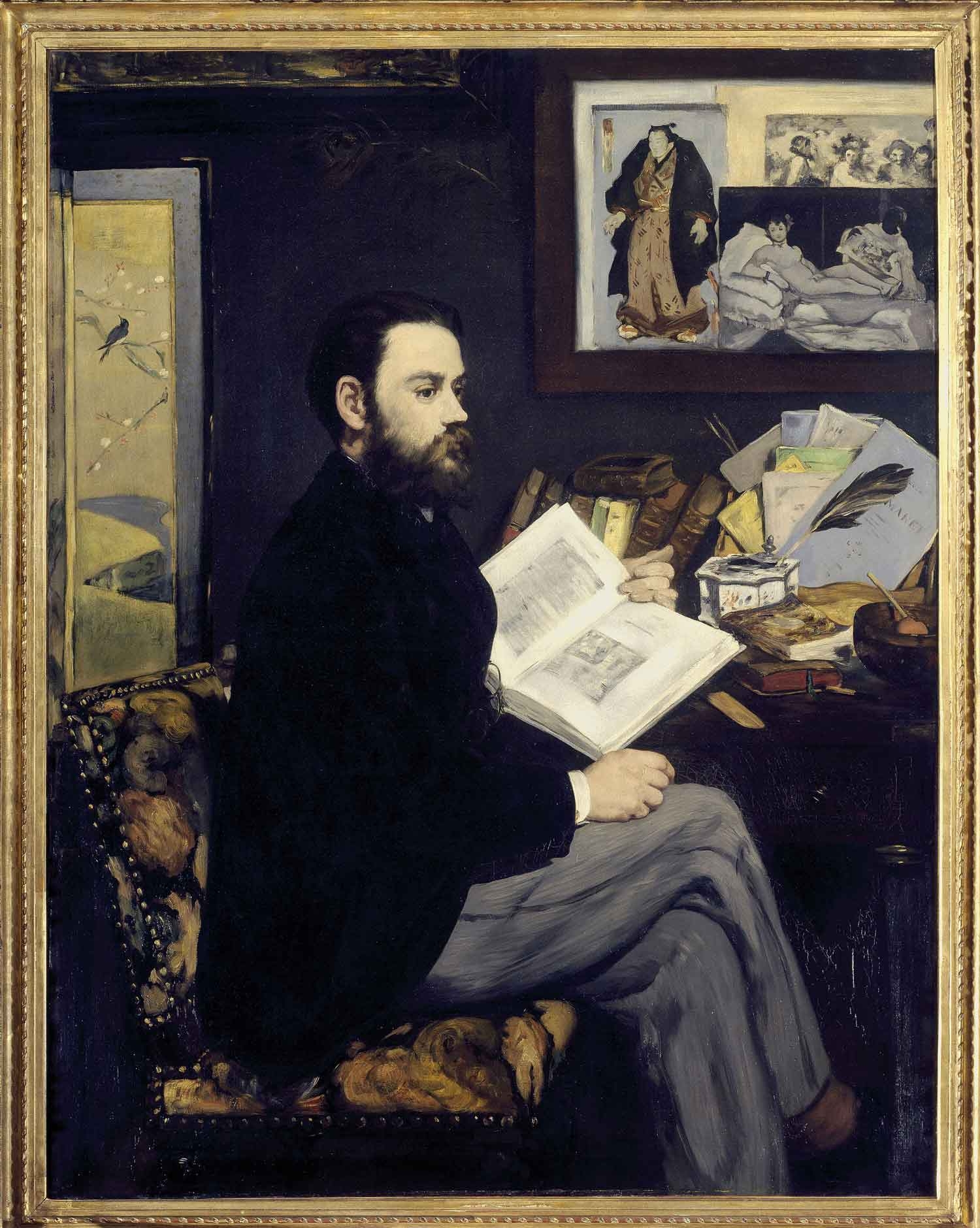

Émile Zola (born in Paris in 1840, died 1902) is known for his public defence of the works of Manet when this artist was the subject of ridicule, for his campaign of liberalism during the Dreyfus scandal (when a Jewish artillery officer in the French army was wrongly imprisoned for spying) and for his series of novels describing the history of a family under the Second Empire. One of these is a thinly disguised portrait of Zola’s childhood friend, the painter Paul Cézanne.

