The theatre director, filmmaker and performance artist, who died in 2010, made art that played with public opinion to expose unacknowledged truths

‘Aesthetics is also a theory and praxis of life. But it doesn’t understand life teleologically or functionally… The aesthetic motions and variations of the living body are expressions of an inner principle, a force, but they do not fulfil any function. They are not executed to realise a purpose or to fulfil a function, but unfold without any orientation or direction.’

Christoph Menke, Am Tag der Krise (On the Day of the Crisis), 2018

In his 1794 epistolary work On the Aesthetic Education of Man, Friedrich Schiller claims that art is characterised by its emancipation ‘from all that is named constraint, whether physical or moral’. That emancipation applies only in the aesthetic ‘realm of play and appearance’ and not, of course, to everyday life. In other words, according to Schiller, art is allowed to do anything as long as it is purposeless; when it is used to conceal tangible interests and strategies, it leaves the realm of art and loses all of its privileges. The reality of art, then, is precisely its unreality. This leads to a dilemma that affects every engaged art practice: either it is ineffective; or it is subject to the socioeconomic rules that govern everyday life.

Of course there are artists (no doubt many) who do not accept the distinction – that art is either condemned to ineffectiveness or surrenders its freedom. They not only want to play within the confines of the segregated space reserved for art, but also to test its boundaries. And it’s easy to come to the conclusion that art is only interesting when artists do just that. More than two decades ago, and in contrast to many recent attempts to make art and theatre become an effective part of society, Christoph Schlingensief ’s action art explored that territory by allowing artistic freedom to be played out in the social sphere.

Schlingensief, who died in 2010, did not subordinate aesthetic freedom to the functional systems of society at large; instead he used it to permeate the boundaries of those systems, thereby generating a different type of vitality. Schlingensief’s art was always a game played with limits and their potential transgression. Naturally, this was at its most dangerous when it came to actions in public space. For only a small part of this environment can be controlled by a director: spatiotemporal aesthetics and everyday life, art and non-art, mingle in unpredictable ways. It was this play with unknown and uncontrollable elements that most interested Schlingensief: the unplanned side-effects of his interventions became essential. And his most radical action, in terms of form and content, which took place in 2000 under the framework of the Wiener Festwochen, makes this especially clear.

