To frame her work under the catch-all terms of humanist representation is to flatten it, as well as to deny the material realities of its production

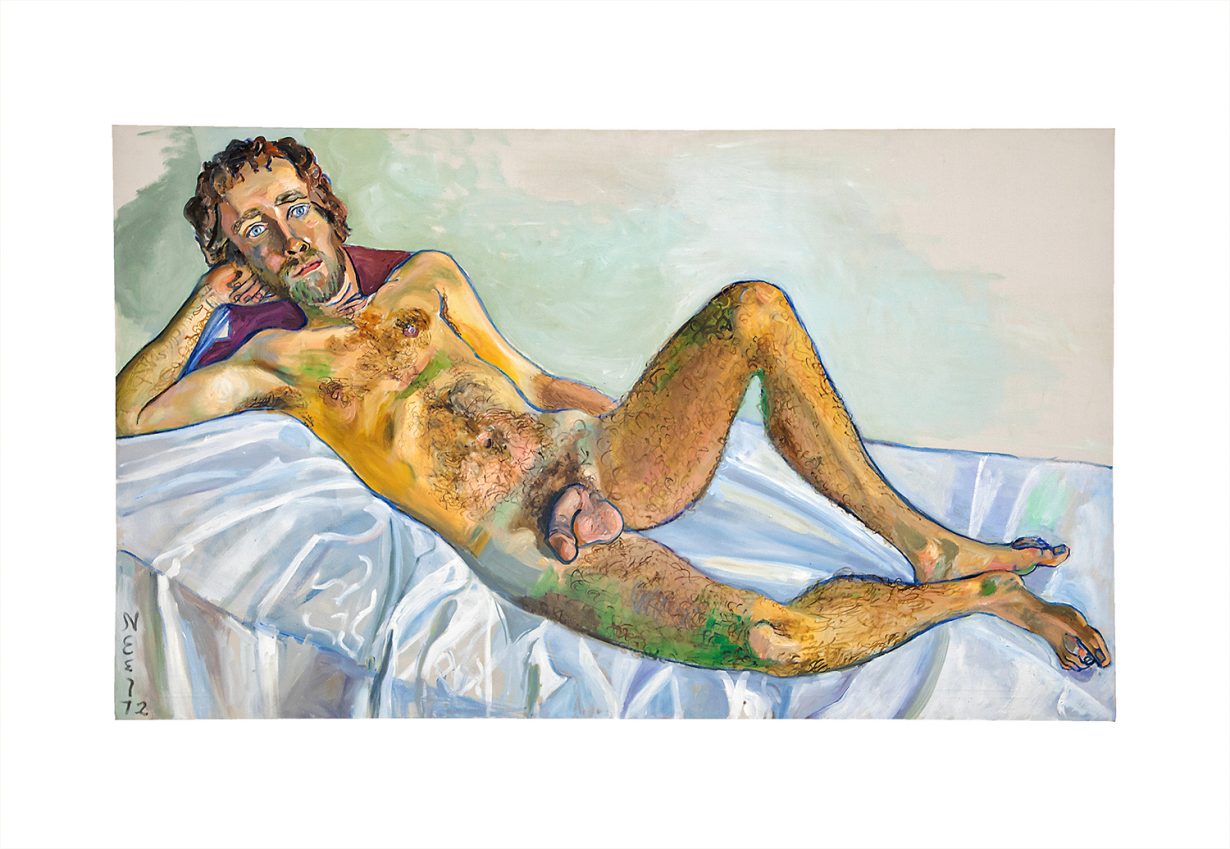

In Alice Neel’s 1951 painting The Death of Mother Bloor, the corpse lies – as if beatified – in an open casket and surrounded by flowers. A crowd of mourners include, at the very front, a woman cradling a baby in her arms. To the left of this baby, on a bank of red and pink roses, luscious and so alive, a banner is unfurled; it reads ‘COMMUNIST PARTY’. Ella Reeve Bloor was one of the founders of the Communist Labor Party of America, a predecessor of the Communist Party of the USA, and a tireless labour organiser during the Great Depression. While Bloor was working with the United Farmers League and participating in actions like the Ambridge steel strike, Neel was engaged in documenting ‘the American scene’ for the Public Works of Art Project, one of Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives. Neel, like Bloor, was committed to the Party, which she joined in 1935 and remained affiliated with until her death: in 1981, she became the first living artist to have a retrospective in the Soviet Union, and in an interview in 1983 she declared that ‘the whole 20th century has been a struggle between communism and capitalism’. (The critic John Perreault, who sat nude for her in 1972, described Neel in 2007 as a ‘jolly Stalinist to the end’).

