An invisible order underpins the works by this pioneer of computer-generated art

By Martin Herbert

A couple of things that are useful to know about Elena Asins upfront: she was a pioneer of computer-enabled art and, for a while, studied semiotics with Noam Chomsky. The latter fact is relevant insofar as the Madrid-born artist, who died in 2015 aged seventy-five, used digital animation, sculpture, concrete poetry and a variety of two-dimensional works to figure, in sequential nonrepresentational art, something analogous to Chomsky’s ‘universal grammar’: an underlying set of structural rules posited as innate to all humans. Asins’s work, powered by the energies of cybernetics and combinatorial theory – such as Ramsey’s theorem, which argues that disorder always seeks to resolve itself into regularity – suggests the invisible presence of systems underlying everything.

The scope and, frequently, Euclidean rigour of her practice were on full display at a 2011 retrospective in her home city’s Museo Reina Sofía. KOW, meanwhile, doesn’t even attempt to compress it into the one upstairs room they’ve devoted to her. Instead, they offer a tightly circumscribed sample, seemingly pulled from a dusty archival box: ‘rare works from the 1980s’, which turns out to mean an austere selection of computer printouts arranged in grids and friezes, in which black abstract forms pass through sprightly modulations, underwritten by alien logic.

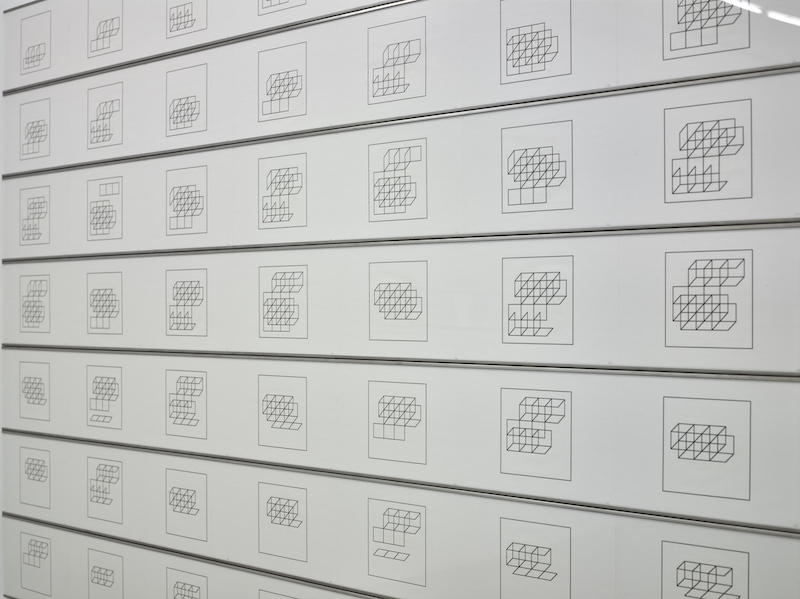

Reading one long framed strip of 18 conjoined pieces of dot-matrix printer paper – dated 1989, and seemingly titled Canons 18/11 (there is no list of works) – from left to right, we first see one biomorphic blob hovering above another. On the next sheet, it’s joined by a third, while one of the preexisting ones has morphed slightly. What follows is constant quiet permutation, shapes changing, vanishing, reappearing, the whole looking like not only animation cells but a set of dance steps without music, the glyphs finally shrinking and winking out. Asins, here and elsewhere, mobilises sheer aesthetic confidence. Just as you don’t have to be a musicologist to note the grace and sense of resolution that permeates Mozart’s music – which she also studied closely – these works make intuitive sense even while suggesting a meaning or purpose you can’t quite grasp. In 3 in 3 Perspective Scale 33 newplan (Nr.1-49) (1989), a 7×7 lattice of variously agglomerated Necker cubes – the ones with ambiguously reversible perspective – permute mutely from sheet to sheet. As you look, noting where a section of geometric architecture has vanished and another, or several more, appeared, Asins’s work appears in dialogue with both Minimalism and the allover painting that preceded it – this sequence, large as it is, insinuates itself as an extract from an endless process.

Asins’s idealism still resonates, though an exhibition titled Machines to Change the World in 2020 can’t escape irony and melancholy: count the ways that computer technologies have indeed changed our world, from job automation to the isolation effects of social media to drone warfare. These works, beamed in from another time, implicitly indict our own, even while they offer a bleep of theoretical optimism: things might seem chaotic to us, but in Asins’s universe, disorder is just an illusion.

Elena Asins, Machines to Change the World, KOW, Berlin, 15 February – 14 March 2020

From the April 2020 issue of ArtReview