The New Delhi-based artist draws attention to the moments when pieces of natural history are extracted and transported to museum collections – to be consumed as curios

Museums are odd places. They often conceal more than the various histories they reveal. The sparse information on provenance and dates below displayed objects sanitises the journeys they were forced to make from their homes to vitrines, drawers and storage rooms in buildings around the world. Not surprising, for such migrations were almost always marked by the violence, trauma and exploitation of colonialism.

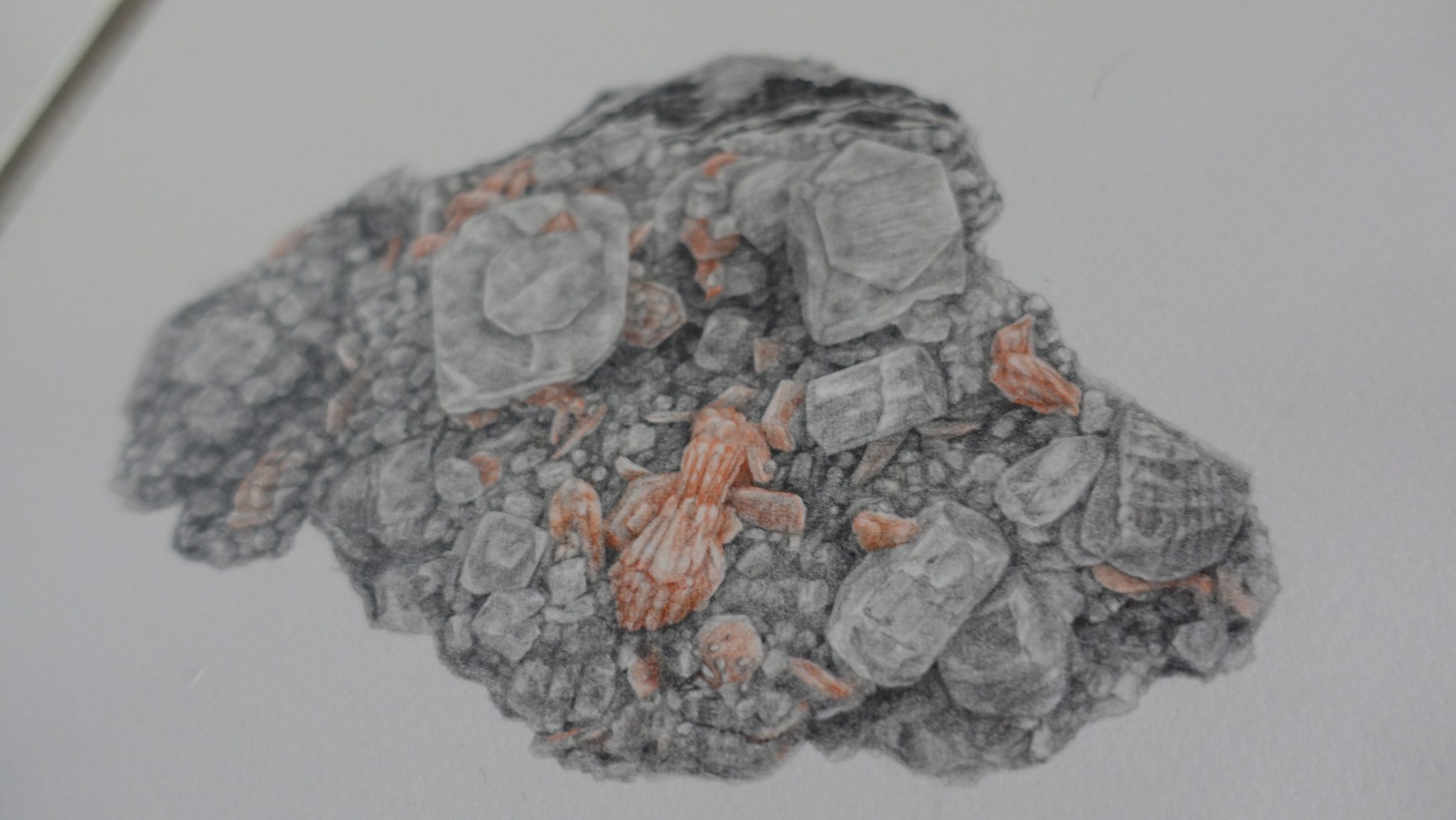

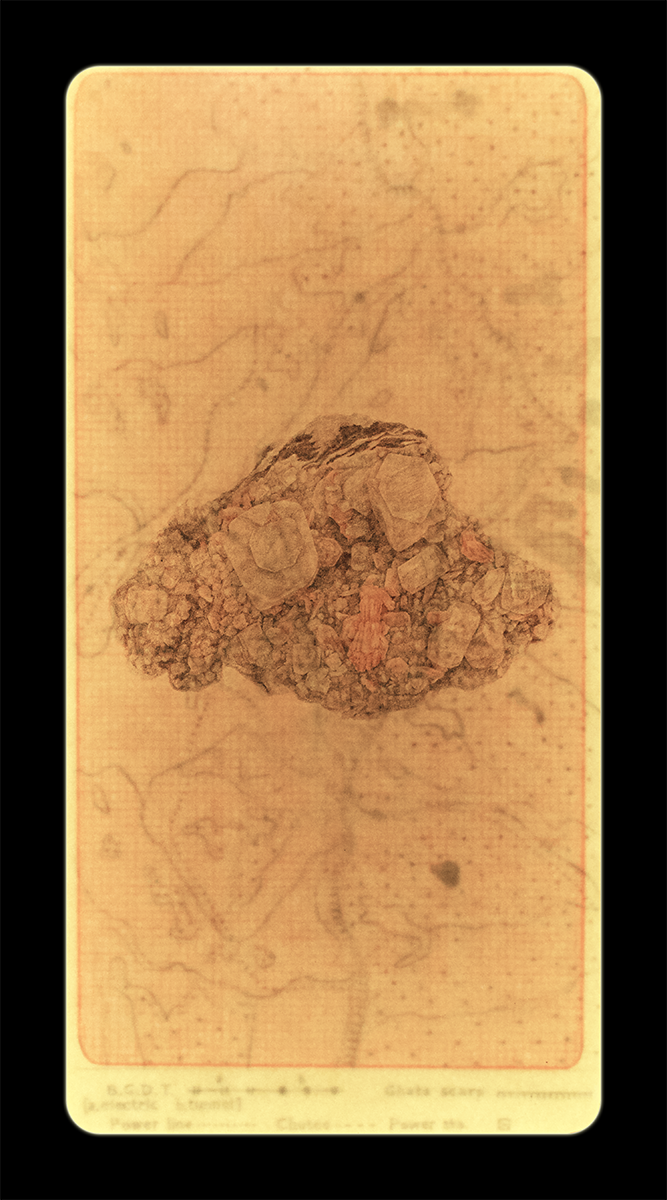

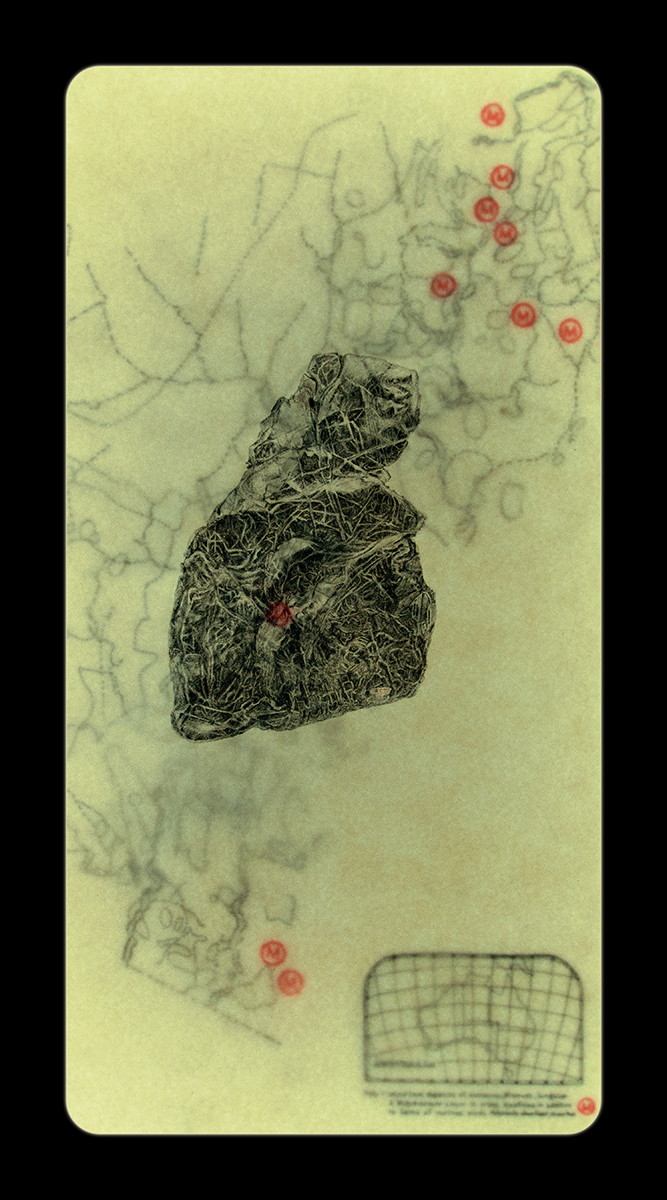

Garima Gupta’s recent work Out of Place (2021), which the New Delhi-based researcher and artist posted online over a few months – she and I follow each other on Instagram – draws attention to the moments when pieces of natural history were separated by excavation from a mountain, river or cave and transported to museum collections to create a visual inventory of nature to be consumed as a curio. What was to be an onsite residency shifted to Zoom because of the pandemic, and Gupta worked mostly with archival images. The drawings in the series take the minerals and meteoritics in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art in Connecticut as a starting point to comment on the difficult histories behind such acquisitions. Importantly, her work recontextualises the presence of such materials in these ‘out of place’ collections, so far away from their sites of origin. They resonate with the current reckoning of museums in the global north with the weight of colonial pasts and issues of reparation and restitution of objects in their collections.