Alice Neel

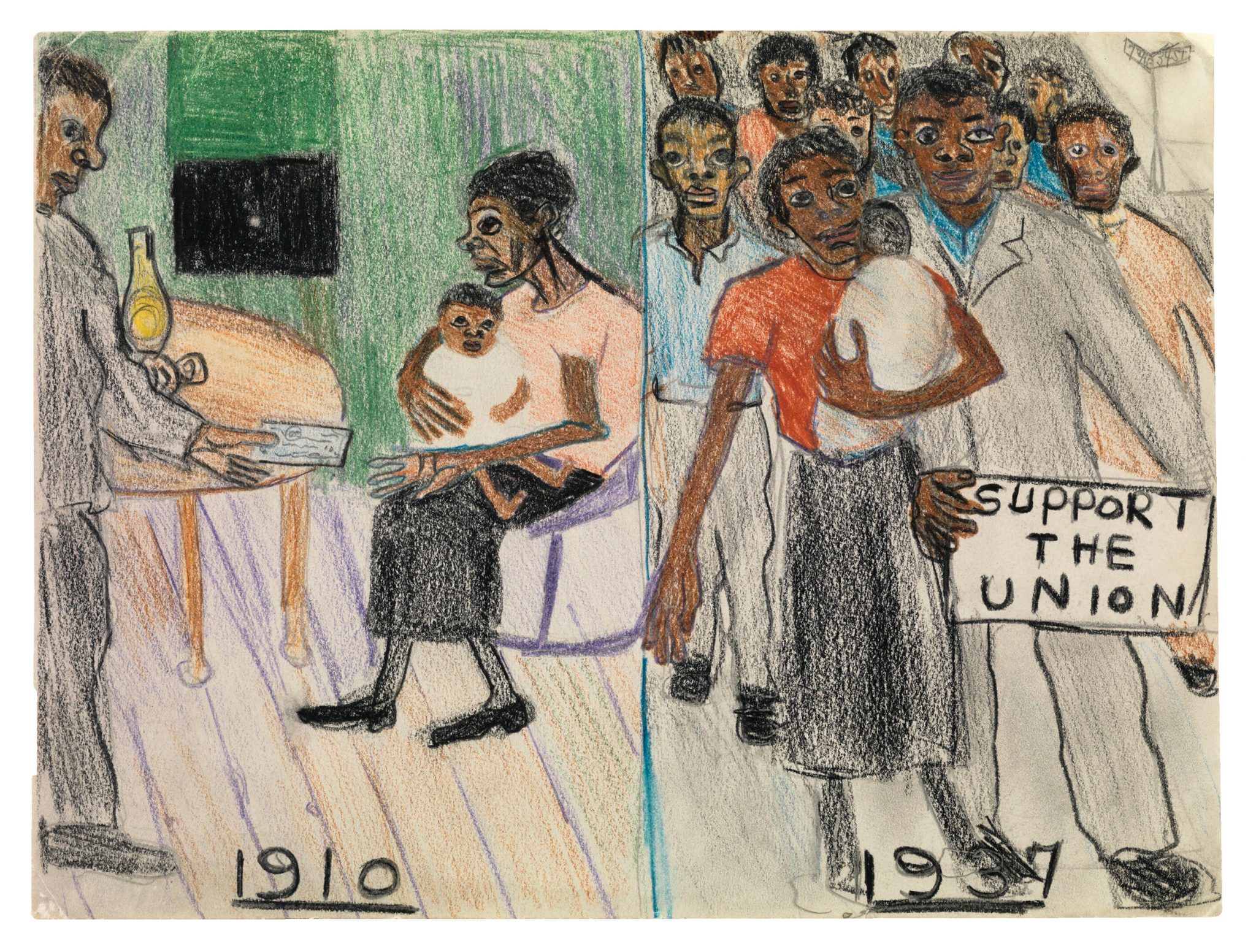

Babies are everywhere in Neel’s paintings, 70 of which are now showing in Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle at the Barbican Art Gallery in London. Images of breastfeeding, handholding, cradling and exhaustion proliferate in, amongst others, Spanish mother and Child (1942), Mother and Child (1962), and Carmen and Judy (1972). There is a baby cradled by a protester in Support the Union (1937) and babies held protectively at the edge of the police violence unfolding in Uneeda Biscuit Strike (1936). And there are the pregnant people, too, often naked, their enormous bellies swollen with life: in Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978), the viewer, met by a gaze that seems to be able to see the future, can’t look away.