ARTREVIEW

What is realism?

Émile Zola

In Courbet’s paintings of the mid- 1850s you find down-to-earth scenes. At the time they were interpreted as socialist, communist, bohemian and avant-garde, but also ‘realist’, all relatively new terms. Previously, from Brueghel onwards, scenes of peasants returning from work or entertaining themselves at the end of the day with music were small and patronising. Now the downtrodden had a place in visual art that was epic and challenging. Thirty years later my books were thought of as the literary equivalent. The term I invented for them, as a logical extension of realism, was ‘naturalism’. I meant something particular by it: character and personality are shaped by history, and there are no individual heroes who transcend history.

Is realism always right?

EZ In the twentieth century realism lost its clarity as a buzzword. In the 1910s something in literature could be ‘real’ because it was experimental, like the way thoughts really flow, or reality is really perceived, but at the same time it might be unlike what most people really wanted to read. Art insisted on stripping away artifice. But the representation of reality requires certain pillars of artifice, it turned out: a narrative, a coherent voice and a graspable theme, plus pleasure rather than pain. By the

1930s the term had virtually become a way of saying: ‘lacks sophistication’. In totalitarian societies the authorities violently demanded that it should. Elsewhere lack of sophistication was achieved naturally and accompanied by a combination of guilt and triumph. Today art has a hunger for reality, but the ‘real’ might be a penetration of the veil of illusion that consumerism generates or, alternatively, any one of a vast range of sinister sub-illusions issuing from the same source.

You wrote a book featuring a character called Claude Lantier, who is supposed to be Cézanne: is it a true picture of his biography? And are his brushstrokes realistic?

EZ You have to remember that Cézanne, like Julius Caesar, has no biography apart from textual reconstructions. And the book you refer to, L’Oeuvre, whose English translation is called The Masterpiece, is a key source in any biographer’s conception of the life of Cézanne. They look for proof to validate ideas about his personality that they initially acquired from my novel, whose central protagonist is an artist bent on self-destruction.

I’m not sure that answers the question.

EZ Well, another thing to bear in mind is that novelists are seldom much good at getting the tone of art. You only have to think of the unhelpful sentimentalism that Colm Tóibín, Siri Hustvedt and John Updike advocate as art commentary, which is swallowed by a middle class audience grateful for relief from the boredom of the serious. Those writers treat art as a holiday from their real work. However, the world of art has a logical place in my work. The Masterpiece is part of a novel sequence, consisting of 20 volumes, in which I look at the influences of inherited traits and environment on a single family over several decades, culminating in the period of the Second Empire. For the purpose of the work as a whole – the driving concept of all the books – I needed my central character in The Masterpiece to be an emotional wreck, and his paintings, which ought to celebrate life, to be dismally incoherent. He is the child of alcoholics. Alcohol’s influence is a deadly theme throughout these novels. It’s to do with bad blood. But it leads to all sorts of scenarios, some curiously ambivalent. In L’Assommoir, for example, a wedding party of drunken working people, including Claude Lantier’s mother at a young age, goes round the Louvre. They’re seeing the paintings for the first time. As the reader you see them too through their eyes. It’s like a mad pantomime. You’re shocked by the change from one world to another, and somehow originality itself becomes highlighted. Anyway, this is one group of workers. In Germinal I follow the lives of another: coal miners. And in The Masterpiece it’s artists. Not just Cézanne, but also Manet and Monet, as well as lesser figures. These literary representations of different sectors of society are constructed from fragments of experience and research. No character from real life features in an untransformed way. Lantier’s first painting in The Masterpiece, for example, is not based on anything by Cézanne but on Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. So, as for truth, there is no answer. After all, who are you, Matthew? Who made you up?

Oh yeah, I see what you mean. Gosh, that is a thought! Well, in relation to realism, what is the point of the myth of Cézanne as a ‘primitive’?

