With an apparent appetite for destruction, not least that of his own reputation and even art, what, one might ask, are the Swiss artist’s motivations, and does he have any limits?

Christoph Büchel tends to get cancelled. Take Capital Affair, the Swiss artist’s show with fellow artist Gianni Motti for Zürich’s Helmhaus in 2002: in lieu of artworks, the artists hid a cheque for the total exhibition budget of CHF 50,000 in one of the museum’s galleries. If someone found it, they’d get the money, triggering the show’s closure. If they didn’t, the two artists would claim it on the official closing date, and any damage incurred by the search would be covered by a percentage of the budget and admission fees. The evening prior to the opening, Zürich mayor Elmar Ledergerber requested the amount be reduced to CHF 20,000, otherwise he’d close the show. The artists refused, and Capital Affair was called off two hours before its opening press conference.

Then Büchel’s exhibition at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (Mass MOCA), Training Ground for Democracy, scheduled to open December 2006, collapsed into a lawsuit. Characteristic of Büchel’s brand of institutional critique, where imposing, hyperreal environments confront art’s political claims amid clusterfucked political realities, Training Ground for Democracy intended to mimic the mock-towns constructed by the US military for training, around the time of the ‘surge’, when thousands more US troops were deployed to Iraq. Among the items the museum procured at Büchel’s request were an oil tanker, a smashed police car, deactivated bombshells and a two-storey Cape Cod cottage – but not, alas, a commercial jetliner’s burned-out fuselage. According to court documents, Büchel grew frustrated with the museum’s handling of the project, which included a recreation of Saddam Hussein’s last hiding place. When the museum’s budget reached a limit, impacting assistant wages and prompting the museum to seek support from Büchel’s galleries against his wishes, he refused to continue unless certain conditions were met.

Mass MOCA publicly cancelled Büchel’s show on 22 May 2007 in a press release announcing Made at Mass MOCA, a new exhibition exploring (more successful) largescale artist commissions created at the institution. Büchel’s incomplete work was included albeit covered in tarpaulin, presumably until the museum received a verdict on the lawsuit it filed on 21 May seeking to show its ‘materials and partial constructions’ to the public – ‘the first time a US art institution has ever sought legal sanction to present work against an artist’s will’, noted art historian Virginia Rutledge in 2008. Büchel responded with a number of counterclaims. One sought an injunction on the museum displaying any part of the work, and another claimed damages for violating Büchel’s rights under the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act.

‘Since Mr. Büchel walked off the Mass MOCA project in January, accusations have flown back and forth like poison arrows, and it’s hard to sort out who did or didn’t do what and when,’ wrote Roberta Smith in The New York Times, while taking an unequivocal position on the matter. ‘If an artist who conceived a work says that it is unfinished and should not be exhibited, it isn’t – and shouldn’t be.’ The court felt differently: ‘When an artist makes a decision to begin work on a piece of art and handles the process of creation long-distance via e-mail, using someone else’s property, someone else’s materials, someone else’s money, someone else’s staff, and, to a significant extent, someone else’s suggestions regarding the details of fabrication – with no enforceable written or oral contract defining the parties’ relationship – and that artist becomes unhappy part-way through the project and abandons it,’ wrote the presiding judge, Michael Ponsor, ‘then nothing in the Visual Artists Rights Act or elsewhere in the Copyright Act gives that artist the right to dictate what that “someone else” does with what he has left behind, so long as the remnant is not explicitly labeled as the artist’s work.’

