All I need is a little bit of everything at Gagosian, London follows three decades of work suffused with existential angst

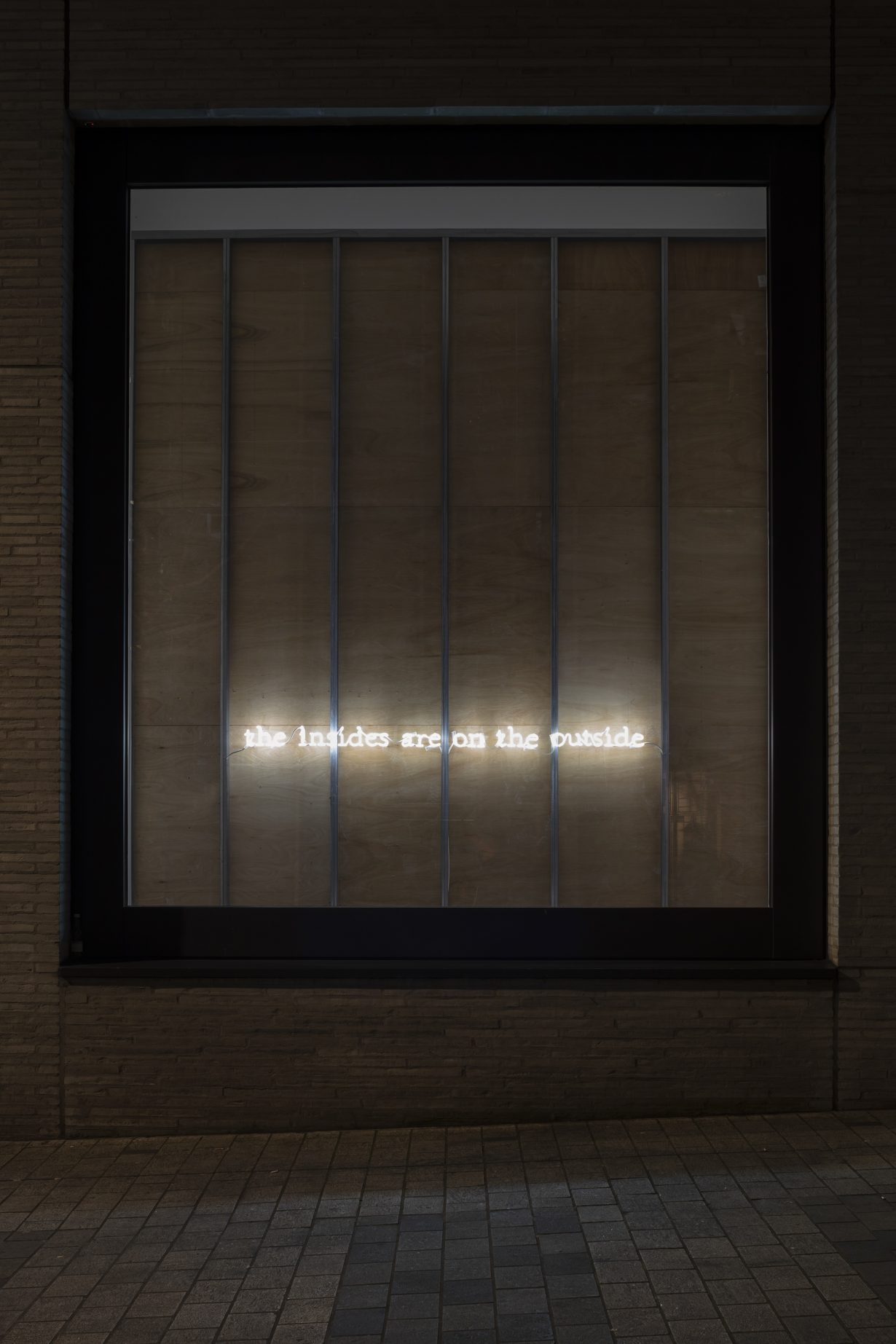

A logophile’s wet dream, All I need is a little bit of everything features sentences arranged like so much concrete poetry, set in different typefaces and operating in different languages, pasted, carved and spray painted across the gallery’s interior and exterior walls, or installed as scrawling neons that illuminate entire rooms in single blocks of colour. The entryway is bathed in a sickly pink glow emitted by a red neon sentence written in Japanese (It’s Coming, 2002). On an adjacent wall, the Pepto-Bismol-tinted words I am the author of my own addictions (2010) are gouged into the wall, plaster dust littering the floor below. As one of the opening works, it’s a bold acknowledgement of personal accountability; a prompt for viewers to check themselves against.

