Jeanne Dielman may be the ‘best film of all time’, but Akerman’s cinema made a commitment to the interminability of the present

2025 marks fifty years since Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, a 198-minute work about a Brussels widow raising her son alone and raising funds by seeing male clients for sex in the afternoons,was first screened at the 28th Cannes film festival. What might its director, the late Chantal Akerman, have made of her narrative feature being voted, in 2022, Sight and Sound’s ‘Best Film of All Time’? It is a compelling thought-experiment. Though she infamously hated lists (when invited to participate in the publication’s 2014 survey she retorted that she didn’t ‘really like the idea. It’s just like at school’) she also, throughout her prolific and astonishingly varied film career, craved mainstream recognition to match her arthouse fame.

Her exuberant foray into romantic comedy, the little-known 1996 film, A Couch in New York, starring Juliette Binoche and William Hurt, was her grab for Hollywood-sized audiences (and budgets). It was both a rebellious volte-face from the academy wanting to cement her as a one-track serious auteur, and a pragmatic, material effort to prove herself as a director and ‘shift tickets’, as she put it in a radio self-portrait broadcast in 2007. Yet even this whimsical – and at the time critically panned – account of an apartment swap between a Parisian dancer and an American psychoanalyst evinced some of the filmmaker’s signature, more sobering motifs: cultural exile, the transient nature of identity, the travails of romantic life. If most commercial cinema aims to allow the spectator to pass, forget or indeed kill time, then Akerman’s filmmaking, as she stated famously throughout her life, wants her audience to feel time in all its physical effects and agonising elongations. Being ‘of all time’ suggests a certain remove from the rhythms and routines of everyday life. Akerman’s cinema is insistently, electrically inside them.

In 1975, Jeanne Dielman was immediately hailed as a feminist core text; a non-sensational portrait of sex work; an unapologetic study of domestic labour invisibly performed by woman on a daily basis and the ‘very first masterpiece of the feminine’ (as Le Monde famously declared). Other critics, such as Jonathan Rosenbaum at the 1975 Edinburgh Film Festival, where the film was screened three times, were baffled by the space the feature cratered in its sparsity of dialogue and denial of psychological intrigue. ‘This one gives me so much freedom that I don’t know what to do with it,’ he wrote.

Akerman herself was wary of Jeanne Dielman being assimilated by feminist film syllabi, or indeed by any over-determined political movement or system. Taking inspiration from the French New Wave and its emphasis on individual artistry modelled by Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, she took pains to state how she was making, above all, ‘Chantal Akerman’s films’. In its choreography of mundane household tasks such as shining shoes and making meatloaf, Jeanne Dielman ushered in a new perceptual regime of filmmaking: one indifferent to the fireworks of ‘plot’ or ‘action’ and attentive instead, to the ordinary grammars of bodies moving in space. Here, Akerman was certainly influenced by the structural, minimalist cinema of Jonas Mekas and Michael Snow which she absorbed in New York City in the early 1970s (where she also worked briefly as a clerk in a porn cinema).

The final sequence – in which Jeanne (indelibly played by Delphine Seyrig) murders a client after reaching unexpected orgasm with him mid-session – was perceived as a ‘transgression’ from the film’s otherwise meticulously realist, almost ‘real-time’ chronicle of one woman’s existence. Yet the film, for all its fastidiousness, is also about what happens when the defences we have built around ourselves begin to splinter. Akerman herself saw Jeanne Dielman as a meditation on the nature of ‘anxiety’; the ‘loss of ritual’; and the lengths that we will go to in order not to have ‘holes’ or too much empty space within our days. Her words hint at what she called the massive hole within her lineage: her mother’s silence with regards to what she endured in the concentration camps (Akerman’s final film was No Home Movie, a plaintive documentary about the last months of her mother Natalia’s life in Belgium after surviving the Holocaust, where both of Akerman’s grandparents were murdered). This context is implicit, and mostly absent from discussions of Jeanne Dielman, yet Akerman’s film is inextricable from this traumatic legacy (‘omnipresent in Akerman’s work from its very beginnings’, as scholar Marion Schmid argues). Even before the first shot – of a woman lighting up a stove to cook – the film sets its opening credits to the insidious hiss of a continuous gas stream.

Akerman wrote, directed and shot Jeanne Dielman with an almost exclusively female crew when she was twenty-five years old. Her feat, in an industry largely inhospitable to women, was the product of her own defiant self-determination and serendipity (Akerman found the blank film to make her earlier film I, You, He, She in an empty corridor while working as a temp) and her fortuitous relationship with the cinematographer Babette Mangolte, who introduced her to a world of artists in New York in the 1970s. The film department of the French Community of Belgium allocated the production of Jeanne Dielman four million Belgian francs. Akerman’s subsequent four decades of inventive (if not always critically or commercially successful) filmmaking intended to shrug off the shackles of that film, as much a triumph as a burden. ‘I’d done what I wanted to do,’ she explained in 2011 to film professor Nicole Brenez, ‘so what to do next?’ A current retrospective of Akerman’s cinema at the BFI Southbank in London explores how the filmmaker began to answer such a question. ‘I wanted to spurn everything – not repeat myself,’ she also said to Brenez, and her challenge to herself not only to make more commercial comedies (Tomorrow We Move, 2004) but literary adaptations (The Captive, 2000); autofiction (Meetings with Anna, 1978); socially incisive documentaries (From the Other Side, 2002; South, 1999) and even musicals (Golden Eighties, 1986), is on full, rigorous display.

