Bit Rot is an exhibition by the artist and novelist Douglas Coupland that took place at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam between 11 September and 3 January.This interview was done via email, a preferred medium when it comes to interviews for Coupland. Spread across eight rooms and a paperback book, Coupland, along with curators, Defne Ayas and Samuel Saelemakers, combines his own paintings, sculptures, photographs and texts as well as works from artists such as Jenny Holzer and James Rosenquist found in his collection. This interview circles the ideas behind a few select works from the exhibition.

HEMAN CHONG Let’s begin by talking about a text, specifically a sentence found in your show from Jenny Holzer. You have worked with Defne Ayas and Samuel Saelemakers to include works by other artists within your exhibition, with the result that this is your perspective: we are looking at what you are looking at. Holzer’s sentence, a Truism, cast in steel, says, ‘In a dream you saw a way to survive and you were full of joy.’ Can you talk about how this work functions within your universe of stuff, and why it’s in your collection?

DOUGLAS COUPLAND To begin with, the words themselves are lovely. They imply that as an artist you can imagine your way in and out of situations that seem, on a conscious level, unfixable. But these words can also apply to all people in all walks of life. They’re universal.

Holzer was a catalysing artist for me during the early 1980s. Some friends in art school returned from a trip to New York with ripped sheets of Truisms [1978–87] Holzer had put up around Soho. They really shocked me. This was long before the Internet, and it took ages for information to get from anywhere to anywhere. It was the first time I ever looked at words as raw art supplies. It was as if the ripped paper was dripping with truth. I doubt that I ever would have thought of writing had it not been for that moment.

Then in December of 1989 I was in Manhattan and saw Holzer’s Guggenheim show. The main work was very simple, a strip of red LEDs (then quite exotic) that cycled up three-and-a-half rungs of the Guggenheim’s helix, along which travelled a seemingly endless stream of Holzer’s Truisms. After about 45 minutes, something freaky happened, and the physical world dematerialised and I was suddenly inside what felt to be a universe of pure text, a perfect hybridisation of space and words – and then it ended. Fortunately I was there with a close friend, and she’d had the exact same experience at the same time – and it remains a strong bond between us. It wasn’t what I’d expected. It was a cherished moment of life on earth.

I wish I could have all of Holzer’s words cast in steel,but they cost money.I could only afford one, so I acquired this one, as it reminded me most about the texture of life during the 1980s. In my house I put it above my front door. It acts as a blessing every time you or me or anyone else walks beneath it. Also in the show is EXIT EVIL, a work located beside the fire escape, and THE FUTURE!, which is above an archway beside that same escape. I had no idea I was so superstitious about exitways until we began placing items, but that’s what collections teach you… tendencies you might have otherwise not seen.

HC And your David Bowie Death Mask, what are the relationships between that and the Holzer text?

DC The Holzer piece went above the David Bowie Death Mask. I was worried it might feel somehow sentimental, but I followed Samuel [Saelemakers]’s advice and trust that this isn’t the case.

I had now best explain how the Bowie piece came about, which is really convoluted, but I’ll try. I’m doing an ongoing sculpture project called Redheads in which the melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R) found on the 16th chromosome becomes a metaphor for small geographical locations to create new and unexpected mutations or even transmutations – think of wine and terroir, and the ability of extreme soil conditions to create unexpected wines. So I’ve been doing a long-term historical study of redheads, Bowie being one. I began collecting images and 3D approximations (when possible) of redheads through history, and I obtained the Bowie casting from an English makeup artist. That was about a year ago. But between then and now, a wonderful friend of mine, the artist Rex Ray in California, died of a hideous disease caused by smoking called Buerger’s disease. Rex had been David Bowie’s web designer for about a decade, and Rex had told me that it’s very, very hard for David Bowie, as a human being born in 1947, to be getting older – to be ageing within modernity, where every wrinkle and wart is scrutinised by endless cameras. I thought about it, and it has to be true. I remember in 1974, at the age of twelve-and-a-half, going to the Park Royal shopping mall in Vancouver and being scared shitless yet seduced by the huge poster for Diamond Dogs in the front window of a record store. In my mind Bowie will always be an androgynous twenty-four-and-a-half-year-old. And yet he’s not. He’s almost seventy. And this leads us to the great divide of the twenty-first century, which is the theological version of the ‘Jihad versus McWorld’ dichotomy: there’s no known system of thought that I can see that adequately reconciles the fact that with religion you have the afterlife, whereas with modernity, you only have the future. I think if Rex hadn’t died, this piece would never have come about. But Rex did die, and… it’s emotional. I miss him.