Communism was, as the saying went, ‘the youth of the world’. This was especially relevant to the CPUSA, which had a membership primarily composed of families, linked together by youth groups, summer camps and red Sunday schools. Vivian Gornick, in her 1977 oral history The Romance of American Communism declared that, growing up in a community of Jewish party members in the Bronx in the 1930s and ’40s, ‘before I knew that I was Jewish or a girl, I knew that I was a member of the working class’: solidarity was imparted at your mother’s knee. Neel was a generation or so older than Gornick, but both women were deeply embedded in the Party and the unaffiliated Marxist movements that came after it – and so their respective works present similar kinds of social portraiture, one in paper and ink and one in oil and canvas.

Alice Neel

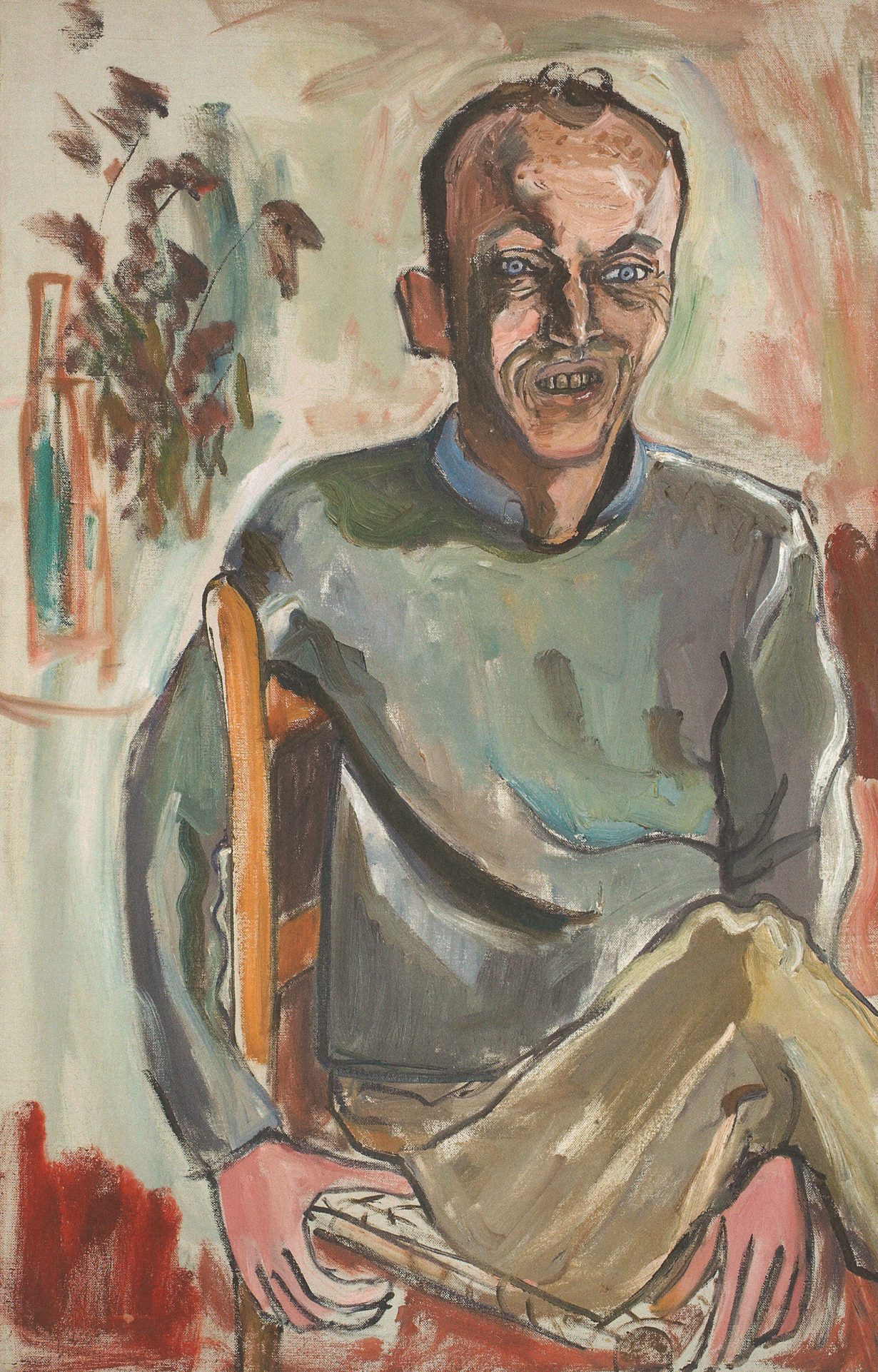

‘Portraiture,’ this exhibition makes clear, is a term that Neel hated, perhaps because of its too-neat categorisation: in Nancy Baer’s 1978 documentary about her, Collector of Souls, which plays in the exhibition’s penultimate room, we hear her resisting it. Still, her figurative paintings embody her belief that abstraction was a ‘distraction’ from what really mattered: people. It’s important not to regard this interest in individual bodies and faces as a disinterest in collective political life. In her own words, Neel sought to identify in her subjects, who range from the very famous (Andy Warhol) to the celebrated but less famous (CPUSA chair Gus Hall) to the decidedly unfamous, ‘what the world has done to them, and their retaliation’: she depicts societal structures in the lines around their eyes and the shape of their hands. Above all, she understood each image to be equally weighted: we are all bodies in history.

