A new project presented at the Asia Pacific Triennial pieces together pre-colonial connections

Western history likes to imagine Australia as an island ‘discovered’ during the late eighteenth century by an intrepid group of British explorers. But Diane Moon has long been curious about the narratives that lie beyond this official version of events.

In 1983 she relocated from Sydney to Arnhem Land. It’s a place where beaches fringed by ochre clifftops overlook the Arafura Sea, a shimmering expanse of turquoise that connects the northeast tip of the country with its neighbours across the Indian Ocean. Here the traditional Indigenous custodians, the Yolngu, once traded with sailors from Macassar, a port city in South Sulawesi, part of the Indonesian archipelago. These communities forged a relationship that spans more than 400 years.

“I [learned about] lunggurrma, the cloud that heralded the Macassans’ annual arrival, [and] objects of trade including knives and swords, and [saw] the beautifully decorated poles representing the masts of the [Indonesian sailboats], or perahus,” says Moon, who resided in a community called Ramingining until 1984 and was based in Arnhem Land again between 1985 and 1994. She’s served as the curator of Indigenous fibre art at the Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in Brisbane since 2003.

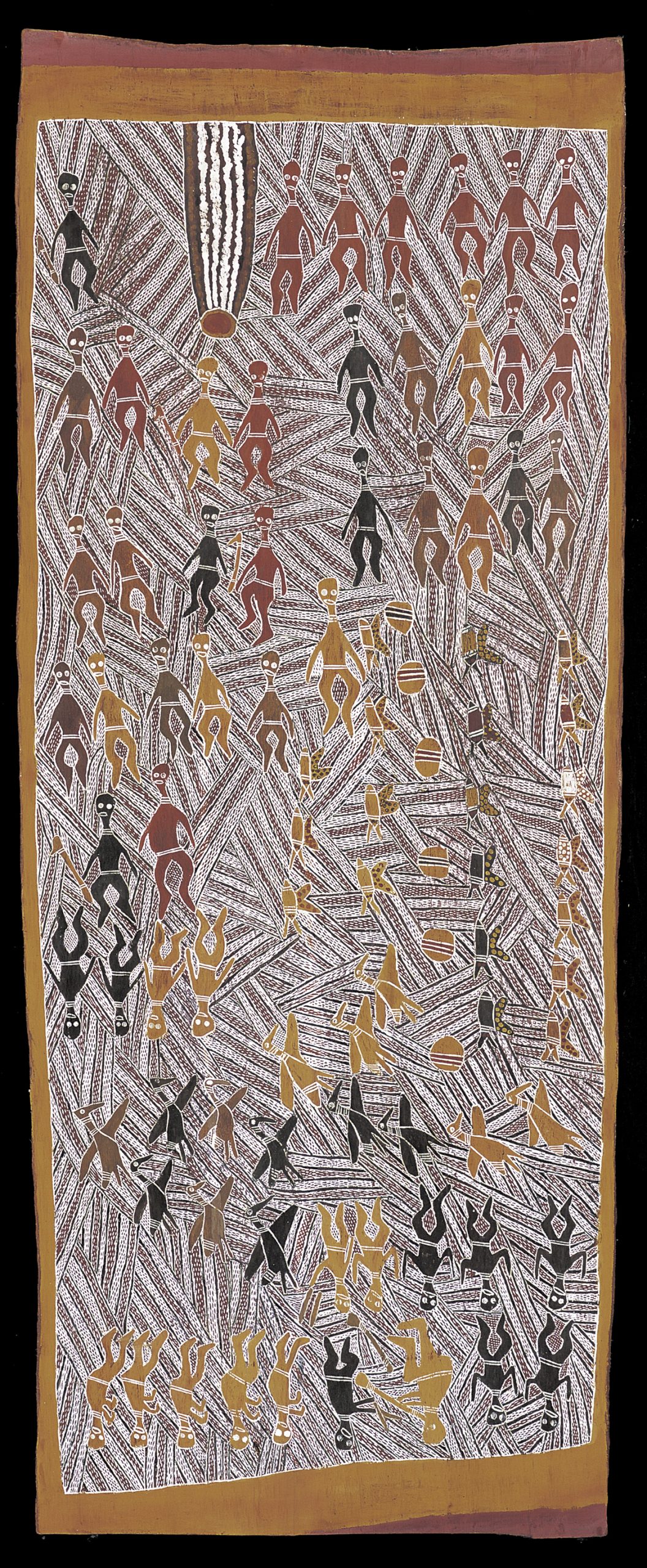

“In Arnhem Land, people made lipalipa, or dugout canoes, and sails [called] dhomala used to propel them,” she says. “Ways of working metal and rigging sails were introduced by the Macassans. Before Yolngu learnt to use these tools and techniques, they bartered for the wooden canoes, which allowed them to travel and hunt on the open seas. These are not just ‘stories’ but part of a real history that’s not widely known or taught.” Indeed, Moon has dedicated herself to exploring this relationship more deeply since she acquired a 1958 bark-painting for QAGOMA soon after starting there. Titled Balirlira and the Macassans, by the renowned Yolngu artist Larrtjanga Ganambarr, the work depicts the spirit man Balirlira interacting with the Macassans over five centuries, against a backdrop that owes its optical power to the Yolngu crosshatching, associated with specific sacred knowledge, known as rarrk.