EZ As you say, it’s a myth. Cézanne’s pose of hopeless country bluntness when he had to negotiate art circles in Paris, where you get these tales of him refusing to shake hands with Manet – on the grounds that ‘I haven’t washed for a week!’ – was based on social unease caused by neurosis, not simplicity. He was the most educated major painter of his time. He haunted the Louvre. What he does with painting, with his juddering contours, discontinuous surfaces, rhythmic structures, complex balance of contrasting and harmonious colours, as well as his repetitive broken mark, which you referred to earlier, is a kind of art that not only looks for its bearings in ‘art’ but also constitutes a profound philosophical comment on it, in that it says that art is fundamentally about seeing, about perception. His brushstroke diminishes everything else, it diminishes ‘the world’ as authority and emphasises instead apprehending the world. Apprehension itself, this mental abstraction, is made into a concrete thing, concrete matter: Cézanne’s surfaces that tell you about sensations, fragmentary glimpses, but little else.

Wow, that’s lyrical! You can see why people love him!

EZ I don’t think they do any more. I used to say he was sincere but misguided. However, a consensus builds, and it is impossible merely to express an opinion about Cézanne today: I like him; I don’t like him. This would just be ignorance. It’s confusing because the fact is that the consensus has all but evaporated. People today, and this certainly doesn’t exclude art people, do tend to see him as the Moses of a baffling Modernism. Ignorance does indeed reign. He is avoided because he is considered cold, intellectual and intangible. But when he first began to be regarded as more than an obscure provincial, which was the 1890s, he was celebrated as passionate, sensual and rooted in the earth.

But everyone knows who he is, surely?

EZ The art audience today is entertained by picture books showing colour photos of his sites, with his paintings alongside. They say, ‘Ah, he really gets the colours of the area around Aix-en-Provence!’ But they see this kind of thing as compensation for a lack of clarity. They move on to paintings by artists they like that actually look like photos. They feel nothing but relief when someone in the papers who’s been given the joke title ‘art critic’ announces that Cézanne suffered from failing eyesight, that he was too arrogant to get new glasses, he really couldn’t do verticals because he was half blind, he always did them ‘on the tilt’ and so on. While pretending to deplore reactionary views, the audience secretly believes in the truth of what it says in the London Evening Standard. You’d think this was the old aunties and the mums and dads: the straights. But I’m always amazed at how artists believe it too – quite famous ones. They don’t question it, because it’s a matter they rarely think about anyway. It’s great social material, actually. If I were still alive I’d put it into a novel.

You mentioned politics, how does that work with Cézanne?

EZ Again, it’s not straightforward. He was an anti-Dreyfusard. He didn’t shout about it and make pronouncements, as Degas and Renoir did, his fellow anti-Semites. But he was a political reactionary for sure. As the author of J’accuse!, my exposé of hypocrisy, I’m on the other side of the political fence to him. But artistically he is far from conservative. His paintings of a natural order, which appear to be making themselves anew every time you look, are a profound allegory in visual form for a political attitude. You are forced to put reality together for yourself in a fresh way, as he has put it together for himself. You must accept that no one owns the truth. Rather, we speculate, and we constantly create.

What about politics and art nowadays? How about student fees in the UK?

EZ It’s only right to object to them being too high. Politics is always about ideals whose purpose is to change reality. So all students should have a political consciousness. They should be aware of the issues and they should join in the demonstrations. The other subtler issues have to come after the more obvious black and white ones.

What do you think are the subtle ones?

EZ Well, art schools have become questionable institutions. You imbibe platitudes that come from a bottomless well of diluted maxims originating in deconstruction. Over the years deconstruction has ossified into a creed, and its ethos, which used to be always to search for more in any situation than many people believe is really there, has reversed. Now it is about always settling for less. Seeing art history as mere ideology is only one example. Cézanne wasn’t childish, but this is exactly the degenerated mental state that present-day art culture, as it is passed on at the education level, demands. Needy posturing. Childish emoting. Art critics on The Guardian, or authorities on culture programmes on TV and the radio, are all too willing to ratify your bullshit and be childish themselves. I think it is a political matter to reform art schools, just as it is political to fight for free entry to them.