In short, Training Ground for Democracy was a shit show – which in hindsight is unsurprising, given the commission went ahead without a written contract – as was the fallout from its cancellation. Despite its win, Mass MOCA dismantled Training Ground for Democracy, while Büchel reconstituted parts of the installation into Training Ground for Training Ground for Democracy, presented by his then gallery Hauser & Wirth at Art Basel Miami Beach in December 2007. Reflecting the work’s mutation into what Büchel described as an ongoing meta-project, budget spreadsheets, emails, letters and transcripts of legal depositions were shown at Maccarone’s booth in the same fair. ‘This new series of works I have been doing is a kind of physical manifestation of the principle of freedom of speech and expression that the dispute is about,’ Büchel told reporter Randy Kennedy. ‘It says to the museum: You cannot shut me up.’ The irony being that Büchel rarely speaks in public at all.

Meanwhile, Judge Ponsor – whose ruling was partially overturned in 2010 by a federal appeals court – offered ‘a rare personal observation’ of ‘a sad case’ where both parties were responsible. ‘Something barbaric always adheres to the deliberate destruction of a work of art – even one that is not quite finished,’ he wrote, in a statement that could define Büchel’s entire practice. Leaving controversies and cancellations in his wake, Büchel seems to invite that deliberate destruction wherever he goes. There was Deutsche Grammatik at Kassel’s Fridericianum in 2008, where a trade fair of registered German political parties ended up with empty booths after parties represented in the Bundestag cancelled their participation upon learning of the neo-Nazi npd party’s invitation. And THE MOSQUE: The First Mosque in the Historic City of Venice, a working mosque that Büchel controversially installed in a former Catholic church for the Iceland Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, which authorities shut down within a fortnight citing safety concerns.

The litany of offences circles back to one fact: Christoph Büchel tends to get away with things, up to a point. Like when he stacked 1,000 copies of Hitler’s Mein Kampf translated into Arabic in the middle of Hauser & Wirth’s booth at Frieze London in 2006, which received little more than a cheerful mention in a New York Times profile on Iwan Wirth. Or when he opened Guantánamo Initiative, another collaboration with Motti, at Centre Culturel Suisse à Paris at 6pm on 11 September 2004. Challenging the legitimacy of the US naval base and detention centre on the site, Guantánamo Initiative initiated negotiations with the Cuban government to rent Guantánamo Bay and establish a cultural centre there. Documents relating to the 1903 contract that asserted American control over the area were presented, including rent cheques the US Treasury apparently keeps sending to Cuba through the Swiss Embassy, and which the Cuban Government has refused to cash in since the 1959 revolution.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Guantánamo Initiative led nowhere. That is, if the expectation was for the work to achieve its objective rather than agitate for reactions, like those Büchel triggered after launching MAGA, a nonprofit art organisation that petitioned to designate eight prototypes for Donald Trump’s US–Mexico border wall as a national monument in 2018. In an open letter, art workers pointed out ‘the blatant failures of Contemporary Art’ that MAGA highlighted, ‘concerned more with spectacle and irony than critically dismantling oppressive structures that undermine the lives of the most vulnerable’. The co-option of these prototypes – Büchel associated them with Land art and Minimalism – demonstrated contemporary art’s ineffective ‘opposition to power and its abuse’, the letter continued, which ironically aligned with MAGA’s provocation, bearing in mind the CIA’s instrumentalisation of Minimalism and other American art movements during the Cold War. Nevertheless, Büchel’s execution, which amplified his privilege as a white male artist peddling in controversy, obscured that shared concern.

Maybe there’s a point to that. Entangling his apparent loathing of Western imperialism with his contempt for the mainstream artworld and his role within it, Büchel is fine with playing the villain in order to maximise the scope of public discussion around his provocations. Take his two-part 2014 exhibition, Land of David (Poynduk) and Land of David (Southdale Shopping Centre), which installed a prefabricated dwelling used for settlement housing in Israel and Palestine in the Tasmania’s Southwest National Park and transformed Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Tasmania into a shopping centre named after America’s first mall. Exhibits included a mock Australian Liberal Party poster showing white sheep kicking a black sheep off the Australian flag, and one for an oyster bar opening at mona called The Midden, referring to the organic mounds evidencing Aboriginal presence on the site where mona was built. A biography of MONA founder David Walsh contained, among other documents, a list of Israeli illegal settlements, Adolf Eichmann’s Final Solution, a section from Solomon Guggenheim’s biography and reflections on the life of Critchley Parker, who died in 1942 while seeking a homeland in Western Tasmania for Jews escaping the Holocaust, drawing complex links between art, the racist foundations of modern Europe’s nationalist politics, antisemitism and Zionism included, and the settler colonial histories of Australia and Israel.