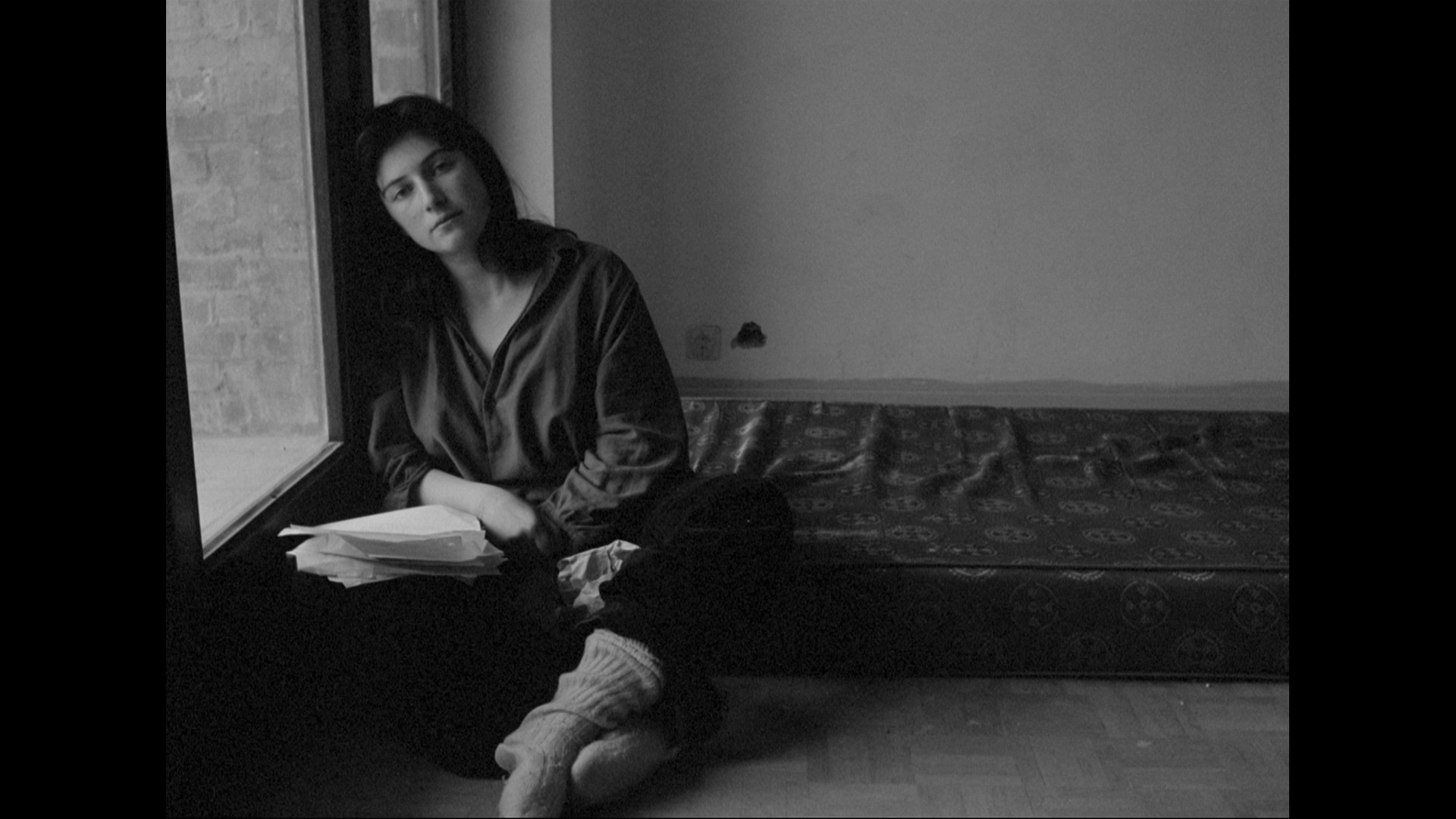

Screening in London are also several films which Akerman produced before the decisive moment of Jeanne Dielman, such as 1974’s languorous I, You, He, She, an ode to the indeterminate, flickering identity of youth, and 1968’s Blow Up My Town, a burlesque Chaplin-inspired portrait of girlish disarray, both of which star Akerman herself as protagonist. Akerman’s under-studied early shorts such as The Beloved Child (1971), 15/8 (1973), and even her accomplished examination pieces made during her short stint at film school in Brussels, also get an airing (and are included in a BFI-produced Blu-Ray boxset). They forecast many of the elements that later crystallise into the iconic ‘Akerman aesthetic’: women in interior spaces; smoking; endless ‘waiting places’, as critic Christine Smallwood notes; and the percussive sound of high heels walking across pavements, another sonic residue of trauma.

A retrospective – much like a crude ranking – can enshrine a legacy too much; cast it in the glossy lacquers of perfection. Akerman resisted such fixity. In her life and work she was unruly, unpredictable and often viciously funny. In a digital exchange conducted in the 2010s via Facebook (of all places), she responded to a fan thanking her for having ‘influenced’ his screenplay. ‘Why so many people told me I had influenced them and I don’t see a penny’, she commented, in her quintessential halting English. This sharp response was more an indictment of a system which refused to fund her more unusual productions (such as Golden Eighties) than of her spectator. ‘It’s time to turn towards the public,’ she wrote. Undoubtedly the prospect of a greater audience – and nakedly, more money – as one probable result of Sight and Sound’s top spot would have gratified Akerman, despite her suspicion of such commemoratives. ‘Who were you influenced by?’ another Facebook user hazards in the same discussion. Akerman posted her reply within one minute. ‘Myself.’

Chantal Akerman: Adventures in Perception is at the BFI until 18 March

Alice Blackhurst is the author of Luxury, Sensation and the Moving Image (2021) and teaches in the French department at the University of Edinburgh