It’s a journey that has led her to curate, working closely with Bugis artist Abdi Karya as cocurator, the Yolngu/Macassan Project, part of the tenth edition of the Asia Pacific Triennale (APT10).

Australia’s careful colonial calculus insists on a country shaped entirely by European settlement, a myth that erases 60,000 years of continuous Indigenous occupation, and one that also bypasses the histories of migration that have left their mark on this continent: the camel drivers who were brought by ship during the 1860s from countries like Afghanistan and Pakistan, to transport people and goods across the Outback until the 1920s; the hawkers and labourers from India who arrived in the late nineteenth century as British subjects, until the White Australia Policy, introduced in 1901, restricted nonwhite arrivals. And of course the Macassan traders, who started making voyages to Arnhem Land from the fifteenth century onward. These Muslim seafarers, many of whom belonged to the Bugis, the largest ethnic group in South Sulawesi, sailed to Australia on monsoonal winds each December. They lived for months alongside the Yolngu on local beaches, where they exchanged knowledge and oral and visual traditions, and worked together to source trepang, a sea cucumber prized by the Chinese.

The Yolngu/Macassan Project features works such as Dhomala (2019–20), a Macassan sail spun from woven pandanus and bark string by Margaret Rarru, a senior artist and master weaver. There’s Baine/Bayini, a 2021 video performance by Abdi Karya that explores the importance of cloth in Macassan and Yolngu society. It also includes a series of pots made in Sulawesi and painted by the late artist Nawurapu Wunungmurra in the zigzag patterns that belong to the Dhalwangu, a Yolngu clan group.

“A mutual respect developed between the Macassans and the Yolngu,” says Moon. “Importantly, they formed ‘family’ relationships, which meant [Macassans] were absorbed into Yolngu society with shared responsibilities and rights.” She adds that the Yolngu sometimes accompanied the Macassan back to Sulawesi, where they started families of their own.

But the project is less about an anthropological representation of history and more a celebration of the aesthetic culture these communities created together. “The room will be beautiful, with luminescent pale blue walls and mounds of pure white sand supporting ceramics and potsherds,” Moon says. “My hope, as always, is that the audience will gaze in wonder and appreciation at the work of Aboriginal artists.”

natural pigments on bark, 158 × 65 cm. © the artists. Courtesy QAGOMA, Brisbane

In 1906, five years after Federation, the new Australian government, under pressure from Christian missionary groups, banned trade between the Yolngu and the Macassan. Will Stubbs, the coordinator of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, an Indigenous-owned art centre in Yirrkala, a remote community in northeast Arnhem Land, has stumbled across fragments of Macassan pottery buried in the sands of Bawaka, a Yolngu homeland, for decades.

“The Yolngu have a nostalgic love for the Macassans and their relationship – they didn’t come on a boat to push people around like Europeans did, pretending to be nice and giving trinkets,” says Stubbs, who is a longtime member of the Yirrkala community and is married to a Yolngu woman. “They treated [the Yolngu] like their betters. The ban ravaged communities that were reliant on that trade. It caused complete economic collapse.”

Stubbs worked closely with Moon and Karya to realise the Yolngu/

Macassan Project. The Macassan pots that will be on show at APT10, he says, are a visual symbol of the relationship. “In the course of making the pots, I’ve been sending them to Sulawesi and back,” says Stubbs. “They have been broken and rudely fixed, but we are embracing the parts. The pots are also symbolic of repair.”

The presence of Macassan culture among the Yolngu, says Stubbs, isn’t limited to material fragments. Balanda, the Yolngu word for European or outsider, stems from the Macassan word for ‘Dutch’ or ‘Hollander’. Yolngu song lines riff on Bugis creation myths that may no longer be voiced in their place of origin. Stubbs tells me the story of Gunybi Ganambarr, a Yolngu artist from the Dhuwa moiety, whose car broke down while he and family members were hunting for turtles. Abandoning the car for a small boat, they sewed their shirts together to form a Macassan sail and were eventually found by a police boat on the lookout for the missing family. He depicts the sail in Djirrit (2021), an intricate work on etched aluminium, on show at APT10. “Gunybi is such a powerful artist – not only can he get you out of a life-threatening situation with his genius, but he can make an incredible artwork showing you that scene in a completely new way,” he says. “The contemporaneous presence of the Macassan actually saves his life.”

Stubbs believes that the story of the Macassan in Australia is also a story of cultural exchange that’s long predated white Australia. “It is very inconvenient for the Anglo-Australian project to understand that they are not the second-longest occupants of the continent but the third,” Stubbs says. “It’s completely to do with the European notion that history only happens when a white person is present.”

The story of the Macassan and the Yolngu is also an antidote to an Australia that polices its borders and too often regards its conversations with Southeast Asia as a new phenomenon – rather than a centuries-old connection rooted not just in mutual geography but in profound cultural ties. “Every other civil society in the world has embedded into an understanding of itself that there is a group of people who may look different and talk different,” he says. “The history of Australia is the history of human beings on the continent. It has been embedded in our mind to start history at a random point, whether it is 1770 or 1778. And that is a deeply flawed approach.”

The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT10), including the Yolngu/Macassan Project, is on view at Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 4 December – 28 April

Neha Kale is a writer and editor based in Sydney

From the Winter 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia