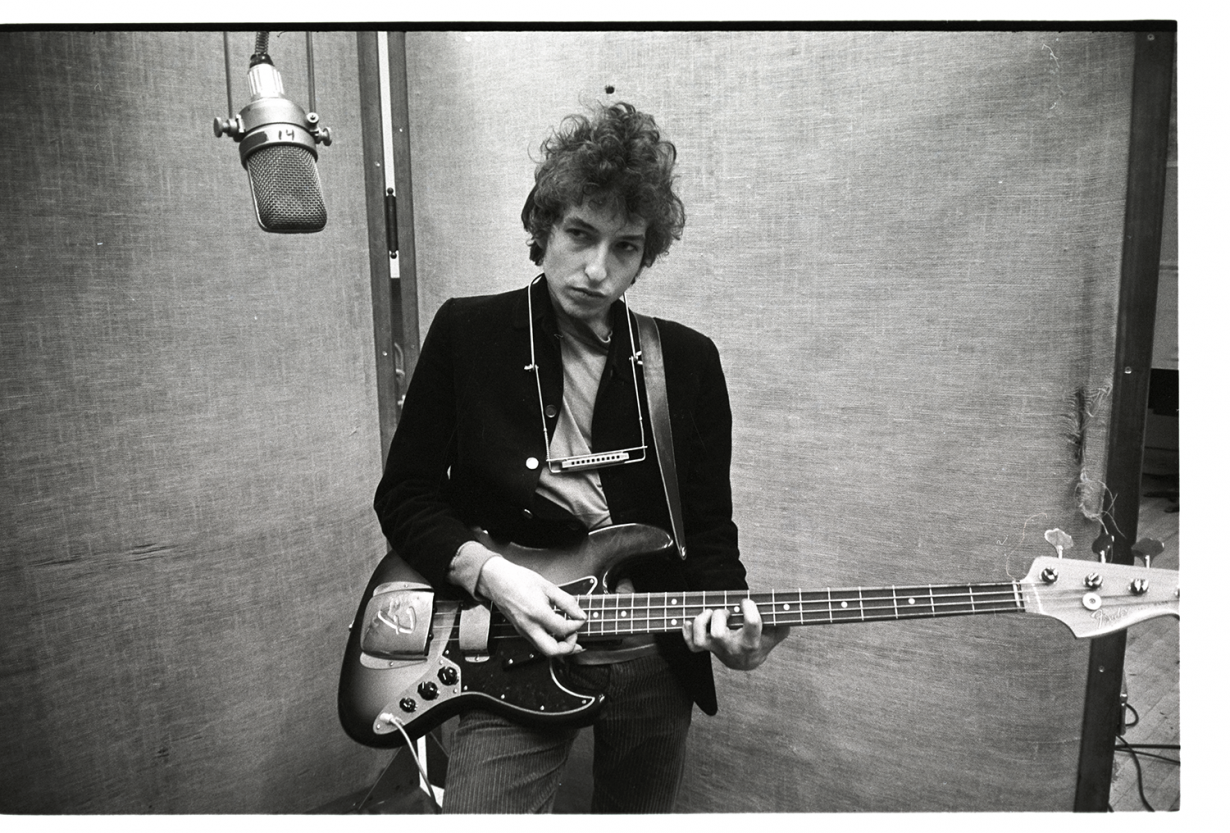

An exhibition of Bob Dylan’s paintings at Miami’s Frost Art Museum draws from movie stills to create scenes of everyday, isolated life

The paintings that make up Bob Dylan’s 2016 series The Beaten Path take us across deserted American landscapes, many offering up places with more of a past than a future: a motel sign on Route 66, a fenced-off abandoned school, broken train tracks on a beach, leading nowhere. These are spaces emptied of people, yet filled with their traces.

By contrast, Dylan’s 2021 series of paintings Deep Focus – now on view at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum – moves into the cities of America and populates these places with humans of all kinds.

Some are gathered round: four men in a card game inside; others playing dice outside; a jazz band. We see the last moments of a boxing match, a batter at the plate, in the two sporting events to which Dylan consistently returns. There is a lot of alcohol and lots of smoking.

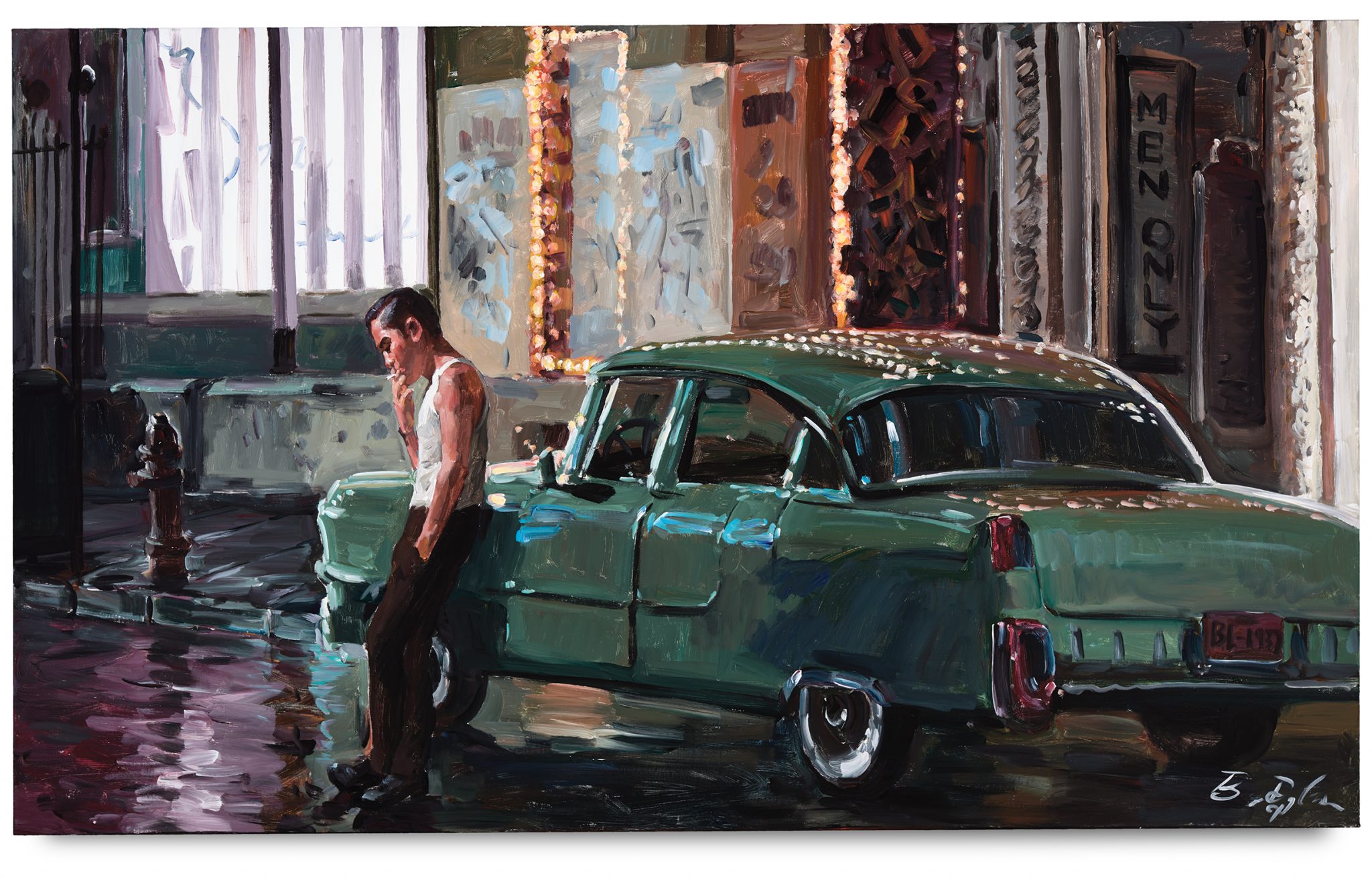

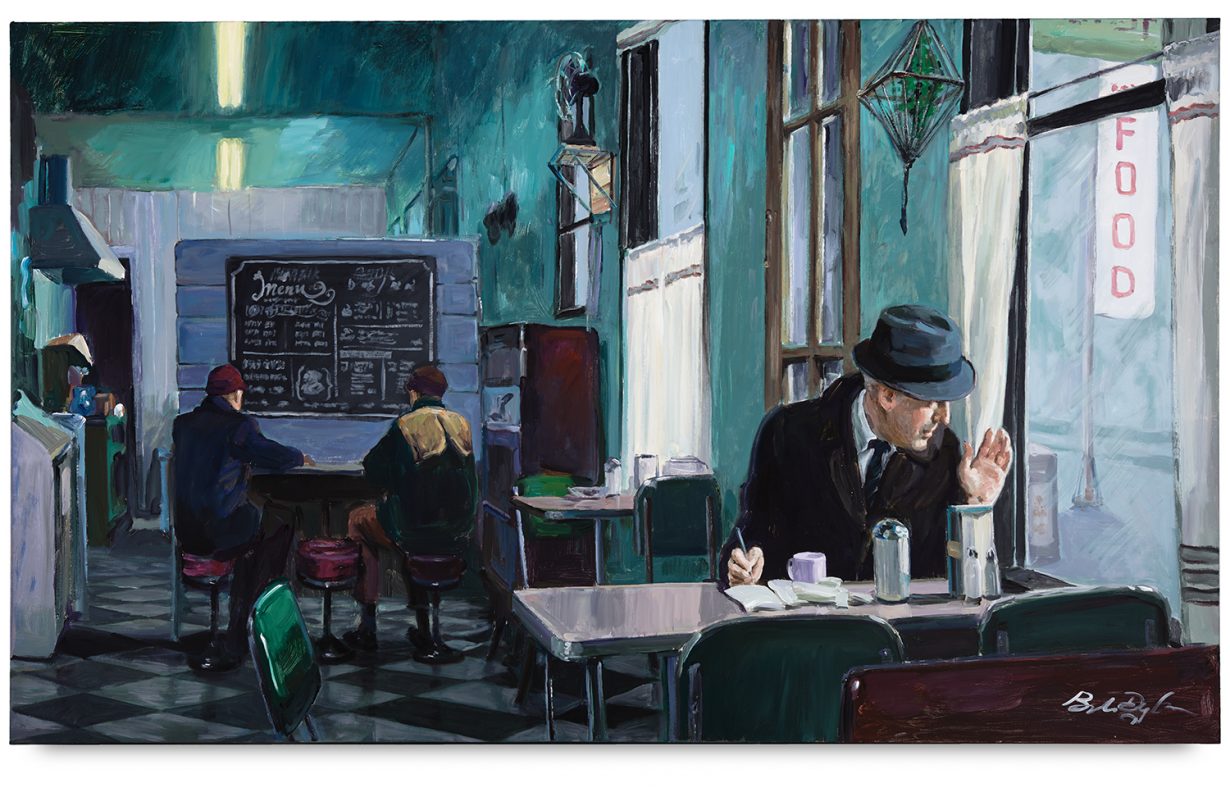

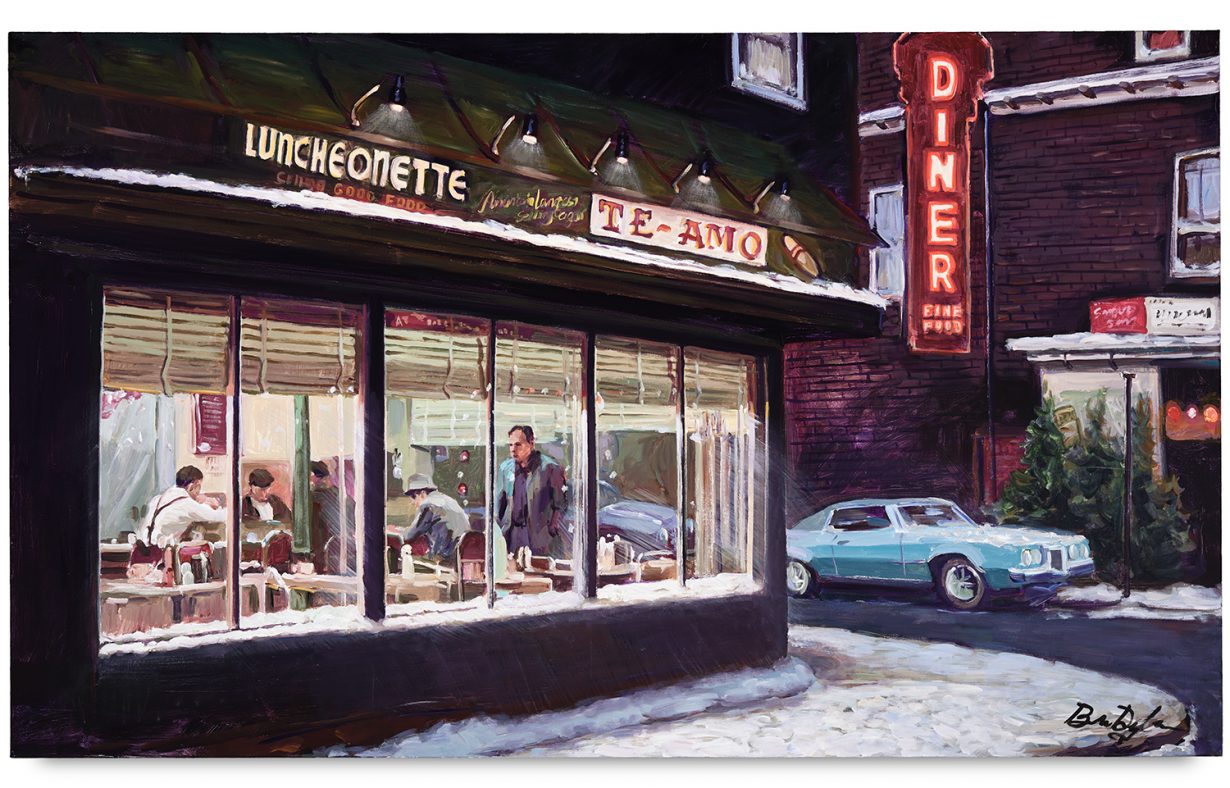

Deep Focus may show us everyday life, but it is one in which individuals are isolated: a woman drinking and smoking at a bar; closing time with a man passed out on his barstool; another man looking out a diner window, his right hand paused from writing in a notebook; a woman flopped over the back of a car seat, an open bottle on the floor; a man in an undershirt in a rundown shack; a woman lying on her back on the roof of a New York tenement.

Elsewhere there are just the traces of isolation, as in Motel Still Life (2021) with its single toothbrush, single shot glass, whiskey bottle, radio, and book, maybe a Gideon’s bible. This could take you back to the strange hotel and neon burnin’ bright in Simple Twist of Fate (1975), its character feeling that emptiness inside. The songs of Blood on the Tracks (1975) are rightly connected to Dylan’s increasing interest in painting back then. In Deep Focus, Dylan works from movie stills to create memories of such worlds: songs that tell stories and paintings that capture frozen fragments of movies, both containing multitudes.

At a 2019 exhibition I kept coming back and getting up close to Train Tracks (2008) from the Drawn Blank series, Dylan’s answer to Monet’s multiple versions of the Japanese footbridge (1899) – seven paintings whose colouration varies and deepens as they cluster around and lead the eye to a monumental masterpiece nine feet by six, colours from across the palette – blues, greens, purples and pinks, the white steel rails cutting through them with a sky on fire.

In an interview on 30 October 1977 as Dylan was putting the finishing touches to his film Renaldo and Clara, Allen Ginsberg put the question “What attracts you, as a poet, to movies?” “If film was around when Da Vinci was operating,” said Dylan, “he’d have made film.” And now he has returned to the genre that has always been important. “All these images come from films,” he says of Deep Focus. Always the inventor and the teacher, Dylan has created a new imaginary, stopping time, freezing it and reimagining it but also allowing us to step into our own memory and see the film with new eyes.