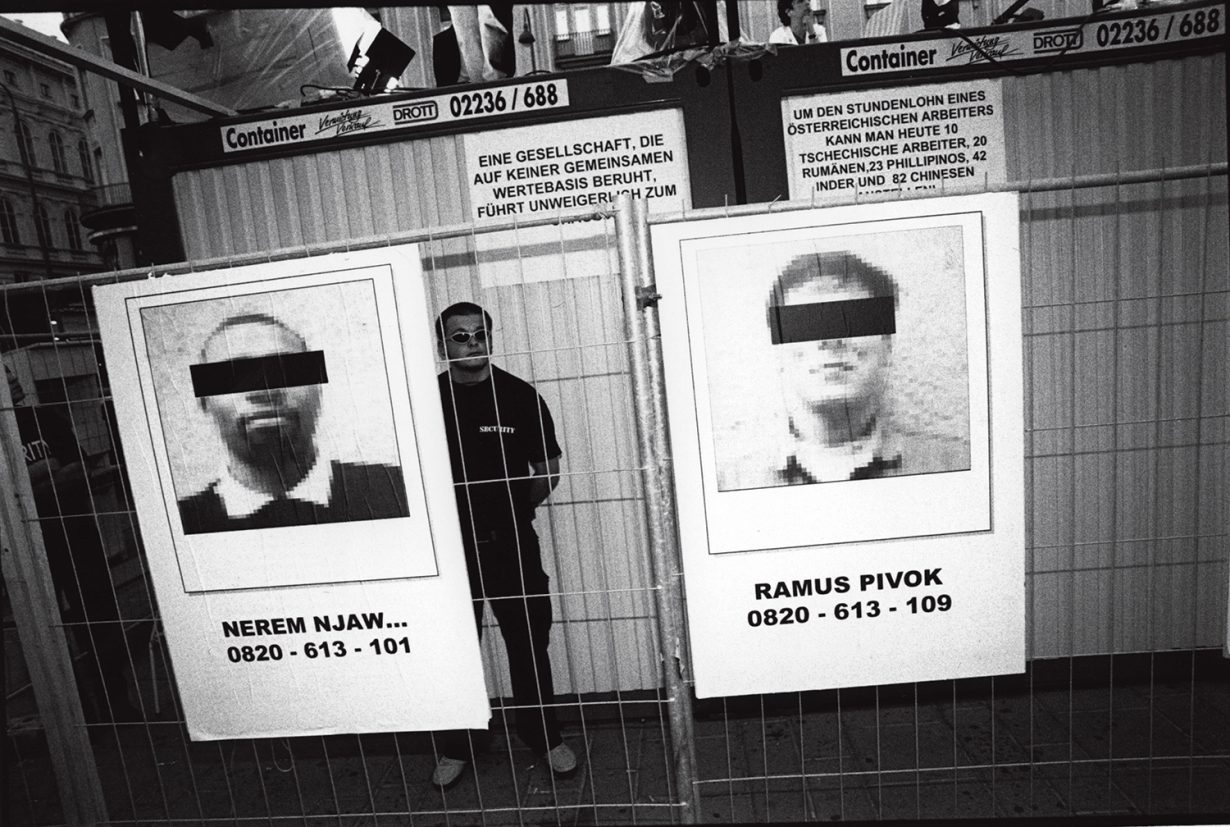

The action took place on Herbert-von-Karajan-Platz next to the Wiener Staatsoper in the middle of Vienna’s historic city centre. There, containers were set up (with official approval) to accommodate asylum seekers who could be selected by the general public, via phone or the Internet, to be evicted (a nod to the popular TV show Big Brother, which debuted in Holland a year prior). The survivor would win the right to stay in Austria, gaining citizenship by way of marriage. The outcasts would be deported.

The work followed Schlingensief’s public calls in the name of art (in Germany, freedom of expression in the arts is protected under the constitution) for the killing of politicians (among them then German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, at Documenta in Kassel in 1997; in 2000, then Austrian Chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel, shortly before the Vienna action; and in 2002, Jürgen Möllemann, Kohl’s vice chancellor) and was a response to the swing to the right in Austrian politics. (The October 1999 parliamentary elections had ushered in the first ÖVP/FPÖ coalition government – the ÖVP is a conservative Christian Democratic Party that has been a part of most of Austria’s governments in the postwar era; the FPÖ is a far-right populist party originally led by former Nazis, among them SS officers – and made racism and xenophobia once again acceptable in Austria.) Originally titled Tötet Europa! (Kill Europe!), it was later, at the request of the festival director, Luc Bondy, given the more friendly title Bitte liebt Österreich! (Please Love Austria!).

At the opening of this sarcastic performance, a large banner reading ‘Foreigners Out’ was unveiled above the container containing the candidates, to the applause and jubilation of art and theatre fans attending the event. And so, people who would never identify or be identified as rightwing extremists cheered the unveiling of a clearly xenophobic statement. Or did they cheer the erection of a banner that clearly portrayed Austria, to outsiders at least, in a very bad light? The action as a whole lived on such ambiguous or opaque processes.

Unlike Schlingensief ’s earlier works, which largely deployed ‘positive’ forms of expression, here, the copying and appropriation of right-wing stereotypes took place for an extended period of time. For clarity’s sake, the organisers of the Wiener Festwochen initially attached a sign to the container declaring the whole thing to be an antifascist art event in the context of the festival. This was removed however at the behest of Schlingensief (who, incidentally, had also refused to use art as an explicit defence when he was arrested at Documenta for his banner demanding the death of Helmut Kohl). Instead, the action sat on the edge of reality, mixing real asylum seekers (equipped with fake biographies) with actors playing the role of asylum seekers; real politicians (such as Daniel Cohn-Bendit) with artists (among them musicians such as Einstürzende Neubauten, writers such as Elfriede Jelinek) and unsuspecting passersby; even a Schlingensief lookalike, through whom the real Schlingensief could push tasteless utterances and politically incorrect statements that had been attributed to him. No one involved, friend or foe, had any idea how the action would develop. And neither did Schlingensief himself.

He, for example, suspected that the ‘Foreigners Out’ sign would be destroyed by rightwingers, insulted by such a direct expression of one of their goals, but it was leftwing protesters, participants in the ‘Thursday demonstrations’ against the conservative-fascist government, who stormed the container village and tore down the banner, thus saving their political opponents (who had tried to use legal means to have the banner removed) the bother, and removing a highly visible blemish on Austria’s good name. All of which completely contradicted the political intentions of those on the left.

The week of action against xenophobia was nerve-wracking for everyone involved. Communicating the social and asocial life of art without seriously jeopardising the one or the other required the utmost discipline. In spite of everything, the whole thing remained an art event, an aesthetic practice that, as opposed to social practice, understands ‘life as neither functional nor teleological’ (as philosopher Christoph Menke would put it). And everyone joined in the game, even politicians and the press, whether they wanted to or not. It’s also worth noting that none of the legal actions against the project were successful; the action wasn’t forcibly shut down, nor was it interfered with by the police or other security services. Here, amid the general public, in a place far removed from art’s usual confines, Schiller’s ‘joyous third realm of art’ was able to unfold, although its boundaries were often pierced in violent and threatening ways. Perhaps the deciding factor in this game-changing aesthetic action was that for seven days and nights it created an in-between world that couldn’t exist anywhere except in a work that simultaneously adhered to and transcended the boundaries of art. The action may not have actually helped a single asylum seeker, but it held up a mirror to the reasonable, abyssal and obsessional thoughts of a society and demonstrated that the world is more than simply a means to an end.

