For artists Hamishi Farah and Arahmaiani, the experience of Los Angeles International Airport began as calamity and developed as farce

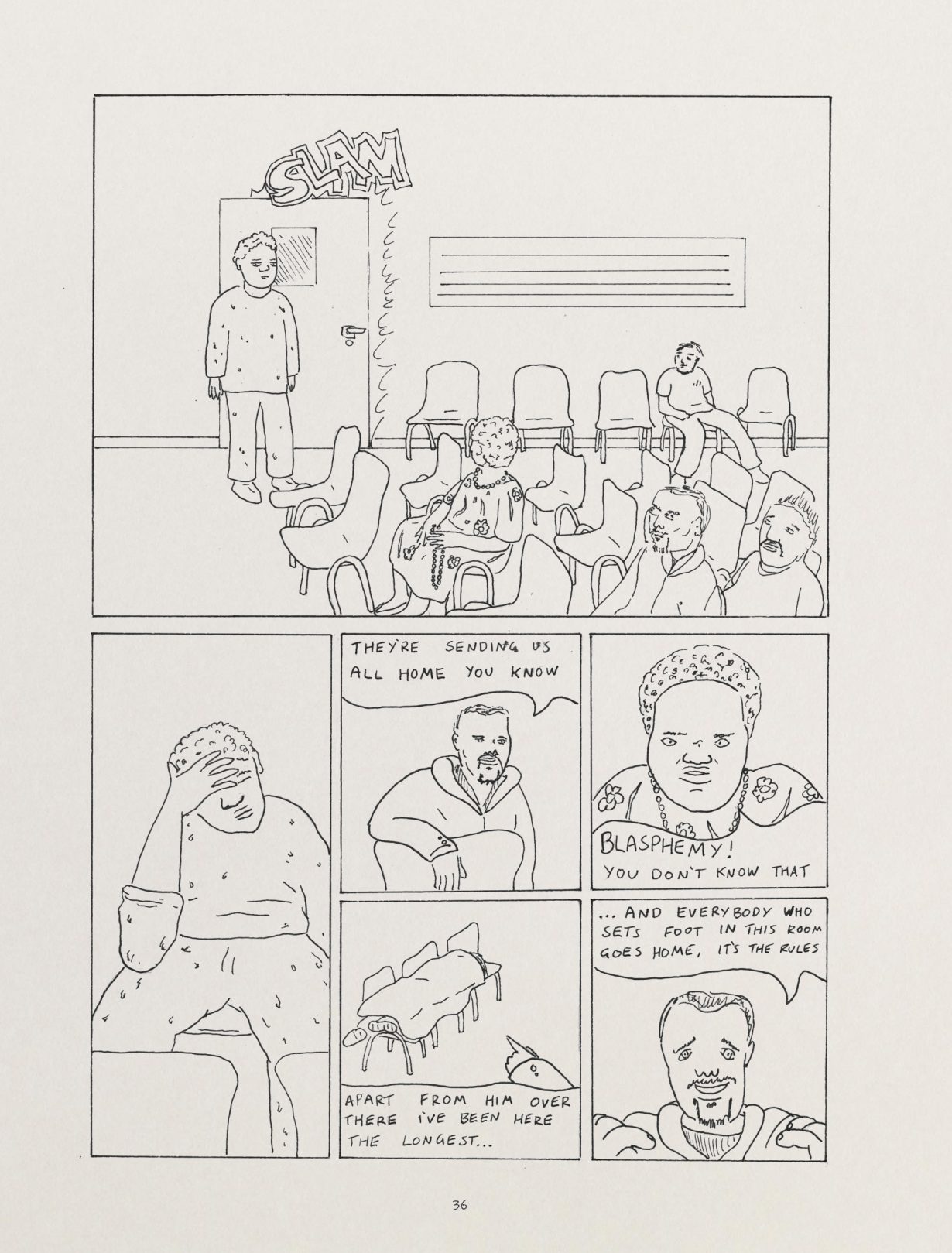

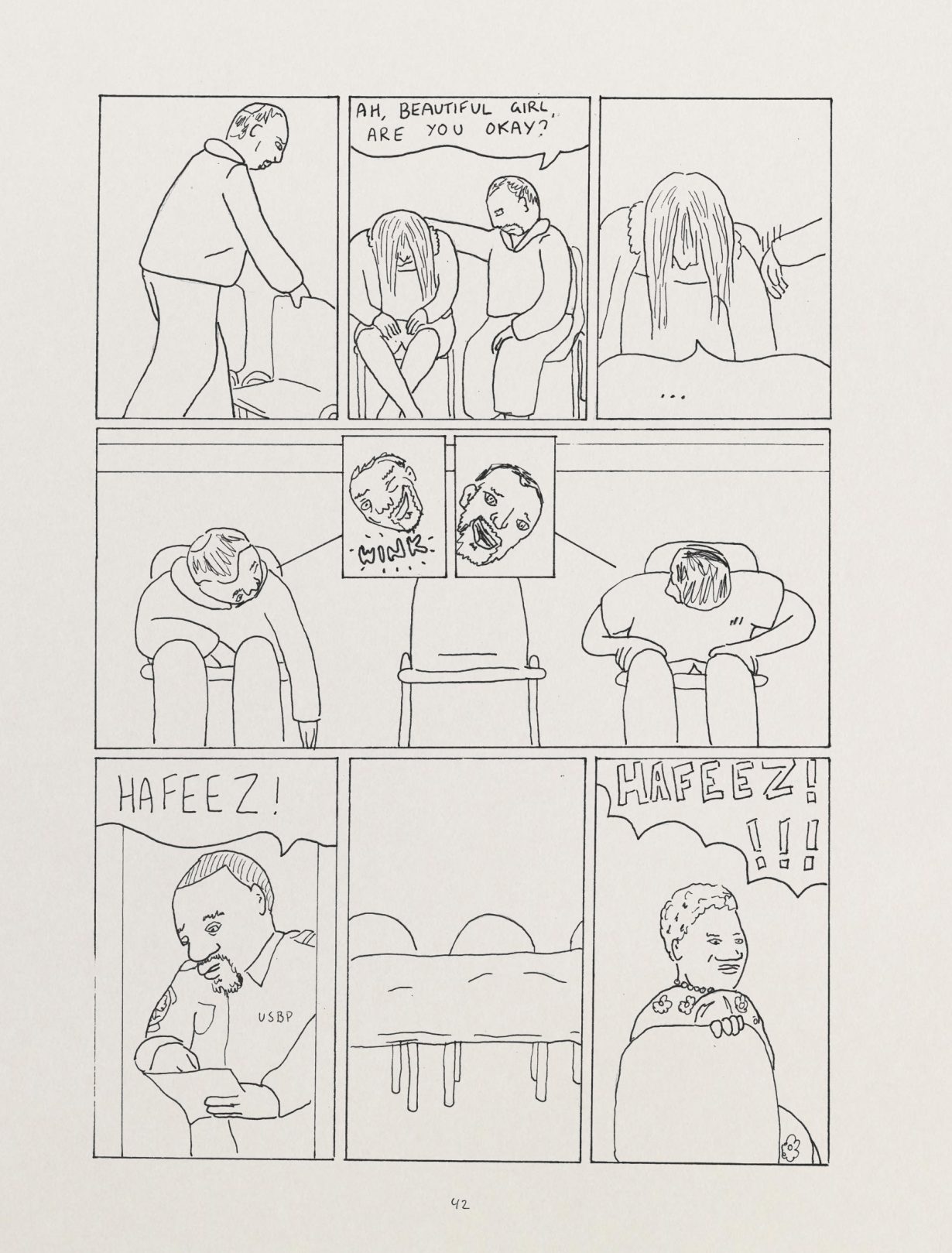

‘A child learns to see by noticing the edge of things,’ observes the narrator of Airport Love Theme, the graphic novel published last year by the artist Hamishi Farah. ‘How does it know an edge is an edge? By desperately wanting it not to be.’ The artworld suggests certain promises of egalitarianism and mobility, but failures of the latter belie the illusion of the former. Even if it ostensibly operates on the premise that ideas can move freely, often the people who generate them cannot. Airport Love Theme is a fictionalised account of real events. Farah was arbitrarily detained at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) in April 2016, flying from Melbourne to an art fair in New York. After 12 hours of detention and questioning, Farah was deported to Australia without explanation. The novel’s most overt fictionalisation is its introduction of a “psychosexual love triangle” to its plot; Farah looked, they told me, to manga artists like Satoshi Kon, who explore the psyche “in a psychedelic way”. One reason for the love triangle is that they wanted to avoid slotting neatly into a “trauma economy”. But it also underscores the surreal quality of the things that really did happen. It becomes a way to explore what Farah describes as “the libidinal economy of race”: the irrational, uncontrolled vehemence with which some, like those who detained Farah, absorb and express notions of racial hierarchy.

