Using images sourced from colonial archives, film, fashion and family albums, the artist carves representation and empowerment from stereotype

‘There is no set of years in which to be born Black and woman would not be met with violence,’ states Christina Sharpe in her book Ordinary Notes (2023). Having read these words shortly before visiting Frida Orupabo’s latest exhibition, I find the writer’s concise assessment of the historical injustices done to Black women reflected in the Norwegian-Nigerian artist and sociologist’s chimeric and confronting photographic collages.

Sharpe’s single sentence comprises Note 232. The book as a whole is made up of 248 texts of various lengths that take – in part – art, literature, mass media, memorials and historical and recent events as points of departure from which to consider the complexities of the Black experience (primarily in the US), while addressing the issue of ‘who gets to tell the story of the African diaspora’. It strikes me how its structure is much like a collage; and much like the way in Orupabo’s work contorted female bodies are made up of cut-out scans of photos from colonial archives, film, fashion, art and family albums.

Orupabo mines the internet for the source images and pieces of footage that are later incorporated into the collages, publishing a fraction of her findings into her own digital archive of collected material under the Instagram handle @nemipeba. It also includes wide-ranging visual references to artworks including those by Grada Kilomba, Carrie Mae Weems and Kara Walker, stills of films, including Blacula (1972), images from university library photo-collections, clips of singers including Nina Simone, Billie Holiday and Barbara Lynn, and footage of firsthand accounts of racism. The finished collages are formed by multiple layers of these scans and pinned together with metal tacks so that they resemble pantin dolls; seemingly manipulable female forms.

Born to a white Norwegian mother and a Black Nigerian father, Orupabo grew up in Sarpsborg, a small city with, like all of Norway, a predominantly white population. For Orupabo, who is nominated for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize this year, personal experiences of racism and a feeling of invisibility are also inextricably bound to the social and cultural contexts of the African diasporic experience. “The representation was not there,” says Orupabo, referring, in a 2022 interview published by Louisiana Museum’s video platform, to the lack of Black visibility in the different forms of mass media and education that she encountered while growing up. The few representations she did find were most often “racialised and [or] sexualised”. “I was very aware of the power of images,” she says. “For me, to create work that looks back at the viewer is a way to refuse to be made into an object, and to say, ‘I see you’.”

A hard stare emanates from Two Heads (2022). This photographic portrait of a woman, her brow furrowed, is mirrored by an exact copy attached upside-down at the neck. In keeping with all of Orupabo’s works, the source of the original image is not revealed, but it recalls the style of photographs taken by nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century anthropologists like Northcote W. Thomas, who was appointed by the British government to document the ‘physical types’ of West African people for the Colonial Office. Thomas’s anthropometric photographs, recorded between 1909 and 1915, contributed to the stereotyping of African communities on the basis of physical attributes. The photos were disseminated among British government administrations as a means of ‘proving’ their inferiority – and therefore suitable for continued subjugation by ‘superior’ colonists. This objectifying practice via photography finds its roots in the earlier 1850 series of slave daguerreotypes commissioned by Swiss-American biologist Louis Agassiz, whose ‘scientific’ application of taxonomic traits paved the foundations for historical racism – on which much of today’s anti-Black racism stands. Orupabo’s work reckons with this loaded history of representation and misrepresentation.

Here, Note 184 of Ordinary Notes comes to mind, a contribution from Black feminist theorist Tina Campt (one of several writers and thinkers Sharpe called upon to help create a ‘Dictionary of Untranslatable Blackness’ that weaves its way through the book) on the concept of the ‘gaze’: ‘A Black gaze challenges us to embrace the affective labor of grappling with uncomfortable gaps between proximity and protectedness and in doing so, opens up the possibility of a future lived otherwise’. Coming into proximity with Two Heads raises questions of difference between the acts of ‘gazing’ and, as Orupabo emphasised, ‘seeing’. The direct stare of the anonymous woman in the photo challenges the viewer’s gaze, which in an exhibition setting typically comes from a protected and distanced position of observation. Perhaps to really see this woman in the photograph is to ask: who is she? Who is taking her photograph? Under what conditions is her image being taken? How does this make her feel? And how would her presence in this transfigured, mutant artwork make her feel? In this context, the shift between ‘gazing’ and ‘seeing’ requires of the viewer an engagement not only with the portrait as an artwork but as a portrait of a person whose experience of being photographed is located in the real world.

Hostile stares pierce through many of Orupabo’s collages, particularly those that most straightforwardly deal with Black female sexuality and objectification. Three Legged Woman (2022), for example, a work currently on show at Modern Art in London, presents a naked, reclining white female body (above it Eye, 2022, is installed; this collage of an eye, the space of its iris and pupil filled by the partial profile of a Black woman, offers another reference to the ‘gaze’). Two legs are bent towards the viewer, while a third, stockinged leg is raised to create an open, sexually suggestive pose; attached to the body is the head of a Black woman who is frowning at the viewer. Paper-pinned at various points of her body, the limbs of the woman look as if they might be moveable. Orupabo employs the use of pins throughout her works, which are not only suggestive of the ways in which the female body has (and continues to be) seen as an object to be manipulated, but that action of pinning many-layered images emphasises how, historically, certain racial representations of Black women have been reinforced.