Neel, whose late-in-life professional success can be attributed in part to the feminist movement of the 1970s (her work was included in the landmark exhibition Women Artists, 1550-1950, curated by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1976), is easy to frame through the popular lens of feminist recovery and rediscovery. It’s harder, it seems, to centre her communism. The art historian Gerald Meyer observed in 2009 that, although Neel’s politics informed her choices – ‘where she lived, her life partners, what she read’ – and, crucially, ‘determined her subjects and her aesthetics’, her explicit commitment to communism is frequently underplayed, even erased, in contemporary accounts of her work.

Alice Neel

Both the Barbican exhibition itself and critical responses to it have preferred to focus on Neel as a ‘humanist’. The quotes in large letters on the wall – ‘I’m not against abstraction’, begins one; ‘All my life I wanted to do a nude portrait’ begins another – skew the focus towards a generic, digestible manifesto. When her communism is unavoidable, it is played for laughs: the poster of Lenin she kept on the wall until she died is mentioned as merely an eccentricity, the home visit from FBI agents in 1955 simply an excuse to tell the story of how she tried to persuade them to sit for her and quote, approvingly, the description of her as ‘a romantic, Bohemian-type communist’ which came from an informant. The exhibition’s curator Eleanor Nairne urged in a recent interview that, rather than discuss Neel’s politics in a ‘capital P way’, we should instead consider a ‘softer but just as powerful vision of the politics of her painting, which is about what it means to see another person for who they are’. The art historian Katy Hessel describes her work as ‘timeless’, continuing that Neel didn’t ‘discriminate’ between subjects: ‘Representation can be so powerful’.

Representation of what? Hilton Als, who curated an exhibition of Neel’s work in New York in 2017, wrote that, for Neel, ‘the first mark of being political was looking: seeing what was done to others in this world, and how the afflicted became afflicted, or what nowadays we might call the disenfranchised’. Her work does not – cannot – separate the effects of such disenfranchisement from the mechanisms which cause it. She practised solidarity rather than empathy: active in organising with the Artists’ Union, she lived on welfare for most of her life, and amongst the community she painted: in Als’s words, ‘Neel’s soul saw itself in East Harlem, where struggle contributed to the making of faces, along with goodness, while all that life shambled through the streets’. To frame her work under the catch-all terms of humanist representation is to flatten it, as well as to deny the material realities of its production.

Alice Neel

Solidarity isn’t simple, and it is not synonymous with celebration. Neel often said that she would have been a psychiatrist if she hadn’t become a painter, making an explicit link between painting and psychic excavation. Yet such attention is not always easy for the artist’s subject to bear. Neel was, in Perreault’s words, a ‘merciless realist’ (he calls himself her ‘nude victim’), and part of the brilliance of her work is its unsettling capacity for revelation: we see more, in these people, than they might wish us to. Frank O’Hara leers out with stained teeth from Frank O’Hara No. 2 (1960); Linda Nochlin and her daughter Daisy sit in a tense, unbalanced dyad – Daisy illuminated and Nochlin’s face greenish and exhausted in Linda Nochlin and Daisy (1973); John Rothschild’s naked body in both Alienation and Untitled (both 1935) is made faintly ridiculous by the little slippers he is wearing, in contrast with Neel’s confidence in her own nudity.

Alice Neel.

In suggesting that the position of the painter was aligned with the position of the therapist, Neel is inverting her own relationship to psychotherapy, of which she had extensive experience as a patient: in 1930, she suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalised for a time, and in 1958 she began seeing a therapist again. During her hospitalisation, it seemed the divide between the institutionalised and those who worked for the institution was not so permeable. She drew her fellow patients, but never any staff, and, when asked by a psychiatrist if she would draw him, she replied that she wouldn’t: ‘You’re the enemy’. Who is the painter, then, in this therapeutic analogy? The enemy of the people or their champion? In Neel’s work, to find the answer, you have to look harder. ‘I paint my time,’ she said, ‘using people as evidence.’ ‘Using’ is a loaded word, especially for someone so highly attuned to mechanisms of power, exploitation and control. She didn’t turn her brush on herself until 1980; when she did, she was naked.

Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle, Barbican Art Gallery, London, until 21 May 2023

Listen to an audio version of this article on Spotify and Apple Podcasts courtesy of Dossiers HQ