Gordon has, for more than three decades, made work that’s suffused with existential angst (think of his light and wall text installation From God to Nothing, 1996, not presented here, in which the artist lists a lot of things he fears, or Film Noir, 1995, which is shown here, and records a fly stuck to a tabletop by its wings, that struggles to free itself but eventually dies – a short meditation on sadism, guilt, death and morality). And in that respect, All I need… risks feeling a little tired – with several sentences melancholically wondering where does it hurt...(2019) or how much can I take? (2020), while awash with neon lights that evoke in the rooms the atmosphere of an empty nightclub. But the show is saved by the collective visual impact of 46 such missives assaulting nearly every eyeline – which makes it impossible to escape the glare of his plaintive words, putting in the mind of the viewer thoughts like: How free can we really be? (2017).

Still, there’s a sense of artworks being recycled (both in form and subject matter), which to be fair to Gordon, has been a regular feature of his practice; and perhaps it also alludes to a wider point about how our lives, and the way we choose to live them, are shaped by the stacking of our experiences. In his recent video 2023EastWestGirlsBoys (2023), a closeup of the artist’s bloodshot eye fills the entire frame, with neon words like ‘stud’, ‘majestic’, ‘strip’, ‘non-stop’ and ‘naked’ replicated from Soho shop signs beamed across the pupil and iris between each slow-motion blink. It’s a coda, perhaps, to Phantom (2011), his collaboration with musician Rufus Wainwright, which films a closeup of the artist’s slowly weeping eye painted with glossy black makeup. Unlike Phantom, however, 2023EastWestGirlsBoys is a soundless video, in which words – instead of music or literal tears – are tasked with the job of summoning an emotional response from the viewer. A sort of Hitchcockian double-voyeurism emerges from the closeup filming of the artist’s eye that looks out at the viewer (through the mechanical eye of a camera lens) as they observe and perhaps recognise some of their own impulses and desires reflected in those neon words.

Phantom and Film Noir are included in Gordon’s Pretty much every film and video work from about 1992 until now (1999–2024), a haphazard oval-shaped installation that takes up the gallery’s largest space and features 109 televisions and monitors stacked above one another on crates, emitting a cacophony of noise and imagery. The installation is simply an amalgamation of Gordon’s past works; but it can also be interpreted as a self-portrait of the artist. Walking around its circumference feels a bit like peering into Gordon’s psyche, bringing to mind the cliché about life flashing past before you die. There’s also an odd sort of disconnect between Pretty much every film and video work… and the sentences sprawling across the previous gallery rooms – allowing the exhibition to settle into the strange space of inference between image, word and translation.

Spend enough time in All I need and the experience starts to get a little trippy – like the moment, in a nightclub, when you realise that trying to communicate with one another using words is futile, and at some point (depending on what substance you’ve exposed yourself to) it all turns into nonsense anyway, so you may as well just enjoy the lights and music. There’s a seemingly small moment of respite from the mounting sense of introspective claustrophobia that All I need induces in the form of Afterturner (2000). On the far side of Pretty much every film and video work, two peepholes (one above the other) are drilled into the wall of the gallery; looking through, your eye makes quick adjustments between words that are pasted onto the window, and the world outside. But just as a glimmer of freedom is presented before you, the words ‘Bad is good… Good is bad’ come into focus – a reminder that we can’t ever really escape the confusing, and at times contradictory internal worlds we build around ourselves.

All I need is a little bit of everything at Gagosian, London, through 15 March