Despite the initial suggestion of sexual availability, the Three Legged Woman’s countenance indicates otherwise. Two of the legs remain knees-locked, in a final closed-off position; she’s in control here. That sense of reclaiming the power to choose how a woman’s body, and more specifically Black female sexuality, is presented and received is a central theme of Orupabo’s work; in part fuelled by the artist’s own anger (to which she alludes in the Louisiana video) at the simultaneous indignity of racialised images of Black women and the lack of positive representation. It’s an anger that is multilayered and expressed by Audre Lorde in Sister Outsider (1984), a collection of the writer and poet’s essays and speeches that explore race, sexuality and female solidarity: ‘Women responding to racism means women responding to anger; the anger of exclusion, of unquestioned privilege, of racial distortions, of silence, ill-use, stereotyping, defensiveness, misnaming, betrayal, and co-optation’.

Orupabo’s works are reminiscent of vintage paper fashion dolls, onto which paper cutouts of the latest fashionable outfit could be attached to the figure of, typically, a pretty, white woman. The first Black paper doll to be mass-produced in the US (in 1863, the year of the Emancipation Proclamation) was modelled after Topsy, a character from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Though considered an Abolitionist novel, Stowe’s characterisation of Topsy – as an ‘odd and goblin-like’ ‘specimen’ with ‘woolly hair’ – also led to the reinforcement of racial stereotypes. While projecting Black female visibility in her collages, Orupabo’s incorporation of white torsos, breasts, arms and legs adds further complexity to Western ideas of what is considered a ‘desirable’ body: here, instead of the application of clothing, is white skin.