Land of David opened with scant indication that MONA was staging an exhibition at all, and Büchel’s authorship was only revealed when a stand in MONA’s foyer offering free DNA testing to determine Aboriginal descent – apparently operated by the Australian government, Decode Genetics and Roche – sparked public outcry. (As scholar Eleanor Paynter and writer Nicole Miller have commented, Büchel’s ‘tendency to blur or efface individual authorship reflects an impulse not simply to catalyse audience agency, but to collapse the distinction between aesthetic and social spaces’). Lacking consultation with Tasmania’s Aboriginal community, the installation was accused of being disrespectful and removed.

Describing ‘the spectre of unethical research’ haunting Tasmanian Aboriginal people, historian Greg Lehman contextualised the hurt. ‘The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre was one of the first organisations in Australia to raise concerns when [Human Genome Diversity Project] researchers began collecting DNA from community members,’ Lehman explained in Hobart’s daily newspaper Mercury. Dubbed the Vampire Project, ‘blood samples were obtained without informed consent and the genotypes of individuals were patented, resulting in claims of commercial ownership of the genes of marginalised people by wealthy corporations and governments.’ Nevertheless, Lehman saw a critique of the Vampire Project in Büchel’s installation, given the weaponisation of race, national identity and citizenship in the context of settler colonialism and its state-sanctioned hierarchies of systemic exclusion – ‘issues in 21st century Australia, as they are in the annexation of Palestine by the state of Israel’.

But Büchel’s mona adventure did not stop there. Another part of the project, the C’Mona Community Centre, was a multipurpose space installed in the museum that hosted, among other things, yoga classes, workshops with day-release prisoners and a meeting room for local organisations. Expanding on Büchel’s volunteer-run Piccadilly Community Centre at Hauser & Wirth in London in 2011 – described by art critic Karen Archey as reaching beyond the performative ‘hermetic bubble’ of relational aesthetics and its ‘disingenuous relationship to its subject’, without resolving its contradictions – C’Mona put a complex, unfiltered spotlight on one of modern and contemporary art’s greatest contradictions, by which art is presented as a relational force for the social good by institutions that are intrinsically connected to historical, antirelational structures of exclusionary, hierarchical and extractionist power.

As Lehman noted, ‘much of Tasmania’s economic and cultural industry is built on the dystopic foundations of colonisation’, and the fallout from Büchel’s mona show amplified that fact. Speaking to Australia’s ABC News, Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Chief Executive Heather Sculthorpe said the lack of consultation with Aboriginal elders was nothing new for MONA, making Walsh’s swift decision to remove the work and publicly apologise – after Büchel ‘high-tailed it back to Europe’, per MONA’s Elizabeth Pearce – even more notable. ‘For anyone who is familiar with MONA’s brand, and its posturing as an institution that seeks to shock and challenge, Walsh’s apology drew an unusually ethical line,’ wrote scholar Amy Spiers. ‘Büchel’s strategy succeeded in showing that even mona has its limits.’

