Most of the West describes itself as part of a ‘global’ artworld. But how ‘global’ is that world in reality?

For the past 20 years, I’ve been moving between Taiwan, Germany and the UK. During that time I have noticed that it is not unusual to experience fatigue when operating in a second language. I am not alone in this experience, and more serious cases develop into xenoglossophobia (a fear of foreign languages), where the anxiety is likely to be connected to difficulties in performing in the new language and the consequent threats to or distortions of one’s self-image.

In London, for example, during a studio visit, I glimpsed a South Korean artist change his tone and posture to one that was far more authoritative when he was joined by a group of acquaintances who shared his cultural background. I had known the artist personally for a while, but at that moment I suddenly realised I had only had limited access to him, to a version of him that he developed after living in the UK.

It’s in response to this that, since 2013, I’ve been providing English-language tutorials for Mandarin speakers involved in contemporary art. The personalised sessions focus on reading essays or working on their artist’s statement. Most recently I helped an internationally recognised artist to relocate to the UK from Taiwan. With this artist’s rich experience of exhibiting abroad, it wasn’t the English language per se that concerned him; rather, what led him to me was his wish to prepare himself for a cultural translation and seek ways to socially connect. To prepare a person entering into an ‘unknown’ or projected social context in which they are seeking to develop a professional artistic engagement, a course should not be limited to the informative but also provide a cultural context in the UK that might allow the artist to navigate and develop themselves with a sense of authenticity.

Moreover, having witnessed the development of some of my students’ journeys towards integration, I see a greater effort needed for men to overcome some of these obstacles. I suspect this is heavily influenced by the conditioning of patriarchy and social hierarchy (based on age and career length) in East Asia. This is not simply to say that an East Asian man has to unlearn their male privilege in order to integrate; rather, it is a process of navigating both a different type of patriarchy and a situation in which the host culture (the West) is seeking to maintain a cultural and racial hierarchy with respect to the East. This creates a conflict.

Recently, while surfing the web, an algorithm brought up a clip of the first Chinese stand-up comedian to perform at the White House. The clip itself wasn’t the English-language White House routine from 2010 (which I’d already seen) but his appearance on a Chinese talent show, with a Chinese routine, in 2021. The live audiences for the two performances were local and could accurately be described as worlds apart, the only consistent element in the two events being the comedian himself. Through the screen, having access to both languages and approximate cultural contexts myself, the additional entertainment was in seeing the different personas on stage: in one setting as an immigrant representative given a platform on which to celebrate diversity through humour (the host introduced him in this way at the Radio and Television Correspondents’ Association dinner), and in the other as a respected senior comedian whose artistry has achieved the highest honour elsewhere. Both the comedian and the South Korean artist invest in a complex labour negotiation process between their ‘two’ selves, which in turn has a heavy influence on shaping their work.