The mediated economy of the international artworld is supposed to be the thing that protects Farah. ‘Do you mind if I explain my working conditions?’ the artist asks the aggressive Officer Roberta Gawins, who has decided Farah intends to ‘illegally sell’ their paintings in the United States. It becomes darkly humorous how much hinges on Farah’s patient and evidently rehearsed explanation that their unfinished paintings are neither ‘products nor taxable goods’; that when finished they ‘can’t even sell them’, as they will be consigned to a gallery. The punchline comes when Officer DJ Envy, a benign Everyman type, asks whether this means Farah would not sell their art to someone on the street, even if they wanted to buy it. ‘No, I wouldn’t,’ the artist responds solemnly, though they could direct them to the gallery. ‘Ohh…,’ the officer muses, echoing a popular meme of the character Wee-Bey from The Wire (2002–08). ‘That’s kinda stupid.’ ‘We got ourselves a prima donna!’ exclaims Gawins. The artworld does not protect Farah; the artworld doesn’t even make sense.

Farah’s novel finds an antecedent in 11 June 2002 (2003), an installation by the Indonesian artist Arahmaiani. This work explores an event she experienced less than a year after 9/11, while transiting through LAX en route to Canada to give a talk. She was interrogated for seven hours by seven officers of various cultural backgrounds, many of them Muslim, then told, as she recalled in a 2017 talk, that she would be taken to “a special place for foreigners who have problems”. Fearing the vagueness of this proposition, she insisted on staying, and was eventually allowed, on the condition that she remain under guard, to go to the hotel room her airline had booked for her transit. She expected that the guard, a fellow Muslim from Pakistan, would remain outside – not that he would insist on staying in her room all night. “But I will be in trouble if you run away,” he said, although the room was on the 20th floor. “I’m American and I’m doing my duty.” Arahmaiani’s installation, which depicts a hotel room, recreates in a seemingly gentler vein that breach of the artist’s private sphere. A pair of pantyhose lies twisted on the neatly made bed; a Quran rests on the pillow. Two antique Coca-Cola vending machines flank the diminutive chamber, emblazoned with the slogan Erfrische Dich (‘Refresh Yourself’). Fabricated and exhibited first in Pirmasens, Germany, 11 June 2002 was then shown at the Indonesian Pavilion for the 2003 Venice Biennale: an exposition whose structuring in national pavilions demonstrates a mixed tendency to reify borders as well as to create opportunities, as the art historian Caroline Jones has written, for ‘the problematization of both spectacle and the ethnic state’.