But what about Büchel’s limits? Given the volatility of his practice – he’s been called uncooperative, unethical, a ‘shock jock’, a ‘stunning narcissist’, a ‘breaker of budgets’ and ‘a white male artist, continu[ing] the violence of white people’ – Büchel appears to have none, since creating conditions that maximise the potential for reactions that snowball into the public domain produce outcomes even he can’t foresee. Even if Mass MOCA’s then-director Jim Thompson wondered if Büchel’s actions were ‘part of an elaborate art stunt’, Büchel seemed too invested in executing Training Ground to have willed its failure (which doesn’t mean he wasn’t prepared for that potential). Particularly given his thoughts on Capital Affair, whose ‘media-oriented and politico-cultural’ impact was achieved ‘at the cost of the show itself’ and its ‘greater potential for arousing debate’. While reporter Kennedy, reflecting on his exchange with Büchel as his profile rose amid the Mass MOCA scandal, felt that money and attention were secondary concerns.

What remains, then, are Büchel’s motivations. Take his 2017 exhibition at SMAK, Ghent, From the Collection / Verlust der Mitte (Loss of Center). Büchel presented a chronological display of works by artists from the Western canon, from cobra’s Asger Jorn to conceptualist Joseph Beuys, that was shown with mattresses strewn on the floor in the staging of an emergency shelter. Another section of the museum was repurposed into the living quarters for a group of refugees from Syria, Iraq, Somalia and Afghanistan, who participated in an archaeological dig behind the museum – ostensibly in cooperation with Association Internationale Africaine, tied to the Belgian King Leopold II’s murderous colonisation of the Congo – looking for traces of a citadel on which a casino was built for Ghent’s 1913 World Expo, which eventually became SMAK. The refugees also rebuilt sections of the Calais ‘Jungle’ refugee camp on a site near the museum where a human zoo as Senegalese village was installed for that 1913 Expo. That gesture circled back to Büchel’s show, which included a replica of the Congolese village presented at the 1958 World Expo in Brussels, and a trade-fair display of promotional materials by companies invested in Africa, like SDA/SDAI, which bankrolled the renovation of Belgium’s Royal Museum of Central Africa.

Writing in Metropolis M, Ghent-based critic Ory Dessau described Loss of Center as ‘more than a gesture of institutional critique deconstructing the ideology of the white cube and of museal display’, because ‘it politicizes the artistic and cultural heritage of SMAK, and consequently of Modernism in general, situating them within and exposing them to the bleeding context of the current European refugee crisis and its historical roots in European colonialism’. Yet, as Gareth Harris noted in The Art Newspaper, while the project drew attention to the Mediterranean migrant crisis, it largely ‘remained under the radar’. Which may explain Büchel’s decision to transport the boat in which hundreds of migrants died in 2015 to the Venice Biennale in 2019, calling it Barca Nostra – ‘Our Boat’ – and installing it in front of a café at the Arsenale.

Essentially a horrific readymade, Barca Nostra sunk in April 2015 between Libya and Lampedusa with an estimated 1,000 migrants onboard, of whom 28 survived. The Italian government recovered the wreck in 2016 and moved it to a base in Sicily before it was placed under the care of the Augusta municipality, a landing site for Operation Mare Nostrum, Italy’s response to the Mediterranean migrant crisis. Mare Nostrum, or ‘Our Sea’, cost the Italian government a reported £7 million per month, and ensured safe passage for over 100,000 people within a year of its launch in October 2013. But after Italy appealed for assistance, EU states criticised the operation for encouraging people to risk the sea crossing, so EU agency Frontex replaced Mare Nostrum with Operation Triton in 2014, with a slashed budget and focus on border security.

Effectively a policy of nonassistance, as Forensic Oceanography concluded in their 2016 report Death by Rescue: The Lethal Effects of Non-Assistance at Sea, Triton created a situation where commercial ships were increasingly called into rescue missions they weren’t suited to conduct – such was the case with the sinking of Barca Nostra in 2015, they found. That year, European Parliament president Martin Schulz called for ‘burden sharing’ based on the fact that five out of 28 EU member states were taking in 50 percent of refugees to Europe at the time. Yet no effective cooperation manifested. Neither in creating humanitarian responses to a global crisis, nor in mediating the ultraright sentiments and movements that rose as a result – as demonstrated in 2018, when Italy’s far-right interior minister, Matteo Salvini, launched a campaign to block search-and-rescue vessels from docking in Italian ports, and drafted a hardline anti-migrant bill adopted by the Italian government.

