At MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, an exhibition proposes a new story that goes beyond the confines of nationalist tropes

A seemingly trivial art-historical mistake provides the intellectual springboard for part one of ‘Collecting Entanglements and Embodied Histories’ (a four-part exhibition series-cum-dialogue between the collections of MAIIAM, the Galeri Nasional Indonesia, Berlin’s National- galerie and the Singapore Art Museum). Deep inside ERRATA sits a display case containing archive materials from Singaporean researcher-artist Koh Nguang How’s 2004 investigation into an error he found in the catalogue for the Singapore Art Museum’s inaugural 1996 exhibition. Evidence outlining why Chua Mia Tee’s National Language Class – a cornerstone painting within Singaporean modernism/ nationalism – should have been dated 1959, not 1950, sits alongside flyers, a timeline and a rationale for Koh’s enquiry: ‘He understands that none of the pieces of the puzzle is too small to be insignificant, and it is his persistence and consistency in pursuing the intricate trivialities that enables the completion of historical construction’.

In the wall text, Koh’s corrective impulse is equated with MAIIAM and the socially engaged practices it traverses. From the 1990s until today, this private museum’s founders, Eric Bunnag Booth and his stepfather, Jean-Michel Beurdeley, have been steadily acquiring Thai contemporary art that resists the stultifying state-sanctioned rubric of nation, Buddhism and monarchy. Their collection – this show’s departure point – is nothing less than ‘the manifestation of errata in Thailand’s public and some private collections’, the intro posits, comprising works that ‘discursively contemplate the errors in the grand narrative of national centric art works’, or deal with ‘absent or untold history from the region or beyond’.

Unlike Koh, however, ERRATA does not painstakingly unpick said errors – the art-historical lacunae and mistakes MAIIAM is attempting to redress through its collecting habits are to be inferred, not illustrated. Instead, the works by Thai artists are grouped into six chapters that resonate beyond national borders courtesy of loans (video art, mostly) from the other museum partners, as well as pieces from its growing Southeast Asian collection. Together, these themed constellations demarcate loosely what MAIIAM stands for – its left-leaning preoccupations and ideological affiliations – but not exactly what errors it is reacting against.