Coca-Cola is a common motif in the artist’s work as a stand-in for the forces of globalisation. It is perhaps Arahmaiani’s spiritual bent, as well as her commitments to protest and to work that can be engaged with by a broader audience, that are responsible for the artist’s investment in a recurrent set of talismanic symbols. In Etalase (1994), a Coca-Cola bottle appears in a vitrine, alongside items like a Buddha statue, condoms, a box of sand and a Pakwa mirror. The placement of condoms in adjacency to a Quran generated controversy in Indonesia. This despite, as she notes in the 2017 talk, contraceptives being central to family planning, a government priority at the time; the family of Indonesia’s second president, Suharto, sensitive to a business opportunity, built the largest condom factory in Southeast Asia. The artist has faced arrest, criticism and death threats during her career, requiring her sometimes to leave urgently and live “nomadically”. “My position is funny,” she says, because she is at once regarded as a “Western agent” in Islamic society and a potential terrorist in the West. This bind is reflected in a different way in Farah’s novel, whose narrator is racially profiled over a Somali heritage from which the character has experienced painful estrangement.

11 June 2002 also expresses a kind of ‘love theme’ in its use of hand- drawn hearts. But the possibilities of love – whether love of American culture, intimacy with the viewer as voyeur or the self-regard of the room’s implied inhabitant – are ironised, thwarted. For both artists the experience of detainment began as calamity and developed as farce. When Arahmaiani finally, warily, fell asleep in her hotel room, she was awoken by the loud snoring of her detainer, who also fell asleep. In the morning it was she who had to shake the man awake, reminding him of her connecting flight. Likewise, the incident in Airport Love Theme in which a guard chooses to screen one of his favourite movies, Coming to America – the 1988 Eddie Murphy romantic comedy about a wealthy African prince playing poor – really happened. (Farah saved the DVD and framed it, exhibiting the disc and case in 2020 under the title Horcrux.) The cold impersonality of the experience overlays the human and intimate aspect. It is the third time Farah’s narrator has tried to enter the United States, and their ‘third time in this room’. ‘They don’t remember me,’ they note, but ‘my phone remembers the wifi.’

Both artists draw heavily on that human and intimate aspect. While the subject seems inherently to entail isolation, both works find a way to be about, or to incorporate, community. Farah’s novel explicitly names the theme of the oppressed subject being called upon to enforce racist border regimes. Arahmaiani’s vexed recognition of her Muslim interrogators surely informs the tone of 11 June 2002. Both artists have a clear sympathy, even affection, for some of their detainers while remaining appropriately critical. ‘Can I make them love me? The way I love their blackness[?]’ Farah’s narrator wonders. Though it certainly does not engender love, in a way it is from that same impulse that they tell the most fanatical guard, ‘You seem pretty hype to do this white ass job’. Another community of Airport Love Theme is the fellow detainees ‘held at LAX April 25, 2016’, to whom the book is dedicated. The narrator is ashamed to adjust so quickly to detention; it is a reminder of how easily some of us acclimatise to circumstances of abjection. But if they feel ‘at home’, it is also because these castaways from global empire form, with fluctuating intensity, a people of their own.

Arahmaiani states that she has been offered a variety of passports over the years: Swiss, German, Australian, American, Chinese. She has never taken up the offers, because Indonesia forbids double citizenship, and despite the difficulties of working there, Indonesia is the source of her “inspiration and life aspiration”. Is this, anyway, to be considered proof of the artworld’s promise of mobility made good? It is too simple a formulation. Forces like globalisation make movement possible; they also make it necessary. The mirror image of the dream of mobility is the reality of displacement, and as Farah’s novel attests, many of us now possess histories and identities that are incomprehensible without them. There is only the possibility, per Arahmaiani, of choosing which communities we wish to be accountable to, which spheres of living can sustain us and how, in that way, the world can be fashioned and refashioned.

An exhibition of work by Hamishi Farah, Dog Heaven 2: How Sweet the Wound of Jesus Tastes, is on view at Kunsthalle Fribourg through 31 July

Yen Pham is a writer from Australia

Originally published in the summer 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia