In Mary Shelley’s time, science and technoculture set their standards against magic. Who – or what – is our Frankenstein today?

Guillermo del Toro is using his Frankenstein press tour to spread the anti-AI gospel. After a Halloween screening and Q&A session for his latest film, del Toro roused the crowd at Los Angeles’s Chinese Theatre to join him in chanting, “fuck AI!” The Mexican director, known for directing quirky blockbusters like Hellboy (2004) and Pacific Rim (2013) and auteuring horror fairy tales like Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), has never been shy about expressing his disdain for AI-generated ‘art’, as he refuses to call it. In a 2024 talk at the BFI in London, the filmmaker described generative AI as a tool with a demonstrable ability to create “semi-compelling screensavers”. In 2022, he was asked about generative AI’s possible incursions into film, and he cited Hayao Miyazaki in calling it “an insult to life itself”. More recently, he told NPR that “I am not interested, nor will I ever be interested” in working with generative AI, adding that, “I’d rather die,” than do so.

In both his work and his commentary, del Toro has balked at Enlightenment hubris all while marveling at human innovation with fearful delight. His films often tell stories of monsters that push through the tectonic gaps between magic and science, superstition and enlightenment, mysticism and reason. The ghosts of Crimson Peak (2015) spoke through letters and wax cylinders. The Shape of Water (2017) is set in a high-security government laboratory. And his adaptation of ‘The Modern Prometheus’ has proven to be no different.

In his deviations from Mary Shelley’s novel, del Toro embellishes the story with vignettes that spotlight nineteenth century technoculture: Oscar Isaac’s Victor Frankenstein builds his creature in an abandoned water tower that’s furnished with the latest and greatest in medical and electrical tech made by Henrich Harlander (Christoph Walz), an arms manufacturer who will spare no expense in his quest for life-giving technologies. The Creature’s animation scene, which Shelley is careful to describe only indirectly, is here an epic display of technological theatre: a symphony of machines and hydraulic mechanisms gurgle to life as Victor runs around the lab frantically, pulling levers and tending to steaming valves; a claw of silver prongs arch through the air and opens to pour a stream of lightning into a crucified figure made of body parts harvested from hanged criminals and Crimean War casualties.

Steam, electricity and anatomy are, of course, near requirements for any Frankenstein screen adaptation. But del Toro’s choice to push the plot a few decades into the future to coincide with the Crimean War is not a subtle one. Dubbed a ‘theatre of exuberant technological enterprise’ by one historian, the conflict that saw the Concert of Europe imperilled by Russian expansionism ‘became a stage for the display of innovative technologies ranging from telegraphy to photography, railways to steamships, and ironclads to sanitary hospitals.’

Harlander doesn’t just invest in emerging technologies but collects and plays with them too. He follows Victor around his lab with a camera that uses a wet collodion process, a fresh 1851 invention that would, we can guess, not have been more than five years old. In another scene, he shows Victor what he claims is the fifth Evelyn Table (the oldest anatomical preparations in Europe, of which there are in fact only four, housed at the UK’s Hunterian Museum). The fictional fifth, he explains, is of the lymphatic system, a realisation that proves instrumental in Victor’s project, and one could imagine, would be able to offer humankind much more if it weren’t shut away in a war profiteer’s private collection.

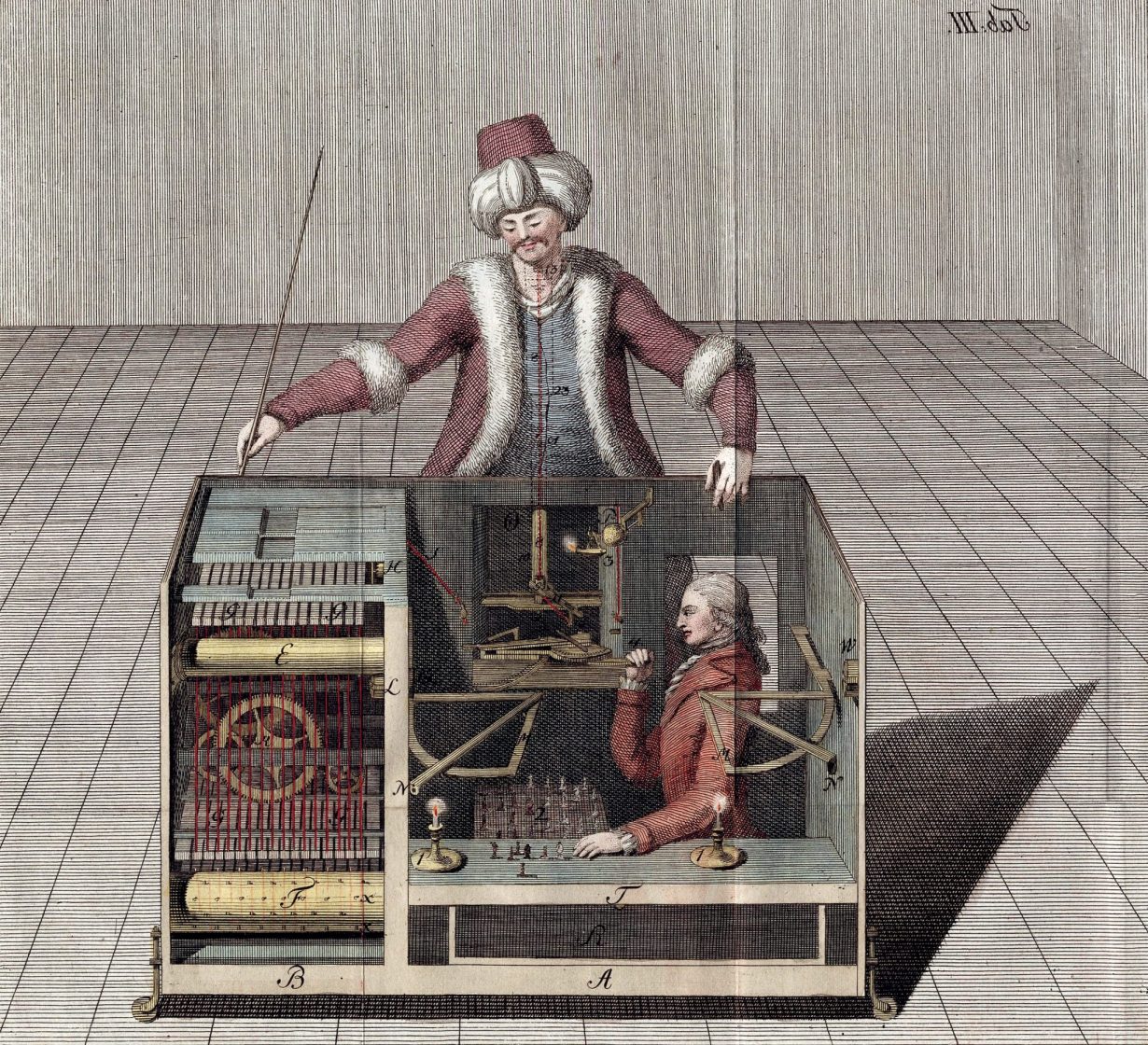

Magic has long led the imagination with its dreams of immortality and super intelligence, while modern science merely works to execute its plans. This is the subject of the first 50 pages of Shelley’s Frankenstein, where Victor’s love of alchemy and occult hermeticism collides into eighteenth century notions of natural philosophy and modern science. ‘These were the men’, Victor’s tutor Doctor Waldman explains, ‘to whose indefatigable zeal modern philosophers were indebted for most of the foundations of their knowledge.’ Even today, science measures itself against the standards set by magic. AI hype, for example, thrives on discourse that mystifies what has often amounted to little more than a Mechanical Turk that spews Magic 8-ball truisms based on predictive analytics.

But every century has its arrogant tech bros and greasy profiteers, and I won’t credit del Toro for adapting a novel as prescient as Shelley’s. But in revisiting Shelley’s novel, I wondered if she wasn’t already criticising the tech bros specifically, instead of technology as a whole. In TechGnosis: Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information (1998), Erik Davis writes that while Frankenstein was a ‘cautionary tale’ for its time, it also turned electricity into ‘an image of the romantic spirit itself’, citing Leo Marx’s writing of the technological sublime, ‘the awesome and frightening grandeur that the Romantic poets,’ (and, I’ll add, del Toro) ‘associated with nature’ and now ‘became attached to new technologies.’

Like Shelley, del Toro casts technology as a source of awe and fear, too often haunted by spectres of unbridled greed and ambition, but equally endowed with the power to inspire beauty and wonder. The director is at his strongest when he uses the magic of filmmaking to show us how technology is a way of getting closer to – and perhaps sometimes too close – to not just the power, but also the beauty of nature, and by extension, God. His Elizabeth, played by Mia Goth, is less concerned with the ‘aerial creations of the poets,’ and more easily moved by the symmetries of the human spine. An amateur entomologist, she encourages Victor to think of science as a means of approaching the “beauty” and “purity” of “God’s creations”. While these moments in Frankenstein are rare, they are the film’s best. AI itself has never been the issue. The problem has always resided in the people who’ve built it into the “insult to life itself” it’s now become.

Michelle Santiago Cortés is a writer and critic based in New York

Read more What do we actually want from literary adaptations?