It was within this desperate context that Barca Nostra was brought to the Venice Biennale – in cooperation with Augusta’s municipal council and Comitato 18 Aprile, which lobbied against government plans to scrap the ship – with Büchel covering transportation costs. Presented with little information – not for the lulz, it seems, but out of contempt for a wilful ignorance – the vessel’s arrival was lambasted as ‘tasteless’ by those at the vernissage, seemingly more concerned with the insult of its presence – and those taking selfies with it, like a Martha Rosler collage come to life – than discussing the exclusionary policies that brought it into being. (Granted, as curator Alexandra Stock wrote in a scathing takedown, ‘The optics [were] bad because Büchel set it up that way’.) While the stunt drew international attention – including responses from Salvini himself, countering the idea that the Venice Biennale is an ineffective stage for protest – it also revealed the limits of internationalism, whether in the artworld or the world at large.

That limit has been monumentalised by the trail of articles and posts that exist as a result, like a fraught and ever-expanding shadow of an ongoing crime; whether a petition for the boat’s removal from the Venice Biennale accusing Büchel of capitalising on Black death to news reports tracking the boat’s delayed return to Augusta years later, where plans are afoot to create a memorial garden around it. ‘Certainly, the ship has attained an international dimension,’ Augusta mayor Giuseppe Di Mare told The Art Newspaper in 2021, summing up the motivations behind Barca Nostra from the outset, with the vessel’s delayed return to Sicily extending that range. Attributed to the damage incurred during its transportation to Venice, when its metal cradle collapsed while being lifted by a crane, Büchel made a claim through the Biennale’s insurance to repair the vessel for its return, but was denied since the damage occurred in the air and not in the sea – a predictably sophistic avoidance of responsibility.