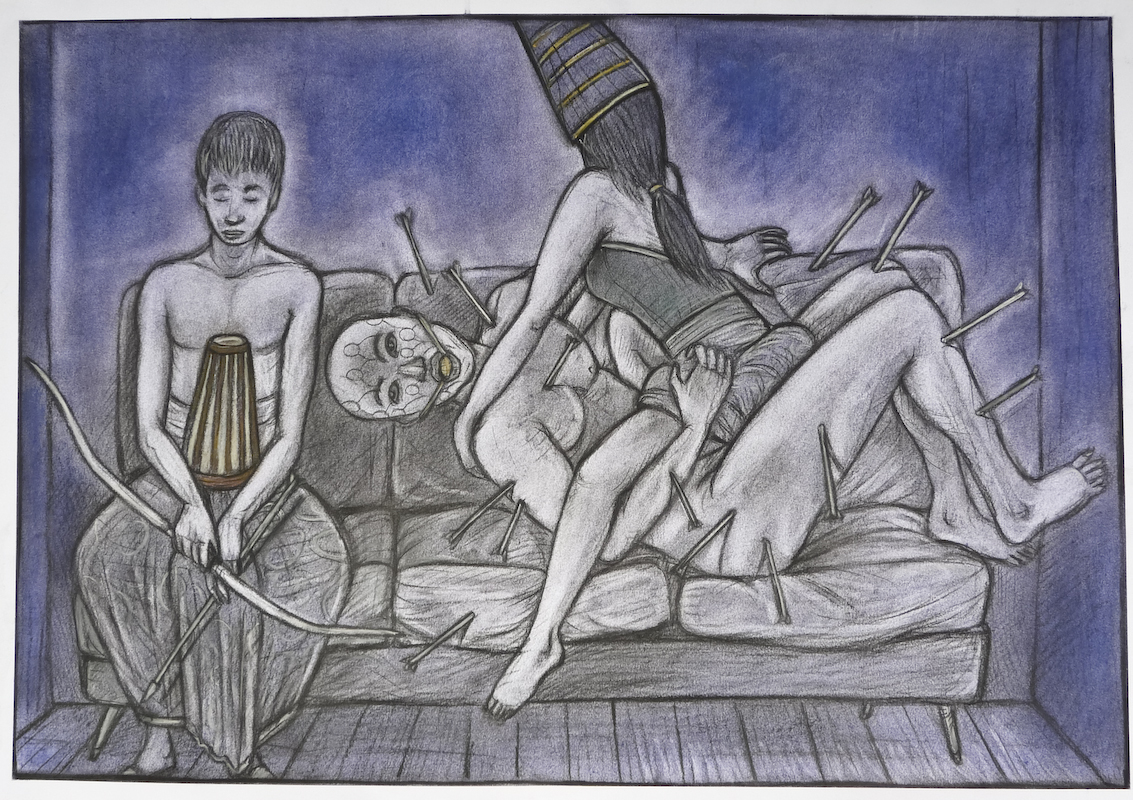

In the chapter ‘On Contesting Grand Narratives’, four artists subvert or question the influence of the Indian folk epic Ramayana on Southeast Asia’s aesthetic and sociopolitical landscape. Anuwat Apimukmongkon’s mongkut (Thai crown), fashioned from rough-hewn corrugated paper – a mordant critique of Thai Hindu-Buddhist regalia – is a highlight, as are the five pastel pen drawings by Agung Kurniawan, each rendered sumptuously and broaching queer issues in Indonesia through a reinterpretation of the Ramayana’s love triangle.