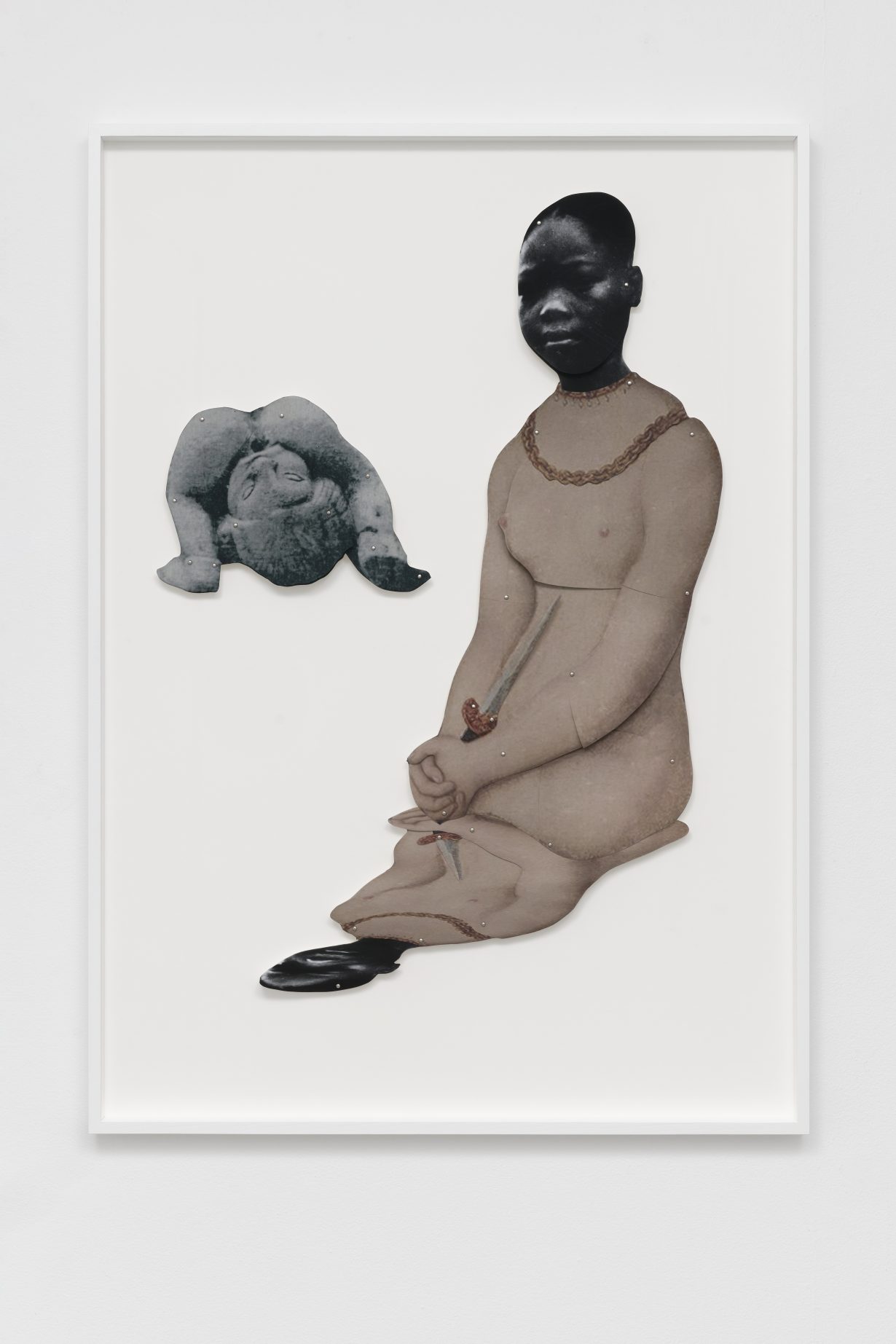

In Woman with knife (2022), Orupabo takes a digital copy of Lucas Cranach the Elder’s painting Lucretia (1526–27), cuts the naked white female body out of the original image (a Renaissance example of the feminine ideal: smooth alabaster skin and golden hair that signified health and purity) and pieces it back together with the head of a young Black woman. She looks impassively back at the viewer, the knife held between her hands pointing towards her ribcage but not yet piercing flesh; to the left of the female body Orupabo adds a collage of a stone figure, which squats in a rolled up, legs-over-head position. The story of Lucretia, a Roman noblewoman who was celebrated for her virtue, loyalty and beauty, and who was raped and subsequently killed herself to preserve her ‘honour’, was historically used as a tale of morality for European audiences. Woman with knife, by contrast, calls into question the brutality of honour suicides and killings, the disposability of women’s bodies and the exclusionary nature of Western beauty ideals reinforced by art historical paintings. It also, perhaps, alludes to the colonial rape of occupied African countries.

Cutting up images, revealing the violence done to Black women’s bodies, and pinning them back together to form new representations and contexts, Orupabo explains in the Louisiana video, is “like you want to rip everything away that has made you feel invisible, and force your way in… I had the need to manipulate reality – to create my own narrative”. Labour I (2020) and Baby in belly (2020) are each collages of a different woman lying horizontally. The former is made up of black-and-white images: a young girl’s face layered over the top of the head of what looks to be a pornographic photo of a bare-breasted woman. She is partially clothed, with one stockinged leg and a cut-out piece of rumpled fabric Orupabo has pinned to her torso. A baby’s head emerges from her vagina. In Baby in belly the woman’s body is again made up of parts from different photographic sources: a huge pink ‘womb’ takes up the space of her abdomen, elongating it, and inside which a photograph of a seemingly already-born baby is pinned. A pair of high heels lie by the feet of the mother; an allusion to the ever-present pressure to work, while actually in labour, perhaps. The expressions on the mothers’ faces are inscrutable. There is a physical violence in these images, in the splitting of the Black female body, that recalls notoriously cruel incidents of scientific experimentation on Black bodies, including that of American physician J. Marion Sims, who, Sharpe writes in Note 62, ‘tortured many enslaved women – among them Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsy, to call just three of these women by their names – by performing multiple surgeries on them as he experimented for a way to cure vaginal fistulas. It goes without saying that these women were unable to consent. Sims carried out these surgeries without the use of readily available anaesthesia.’ And yet, for all the violent references to historical injustices against and violations of Black female bodies, Orupabo’s reconstructions also picture transformation and renewal, birthing hope for the next generation of Black lives.

For the artist, manipulating reality and transformation also takes the occasional form of human-animal hybrids. In the Deutsche Börse Prize exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery in London, Batwoman (2021) appears pinned to the wall: an archival photo of a woman’s head is attached to black outspread ‘wings’. In Untitled (Spider II) (2022, which was on show at Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town last year), a woman’s head sits atop a white spiderlike form. Both of these works appear to allude to West African folkloric traditions: the former a nod to witchcraft practices, in which bats are considered evil spirits or indeed witches themselves, while the latter speaks to tales of Anansi, the god of wisdom and trickery, who is often depicted in spider form and who, via stories carried across the world by the Atlantic slave trade, became a symbol of slave resistance. In these works, there’s a sense that Orupabo upends the racist agendas of colonial images by presenting hybrid female forms as images of empowerment. Here, in this reconfigured state, these people are unknowingly drawn from the archive towards finding “joy”, as she says, “in creating new realities and new identities”. In the destruction of the stereotype, Orupabo reconstructs new narratives that centre around, as Campt put it, the ‘possibility of a future lived otherwise’.

A solo exhibition of work by Frida Orupabo, Things I saw at night, is on view at Modern Art, London, through 20 May; work by Orupabo can also be seen in the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, through 11 June