So to put Holzer’s words above Bowie’s facial casting, which has been proposed as a death mask, is like accelerating time and accelerating history, and laser-pinpoints the disparity between modernity and theology.

So… we’re almost at 900 words for one question. We’d best move on.

HC A thread that moves through your work, one that is evident in Bit Rot, is the idea that everyone is trying to make sense of the things around them in this completely subjective manner: that it’s impossible to define a kind of empirical way of talking about something like ‘fried chicken’.

DC I’m unsure if it’s apples and oranges to say the opposite of the search for personal subjective meaning is the search for empirical universal meaning. I think the opposite of the search for personal meaning is to not search for personal meaning.

We all surround ourselves with clues about ourselves everywhere, and if we search for them or think of personal clues as constellations, unexpected meaning will always emerge.

This sounds kind of old-fashioned, but I think it’s actually more about the future, more about pattern recognition. Back to [Marshall] McLuhan, who said that the one way to remain sane and stable in the midst of the maelstrom was to look for patterns. You may not find them, but the search itself will save you. Sometimes we look for personal patterns and sometimes, as with, say, the works about jumpers [Coupland’s Jumper series of World Trade Center works, 2013], it evolves into a universal revelation, and a universal horror, unleashing inside our heads all of those images we never discuss or process.

Empiricism is actually something I collect – a category known as ‘generica’ – objects that are the platonic absolutes of their category, sort of like the 3D versions of those supergeneric illustrations from twentieth-century encyclopaedias. I’ve attached a photo.

I also collect their cousin forms, which I’m unsure of the name: objects that look as if to be very precise and specific about what they are – we just don’t know what they are.

HC I want to point to the book Search |, which consists of search terms from Google, but also to The Living Internet [both 2015], which you describe as ‘a physical mockup in 3D of what the Internet and online searches actually look like. Can you talk a little about the context in which these two works are produced?

DC Since February I’ve been artist-in-residence at the Google Cultural Institute in Paris. One of the gists of my experience there was to contemplate how human beings search for something – anything – and to contemplate what that searching tells us about ourselves. Search | is derived from all global searches, February 2015, English language.

HC Why did you choose to make Search | into a book and The Living Internet as a kinetic sculpture?

DC Search |’s introduction explains its methodology, so I won’t go into that. But for The Living Internet (a terrible name, I know; I’m going to title its 2.0 version The Search Rodeo) I wanted to do something that wasn’t data visualisation. No pie charts. No charts of any sort. Just an anarchical, subjective snapshot of the chaos of raw searching, seen through my eyes. I mean, the Internet has no design. It’s not as if Tyler Brûlé came in and said, “There. I pronounce the Internet designed.” Its fluidity and transience is kind of breathtaking. I wanted the components of the piece to reflect this, so they’re built from trashy online 3D files, printed in a fleeting manner and then hurled into an arena to duke it out. The forms have glitches and damage and are actually evocative of the sloppy, lazy way people search. People rarely seek the meaning of life in Google (sometimes they do); they’re looking for acne cures, urban legends and videogaming cheats. It’s the opposite of noble, and it’s often very, very funny. I don’t know if you could depict the Internet without humour.