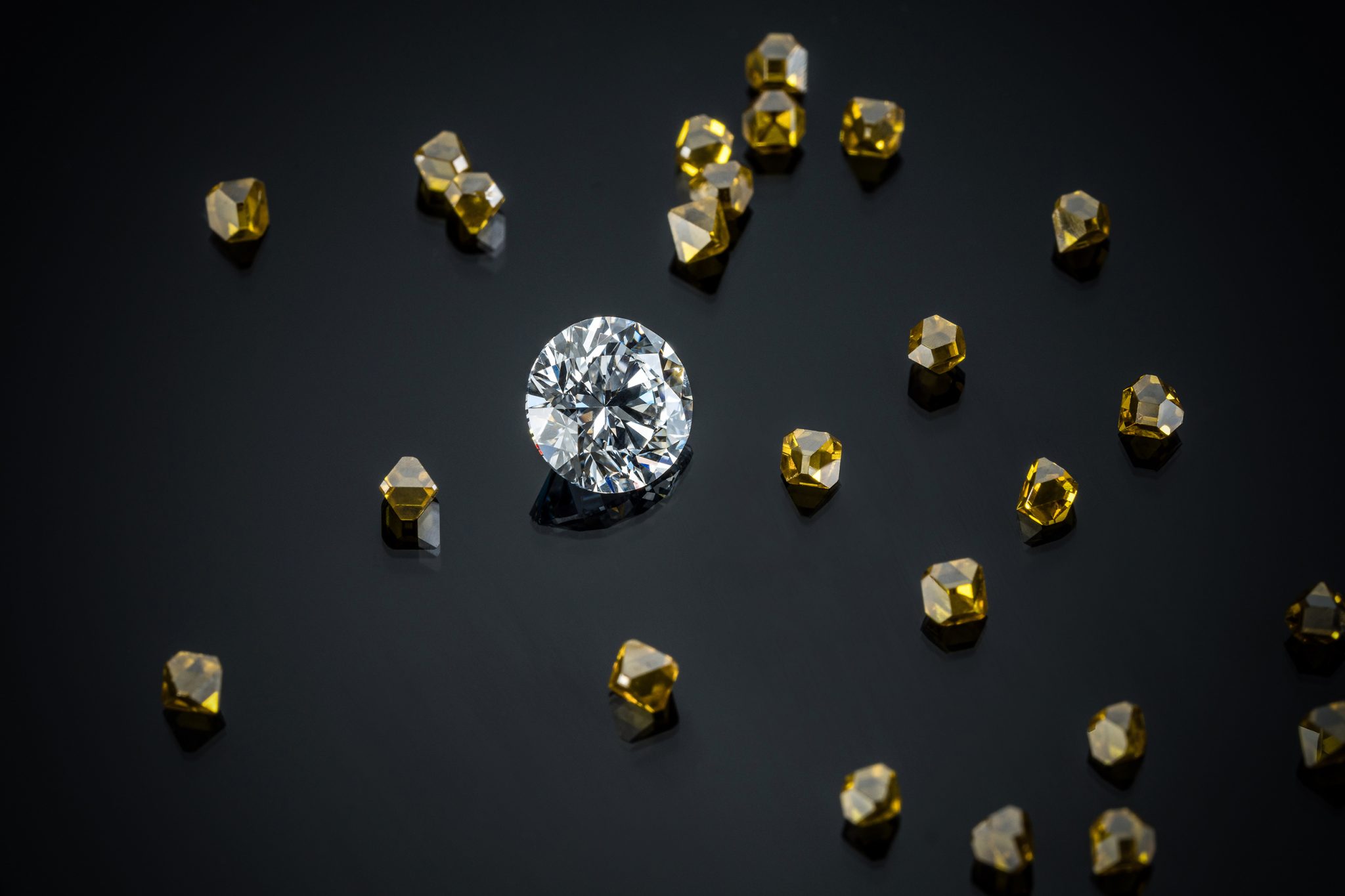

Given the financial burden Büchel presumably shouldered, perhaps it’s no surprise that the subject of his latest project, with Fondazione Prada at the Ca’ Corner della Regina in Venice, is debt. The artist’s installation, Monte di Pietà, engages with the history of an eighteenth-century palazzo that served as a charitable pawn bank from 1834 to 1969, before it became the Historical Archive of the Venice Biennale between 1975 and 2010. A central element to the exhibition is The Diamond Maker: lab-grown single-carat diamonds that Büchel has been making since 2020, using his unsold works and DNA from his own faeces, with the intention to continue until he dies. There’s some poetry to the gesture, with each shit-diamond appearing like a tearful, if disdainful, lament: as much a ploy to stay financially afloat, maybe, as an expression of an ageing artist’s outlook on an artworld he seems incapable of coming to terms with – even if there seem to be plenty in that world still willing to support him.

There are echoes of 1% in this monetary return. Presented at Frieze New York in 2012, the year he sought funds to bury a Boeing 727 in the desert, 1% was Büchel’s attempt to sell six trolleys bought from homeless people for between $350 and $500 for 100 times more. The only Q&A with the artist that exists online could explain why he relies on such dick moves, which tar what may well be decent intentions with a shitty brush. ‘When money is used as the content and theme of a show, you’ve got to expect people to react. But there’s no telling how they will react,’ he said of Capital Affair. ‘No direct provocation or umpteenth art scandal was intended. It was meant more in the sense of a catalyst for debate, something which crowd-pleasing shows rarely achieve.’ Cue Ponsor’s observation of a barbaric residue that sticks to an artwork that is deliberately destroyed. Only now, the piece of work is Büchel himself.

Christoph Büchel’s exhibition Monte di Pietà is on view at Fondazione Prada, Ca’ Corner della Regina, Venice, 20 April – 24 November

Stephanie Bailey is a writer and editor based in Hong Kong