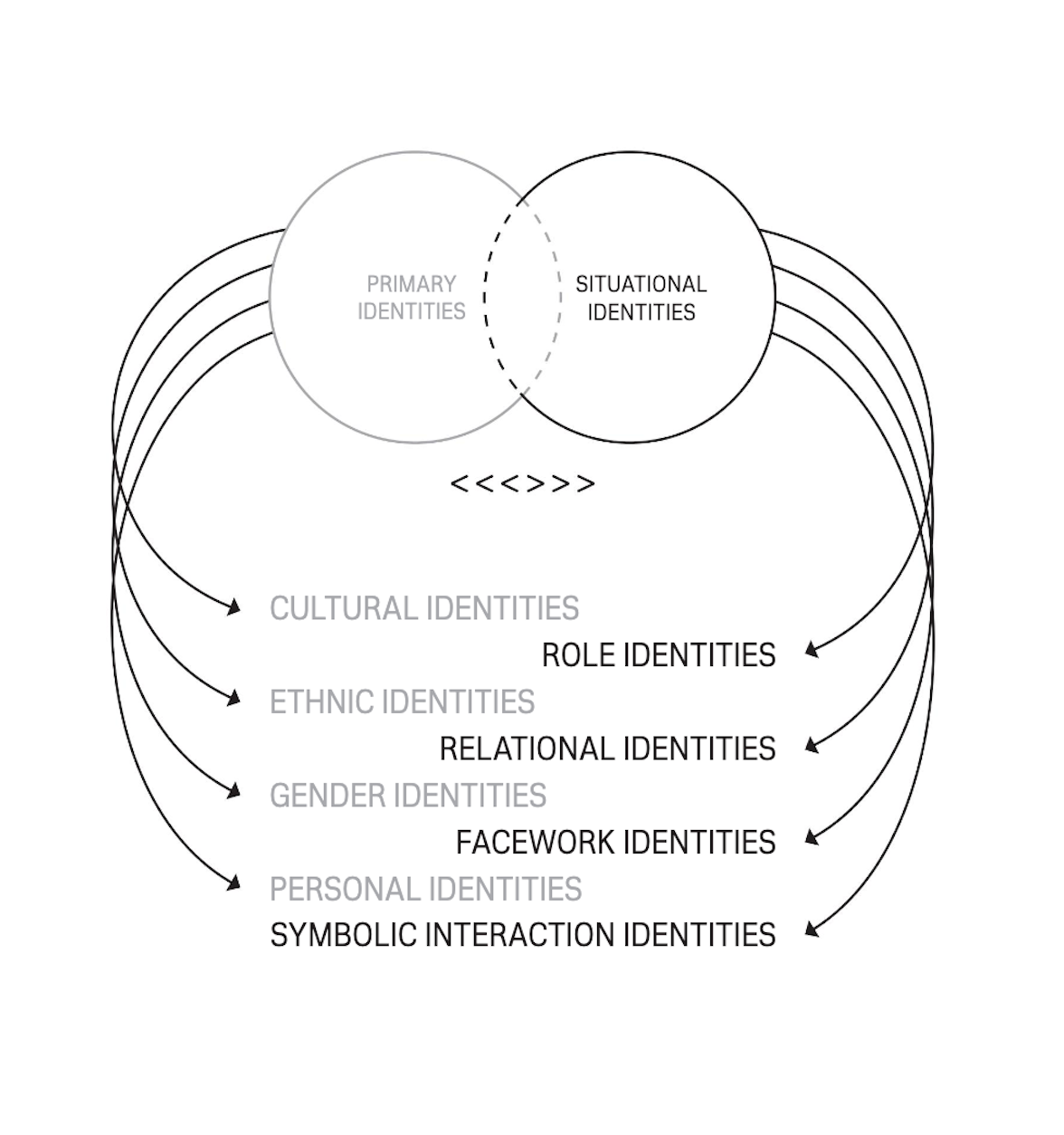

The Identity Negotiation Model (see graph) suggests that who you are can be agreed by members of a (new) community according to your relationship to eight specific areas. The primary identities are those you were born with, while situational identities are based on sociocultural conditions. ‘Facework identity’, for example, refers to defining oneself through etiquette in a dignifying way to all parties involved. This is manifest in East Asia when, for example, the most senior in the group often pays the bill for meals; or, on a grander scale, when the Republic of China leader Chiang Kai-shek waived all Second World War reparation claims from Imperial Japan to demonstrate nobility as a Chinese leader. Those gestures and actions that strongly define one’s identity in one context are unlikely to be received in the same way in the UK. The concept was introduced to relocating artists during sessions in which we discussed how they could leave a certain impression at work-related social events. When the negotiation process is off the mark, the consequences can be detrimental both personally and to career development. Especially today, when for artists a lot of invisible labour is put in outside of studio-based work: in networking, for example. (‘Today’s artists exist within a complex web of relationships’ – Fatoş Üstek). On top of the logistical, bureaucratical and financial setbacks relating to relocation, the migrating artist is taking the risk of interpersonal and identity conflict, and the anxiety of a loss of agency (under the structure of a Western narrative of the East), even if they are, after migration, at the heart of where the ‘global’ artworld is supposedly located.

Migrants in the past were systematically expected to culturally integrate. Both the East Asian artist and the comedian I mentioned previously responded to the integration process and navigated with the Western narrative of self: namely by setting aside South Korean etiquette or performing jokes about having a biochemistry PhD. As contemporary artists and cultural workers today, should we still be looking to integrate into the dominant culture to achieve connectivity and exchange? Does that simplify or even contribute to the prevalence of neocolonial forces in culture-making? As a result, is the global artworld heading further towards cultural homogeneity if a process of negotiation does not replace integration?

As a space for exchanging thoughts and reimagining the world, even when that process is against productivity or inconclusive, art is a crucial sector in which to start reforming the cultural power-dynamic. The identity negotiation process undergone by relocating artists and culture workers is one of constant observation and experimentation, searching for and deconstructing a known identity into a more complex one, all the time with the necessity of maintaining a sense of authenticity in order to establish their position in the host country. That authenticity requires that there be a real curiosity and investment in reciprocal work to demonstrate the acceptance of diversity within the ‘global’ artworld. To consider the process as a labour of research is to acknowledge the cultural authority that the host country has over its guests. For a global artworld to be ‘global’ beyond its face value, we need to investigate the response to that acknowledgement.