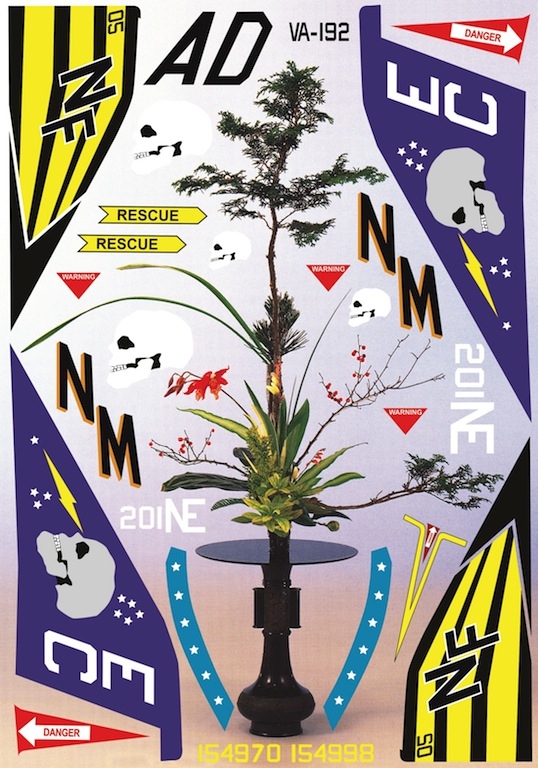

HC The collages within the Warflowers seem to embrace this sense of a search as well as a sense of placing two sets of misaligned imagery on a single plane; ikebana alongside military insignias. They remind me of flat sheets of stickers that contain die- cut graphics you might want to peel off and attach somewhere else. Can you tell us about how you came to think of these two things as a single image?

DC These pieces were done in 2006 as part of Toronto’s Contact photography festival. They’re very important to me for a number of reasons. I grew up in a military/air force gun-nut family, just like you see on TV: rifles and weapons on all of the walls that weren’t already covered with photos of my father in his jet. My brother is also a taxidermist, and over all of the flat surfaces were the insides and outsides of birds. My father also kept cattle out in the Fraser Valley [in British Columbia], and so there was an endless parade of meat for all meals and… I can’t believe I didn’t turn out to be Morrissey.

Growing up I hated all of this and vowed that when I could escape, I’d live in a place as opposite from it as I could – which is what I thought I’d done until Angela (yes, she of the Guggenheim) told me I’d done no such thing, and pointed out the F-111 piece (air force jet), Vietnam soldier (military + taxidermy), all of the death and disaster pieces, and… basically I’d just taken what I’d grown up with and reiterated it. I was so happy when she pointed this out, because I got rid of most everything that didn’t have to do with death or destruction and I could really focus on it specifically. I think that so much of what we find compelling in later life is what was lurid or frightening between the ages of eight to thirteen.

Ikebana: I went to art school in Japan in 1983. Part of it was that students had to take ikebana as part of the curriculum. As a way of learning about form and volume, I can think of few lessons more vital that way than ikebana. Anyway, my father always thought that the worst, most effete things you could have as an adult were vases… and so I took to ikebana like a duck to water, and now also have a collection of about 200 vases. Freud.

The pieces in the Warflower series are pseudo flat. It’s not really possible to see them as one integrated image. You’re either looking at the photo portion or you’re looking at the graphics, but both at once isn’t possible. Which is like me and my childhood. I hate art as therapy, but art as self-revelation is interesting. Look at Mike Kelley (who I never met; big regret).

Placing the soldier in relation to the F-111 is pretty much an embodiment of my relationship to my family and my past and my question of whether it really is possible to move forward or maybe it isn’t.

HC I spent last week (on a beach in Sagres, at the southwestern point of continental Europe) reading the new anthology of short stories and essays that you’ve published alongside your exhibition at Witte de With. The first book I read of yours was Microserfs, back in 1996, and reading Bit Rot last week really reminded me so much of how personal your writing is; that there is hardly a barrier to be scaled between the reader and yourself; that in fact you’re speaking to them in this intimate, confronting and gentle manner, much like receiving an email from a friend. I digress. My favourite story in Bit Rot is ‘Wonkr’, perhaps because it’s about an imaginary app (much like Oop!, in Microserfs) and the prospects of it existing in our world. I’m surprised that nobody has taken on what you’ve written in ‘Wonkr’ and made it a real app.

DC It’s only been out six weeks or so. Apps take forever to develop, but if someone has the correct assets on hand, they could become very rich very quickly. Minecraft (Oop!) just sold for over a billion dollars. But it’s kind of heartbreaking how many app-development companies there are out there – it’s like all the best-looking kids in high school going to Hollywood to get a screen test and become a star, and the chance is one in a zillion.

HC Have you ever considered making an app (or have you?) as an artwork?

DC Yoo [a fictional app, published in Bit Rot] began as an actual app-design art project – unironic and for real. Once I learned more about how search works, I could see why it would be not unfeasible, but… it would traverse too many e-domains to be practical.

HC Or maybe it’s more interesting to think of apps as something else (like a political platform) rather than an artwork?

DC No. I’d only like to do art-as-art apps. People who are too political are… well, if people get too political, it’s like when someone puts on country-and-western music and I suddenly feel a deep need to be anywhere on earth except there in the room having to listen to the country-and-western music. I get it, but I’m just not so into it.

This article was first published in ArtReview Asia, vol 4 no 1.