Identifying the origins of the paintings of Deep Focus is something of a game, gratifying in the same way that for me hearing in a Dylan song a line from Homer, Blake, or Whitman is gratifying. But that is only the beginning. What matters is what Dylan creates from those lines in his songs, or in Deep Focus from the images. Who is the woman with the dog in Walking the Dog (all works 2021), and why does she seem in such a hurry? Where is she and how does the laundromat come into it? Hideaway Woman has stories to tell, none of them too happy from the looks of it. In Novelist we wonder what the subject is writing, who he is looking at off-screen through that window, whether and how the experience and observation of his viewing will be communicated through his imagination to whatever he is writing in that notebook.

Deep Focus is often interested not so much in the foregrounded action as in what is going on in the background, off to one side or another. The new series participates in that process, creating curiosity about what we see outside a diner window, on a billboard or menu in the background, on the face of a man in the crowd of a boxing match, a number of figures visible through the open door of a trailer, a painting on the wall of a bedroom or above a bar.

The movie stills with which Dylan works are said to show ‘the camera’s potential to manipulate reality.’ Not just the camera’s. There is a lot of creative manipulation going on in Deep Focus. The solitary figure in Sugar Bowl (2021) can be identified as Vance, the biker played by Willem Dafoe in the 1981 film The Loveless. The retro diner, like the gas pump outside, is in keeping with the film’s setting in the late 1950s. But in the still Dylan painted from there was another character, a waitress who has just poured coffee for Vance. In Sugar Bowl she’s not there, leaving Vance to brood alone, an ominous pointer to the mayhem and darkness with which the film closes. And a clue to his identity is there in the bike parked outside the diner window, a Harley Davidson 1200 cc Type 74, brought into the world, like Dylan, in 1941. The dramatic setting could take you back to Hibbing, to a photo of the fifteen-year-old Bob on that bike precisely. Vance has been transfigured, to use Dylan’s own language, through his brilliant reading, manipulation, and reinterpreting of the image – a new sort of self-portrait, even.

There is a lot of such transfiguring in Deep Focus. In one painting, Frank and Buddy (2021), we see a storefront with the number 259 above the sign ‘A. Zito & Sons. BAKERY.’ Zito’s was a famous Italian bakery in the Village at 259 Bleecker Street, the longest operating business on the street, open for 80 years until it closed in 2004, and now an Italian eatery with the allusive name Baker & Co. Dylan’s first apartment in New York, at 161 West 4th Street, was just a block away from the bakery, which is also a five-minute walk from the townhouse he later owned on MacDougal Street. The real bakery is dead level with the street. Our painter has elevated it, giving the street-level door to the left a set of three or four stairs, at the top of which two black men converse. They are dressed in 1940s-looking suits and stylish hats, and one is smoking a cigarette. Someone will in due course track down the movie they come from. Between them and the bakery window is a barber pole, the timeless icon that is a leitmotif in Deep Focus.

Beneath the bakery in the space that the elevation opens up is a sign ‘FRANK’S BARBER SHOP.’ That could lead us to the New York Times obituary of 1 October 1998 for Charlie Zito, son of founder Antonio: ‘Mr. Zito loved Sinatra at least as much as a great whole-wheat loaf. When the singer was in town, the story went, he would personally call Mr. Zito to deliver bread personally to the Waldorf-Astoria.’ So Dylan, who has recently recorded five discs of mostly Sinatra songs, lifts Zito’s up a few feet and gives Frank his own basement barber shop, right under the bakery he loved. The painting unites all of the components into one, allowing our imagination to create a Zito’s that belongs at the same time both somewhere and nowhere in the 80 years of its existence.

Film has always been in Dylan’s past. In his early days in Hibbing it was his lifeline to the outside world through the golden years of Hollywood that coincided with his teens. It connected him to the wild west, to ancient Rome, to Shakespeare, to James Dean, Brando and Peck. These paintings bring the film and characters of his and our past into the present. Just like the scenes he has been creating in song for all these years, those of Deep Focus will keep people busy for years to come – busy not just mechanically or serendipitously identifying the movie scenes that have become his new palette but also pondering the ways he creatively transforms those scenes and brings to our consciousness “the different predicaments that people find themselves in,” as Dylan has said of the series. These paintings form a screenplay for our own situations: “life as it’s coming at you in all its forms and shapes.”

This essay is an edited version of Richard F. Thomas’s original text Dylan Transfigured, 2021

Retrospectrum: Bob Dylan is on view at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum until 17 April 2022