Researched in collaboration with curator Chitra Ramalingam, Gupta’s drawings layer images of minerals over aspects of their history. For instance, the apophyllite is from Bhor Ghat, a mountain pass near the port city of Mumbai that was tunnelled by British colonialists to lay one of the first railway tracks on the subcontinent. It was a project that notoriously resulted in the death of thousands of workers due to poor working conditions and several epidemics. Gupta inserts an archival image of the first railway map under her drawing of the mineral. The map does not seem very detailed; in fact at first it scarcely even looks like a map. But the hint of a backstory to the mineral drawn in the foreground is an invitation to the viewer to imagine a landscape that places the museified object in its natural, native setting and highlights the extractive process that led to its presence in the museum. In another work in the series, she draws an image of a part of a meteorite that fell in Namibia centuries ago, the specimen from another world now labelled and in a museum. There are also drawings of graphite, calcite, copper and molybdenite, all of which continue to be of value in commerce.

Obviously, the idea of extracting resources from nature, mostly by force, and unmindful of the larger sociocultural and political implications this carries, is hardly a modern-day problem alone, as it can be traced back to the early decades of European colonial ambitions.

Native populations that lived with the earth and not as a separate, more powerful entity to it, were routinely branded wild and primitive, and therefore ‘eliminated’, ‘tamed’ and ‘civilised’. The use of such associative language aided the perception of alienation between the natural world and us human beings. One of the many repercussions of this distancing was that parts of the earth were routinely and crassly removed to be exploited, whether industrially or by museums, passing through networks of power, inequalities, value, caste and other layers of politics.

The exploitation and trauma evoked by museifying nature (leaving aside cultural, spiritual and historical objects of importance for now) is hardly an abomination from times bygone. Especially in countries like India, where a capitalist economy was introduced later than in Anglo-Euro-America-centric societies, the practices of colonial pursuits continue, with projects that bulldoze people’s desires and the landscape’s capacity to tolerate such change.