In many of today’s attempts to break free from the limits of art and make work that is effective in the public realm, aesthetic freedom, the thing that is specific to art, has fallen by the wayside. Artists submit to the constraints of circumstance. They no longer legitimise their art aesthetically, but morally, politically or economically. They say they have entered society and left their ivory tower behind, but they have also abandoned art to make it a mere means to an end. And that is why, for many of them, artistic freedom no longer seems such a relevant topic.

The only difference now is between art that has a monetary value and art that has a use value. The heterotopic art that Schlingensief stood for is simply no longer there. If it is, it is viewed with suspicion, and when there are doubts about it, it is constrained, removed and sometimes even forbidden. This might be done without any malicious intent on the basis of the extra-aesthetic criteria to which art submits.

The following might provide an example of this. Last August, as part of the biennale titled Bad News and organised by the Staatstheater Wiesbaden, a four-metre-high gilt statue of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was placed in a public square in the German city. It triggered unrest and uncertainty among the friends and enemies of this new type of strongman, and among Wiesbaden’s citizens in general. As is the case with good works of art, this one could not be clearly defined. It illustrated no clear (political) conviction and was highly ambivalent in its pathos. It was both too pompous and ridiculous to be a tribute and yet was not enough of a caricature to be a warning. There was no ‘instruction manual’ that told the viewer how to interpret the work, which had been installed overnight. During the next 24 hours, the work caused a stir and open debate among observers, some of whom had very different ideas – both of Erdoğan and of the statue in front of which they stood. Although city leaders initially expressed their solidarity with artistic freedom, the local fire brigade was brought in to dismantle the work 26 hours after its unveiling, without any prior consultation with the festival organisers. It was suggested that public debate about the work might escalate to the point at which people’s safety could no longer be guaranteed. However, the evidence to support these allegations was thin, and the assertion that ‘knives were spotted’ near the artwork was swiftly withdrawn. Similarly, the assumption that Erdoğan-hating Kurds from all over Germany were on their way to Wiesbaden to destroy the golden statue proved groundless. The notion mooted by the festival organisers that even a work of art should be protected – just as are politicians, sportspeople, demonstrators and transports of hazardous materials – by the police if necessary, was barely commented on by politicians and ridiculed by sections of the press.

The fact that the justifications given for the rapid removal of the artwork were disparate and proved groundless under scrutiny was glossed over with astonishing indifference by both the press and the public. Even in the German art magazine Monopol, for whom a defence of the freedom of art should be fundamental, one finds an attitude that seems to be censor-friendly: ‘Anyone who wants to use art to provoke a society that is in a constant state of agitation has more responsibility than ever before. We really do not need a golden dictator from an artist who remains anonymous, does not take part in debate and does not moderate the dispute.’ The artist’s refusal to speak publicly about their work and to moderate on its behalf so that everyone can understand it and read its embedded social meaning apparently legitimises the intervention of the authorities. With his non-self-explanatory art, or art that did not announce itself as art, Schlingensief would have no chance. For many people a general fear of open or public dispute makes this kind of censorship not simply acceptable, but desirable. And the fact that art might provide an outlet for the transcendence of such conflicts is not considered at all.

Among some art lovers and art magazine editors, this happens so as not to play into the hands of an already polarised ‘populist society’ and the certainly well-intentioned desire not to allow irresponsible artists to weaken an internally and externally endangered democracy. Similar allegations were made almost 20 years ago against Schlingensief. There were, of course, demands in Vienna that Bitte liebt Österreich! be banned, but unlike in Wiesbaden the project was able to run until its planned end because, despite the scepticism and criticism, the Wiener Festwochen and the cultural authorities were behind Schlingensief and his fellow campaigners. Certainly this had something to do with the fact that Schlingensief himself was present all the time, putting his head above the parapet and taking responsibility for the confusion he was causing. Moreover, he did this with both charisma and humour – qualities to which the increasing instrumentalisation of art for moral and political purposes may not be conducive. Moreover, it seems to have been forgotten that aesthetic practice, by definition, does not have to comply with the letter of the law, and because it does not, art is often disturbing and unsettling, and not a matter of consensus. But at exactly this point it needs special protection. Art that pleases everyone is always ‘free’, even under the worst dictatorship.

On the subject of dictatorship, in a recent publication on contem- porary theatre in China, I read: ‘In the People’s Republic of China there is no public performance without state authorisation, the criteria for which remains vague, which in turn constitutes the essence of censor- ship.’ This obviously describes a local phenomenon, but the restriction and prohibition of art by means of sacrosanct and inscrutable admin- istrative acts happens here too. For someone who thinks that the prac- tice of art as a form of aesthetics is marginal and antiquated, that might not be so bad. But those who have even a little understanding of the histories of democracy and totalitarianism know what a curtailment of aesthetic freedom means. If, in times of internal and external threats to democracy, the crisis is dealt with by the instrumentalisation, margin- alisation and control of art, as well as by vague ‘censorshiplike’ measures, what we are faced with is, at the very least, a fatal case of historical amnesia.

Carl Hegemann is a writer and dramaturge who collaborated with Schlingensief.

Translated from the German by Mark Rappolt.