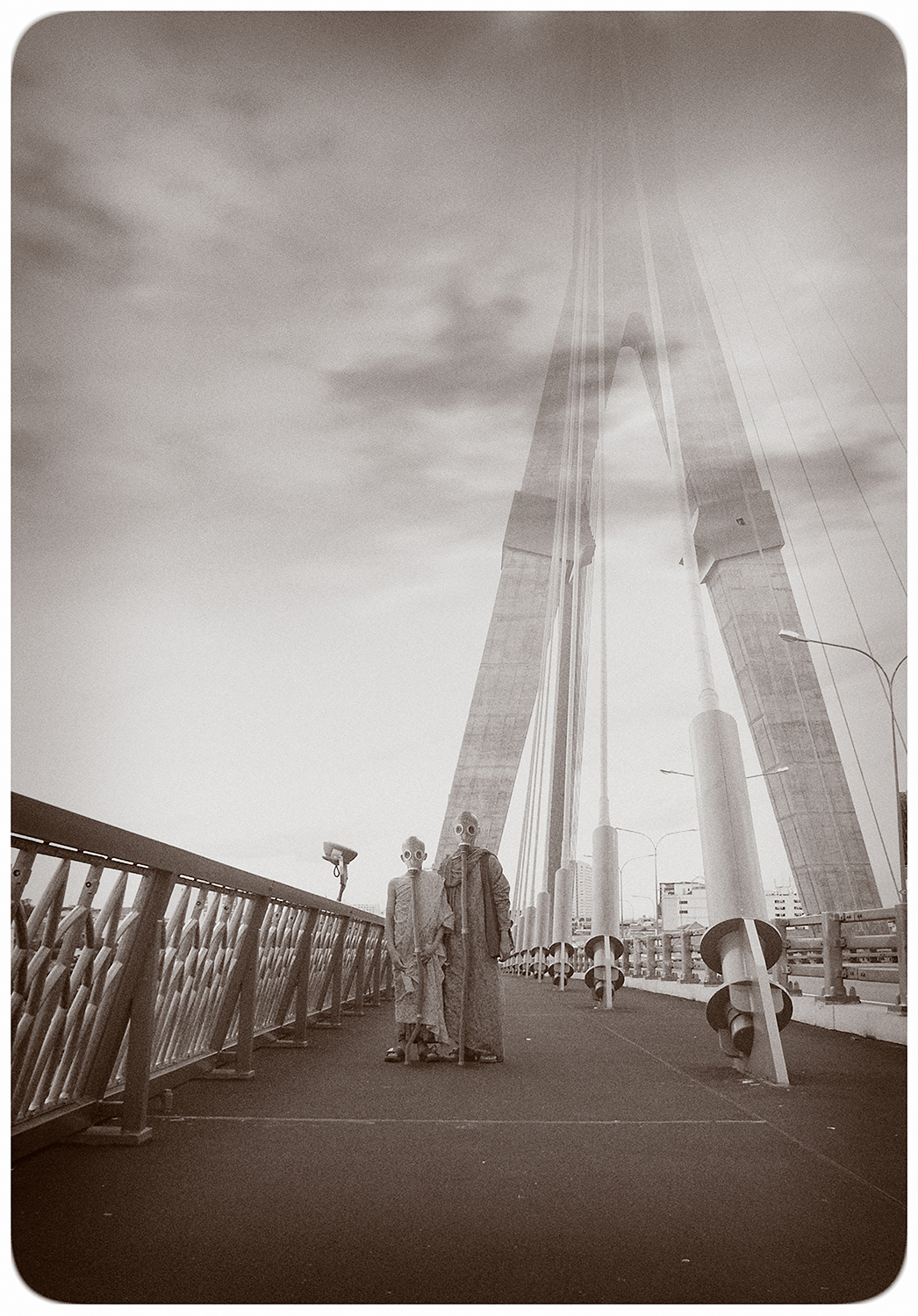

The biggest grouping, ‘On Cold War Remnants’, explores how repressive state ideology and anticommunist policy was, during the dawn of the so-called American Era, contested by marginalised groups near and far. Setting the tone is Oh Yoko! (1973), Keiichi Tanaami’s cute, psychedelia-filled animation for John Lennon’s song of the same name. Its breezy lyrics remain audible as you take in the half dozen works, from a fibreglass recast of Indonesian sculptor-activist Dolorosa Sinaga’s bronze sculpture signifying women’s comradeship during the Suharto regime (Solidarity, 2000), to Tisna Sanjaya’s fantastical illustrations depicting bacchanals of corruption, to painting series appropriating images from the Bangkok street massacres of 1973 and 76 by Arin Rungjang and Thasnai Sethaseree.

Beyond a dividing wall are two works by Joseph Beuys, including a video projection of his three-day live-in with a wild coyote, I Like America and America Likes Me (1974). The penetrating influence of his activism and social sculpture on Thai artists and events is reified here through a juxtaposition with three works, including photograph documentation of Kamol Phaosavasdi’s declarative 1985 performance critiquing the then stagnant Thai art scene (Song for the Dead Art Exhibition (1985), 2014).

Further on, bold displays of local and international works also invite rumination on the female body as a means for exploring identity politics or social critique, on the alternative histories of sites of social trauma or colonial resistance (from a rebel village in Thailand’s Deep South to a slum in Jakarta), and on artistic challenges to official historiography. And three more archives spotlight marginal events, collectives and artist-run projects, including the Beuys-inspired Chiang Mai Social Installation festival (held for four editions during the 1990s), and the forthright art criticism (also Beuys-inspired) of Thai critic-curator-activist Thanom Chapakdee.

Each zone speaks of a network of concerns, unpacks small narratives. Yet the curatorial team’s suggestion that the MAIIAM collection embodies a ‘performative action’ – a remedial form of institutional critique à la Koh – also begs a broader hypothetical question: what errors, exactly, is ERRATA a response to? Within Thailand, MAIIAM currently stands alone as the only institution, public or private, with a readily accessible permanent collection of Thai contemporary art. Even the obvious contender, the national collection of the Thai government’s Office of Contemporary Art and Culture (exhibited earlier this year in a show that Bangkok Art Biennale director Apinan Poshyananda chided for offering ‘no trajectories’ and serving a ‘Thai-centric discourse’), still lacks a long-awaited home.

This line of conjecture is, however, moot: here is a nimble collaborative experiment in collection framing, not a show that traduces. Within the four walls of MAIIAM, it functions as a well-structured, scholarly foil to Feeling the 90s: the inaugural hang of its collection upstairs. Neither claims to be definitive. But whereas that instinctive and personal presentation of purely Thai artworks lacks context, and occludes both local dynamics and foreign influences, ERRATA proposes an overdue correction of sorts – a Thai art history that retraces the trajectory of Thai artists by intersecting with local, regional and global perspectives, by exploring and engendering entanglements that resist national framings and nationalist tropes.

ERRATA at MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, 30 July – 14 February