Just in my district of Kodagu alone – a tiny principality set in the Western Ghats mountain range of Southwestern India – deforestation and unchecked construction projects have led to erratic weather patterns that result in floods and landslides. A class of climate refugee is slowly being created. Support to the economy comes from a newish tourism industry, but uncontrolled development in the sector has brought another set of socioeconomic and cultural problems for these vulnerable hills. Yet, against common sense and science, a flyover project to the hills where the river Kaveri is born – a site that saw several kilometre-long landslides just last year – is supposedly in the offing. A heli-tourism project newly begun will not only disturb precious wildlife but also contribute to a surge in more construction to accommodate the tourist influx. Animal–human conflicts caused by shrinking forests are at an all-time high. Nationally, new amendments to a mining bill will make it easier for companies to bid for and control mining rights in the country, further privatising the commons. Such instances of brazen, shortsighted exploitation of land are innumerable, but hardly feature in mainstream media, which so often toe the Modi government’s line.

Gupta’s works serve to newly draw attention to how the colonial mindset continues in the modern world, albeit cloaked as capitalism. Most artefacts and natural materials in museums everywhere will likely remain migrants that can never return home. As a means to understanding how a country’s resources are ruthlessly plundered, often in cahoots with the government itself, Gupta’s drawings reveal the absurdity of the very act of collecting parts of nature and the violence involved in such practices.

Deepa Bhasthi is a writer based in Kodagu

From the December 2021 issue of ArtReview