the public discourse and societal change of the 1960s and 70s. Revisiting Samskara (2019), a documentary made by the director’s daughter Nandana Reddy, includes a clip in which Ananthamurthy (who died in 2014) describes the project as not so much just a film, ‘but a movement’. Though both the novel and the film had seen their share of controversy for purportedly being anti-Brahmin, Samskara as a work of art was revolutionary in its time. As a novel, it had heralded the Navya (modern) movement in literature and, as a movie, was a pioneering experiment in filmmaking. In the post-Independence Nehruvian India that had turned to socialism in its public policies, this questioning of age-old caste and class orders had seemed like the beginning of major changes in the way modern Indian society would be structured. Today it seems like a movement that has lost much of its momentum.

Such campaigns for societal equality eventually petered out during the course of the decades that followed the film’s release, but never so swiftly as in the last six years of right-wing government rule in India. If racism has undoubtedly become more blatant in the US during Donald Trump’s four years as President, a similar evolution can be traced under the rule of India’s current regime (Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi jointly held back-slapping rallies in both the US and India; a cooling-off only occurring when Modi deemed that Trump was no longer a safe election bet). Like a straight white male being able to thrive on the joint advantages of race, gender and sexual orientation, Brahmins have been able to more openly flaunt their perceived superiority over the mlecchas, the Others. The government’s Hindutva (a form of Hindu nationalism) agenda builds on a myth of Hindu supremacy in a past golden age and seeks to strengthen the caste system. This sits well with the upper castes like Brahmins, and their hopes of maintaining caste and racial purity. As a result, while Brahmins remain a minority in every state in the country, the power, wealth and influence they wield continues to be widely disproportionate to their numbers. A fact that is as true today as it was when the film was being made.

As a result, Samskara has attained a renewed contemporary relevance. Art in its various forms, as literature, as cinema, as critique or as personal identity can question societal orders and invite introspection on a subject about which the mainstream is often silent. The story of Samskara has no easy resolution, and the meaning of the word as a process, as a rite of passage can be read as a possible rite of annihilation for one of the most evil of social systems invented – caste as race, and race as caste.