New work by the artists and musicians explores how artificial intelligence can remain part of a fundamentally humanist project

After returning from a disastrous expedition to Antarctica, the explorer Ernest Shackleton recalled feeling an additional presence as he trekked across the glaciers. He wrote in his 1919 memoir of an imagined extra member of his struggling expedition: ‘Providence guided us’. Few believed him; though T.S. Eliot evoked the phenomenon in a stanza of his poem The Waste Land (1922): ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you? / When I count, there are only you and I together / But when I look ahead up the white road / There is always another one walking beside you.’ The experience of the ‘third man’, an ambiguous ghostly companion, came to mind earlier this year, at the staging of artists and musicians Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s work at the Whitney Biennial: in a series of digital images, a shapeshifting figure appears to stalk a flat landscape. Their face changes from image to image, but recurring features across the series seem to be a helmetlike dome of bright red hair, braided and trailing down the figure’s thick, army-green suit, which is padded as if ready for a polar expedition.

The images are portraits, of sorts, of Herndon, generated by a bespoke text-to-image model – brief excerpts from a seemingly endless quantity produced by Herndon and Dryhurst’s ongoing online project xhairymutantx (2024). Having previously worked across music (with Dryhurst as a collaborator on Herndon’s albums since 2013), digital art and digital advocacy, the two have ventured further into making exhibitions this year, after the Whitney, to create a series of sound-based installations for a solo show, The Call, on view in the Serpentine Galleries, London, this month. xhairymutantx continues to generate more visions of the morphing green suited figure, but the image of the explorer venturing into unknown territory is one the pair have drawn on before: at the heart of Herndon’s 2019 album, Proto, is the pulsing, anthemic song Frontier, sung by an impossible choir of voices that range from rumbling deep baritone to seemingly helium-induced squeaks. The album came out of a process of developing a machine learning neural network to create music, trained primarily on Herndon’s own voice and compositions. Frontier’s promise of a new world to come feels hopeful, but ultimately ambivalent: “This Earth doesn’t care for what we need, what we breathe / A frontier of green or of dust.” In both projects, the third entity being conjured – the otherworldly companion – is a version of Herndon herself. The unexplained experience of the ‘third man’ might have been a mystery and a novelty for Shackleton or Eliot a hundred years ago, but by this point in time we’ve traversed to the other side of the uncanny valley, where our mystery companions, still haloed by wonder and fear, are now artificial intelligence-generated versions of ourselves.

Images of Holly Herndon generated by xhairymutantx, 2024–. Courtesy the artists

Narratives around the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence often veer wildly between the utopian (create anything you can imagine!) and the doom-laden (if not taking our jobs, then taking our lives, Terminator Skynet-style); a sort of binary that seems unavoidable when the most audible voices are generally the megalomaniacs financing these systems and those trying to stop being exploited by said megalomaniacs. While coming to prominence in creating music that was both danceable and cerebral, that used technology to question how the voice and the body might exist in a hyperprocessed present, Herndon and Dryhurst’s work has, for the past decade, been more exploratory and cautiously optimistic about AI, trying to find interesting and more ethical uses of what they have described as humanity’s most recent ‘coordinating system’ – a way to collate and organise sounds, ideas and uses of time. Herndon has, in various interviews, described choirs as one of humanity’s most ancient coordinating systems, and techno’s 4-4 beat as another. We might consider an art exhibition as yet another. Rather than some sort of uneasy ‘other’, they cast AI as more of an unsteady reflection, something Dryhurst describes as “us in aggregate”. “Instead of being like, ‘Isn’t that some crazy alien intelligence’, it’s more like, ‘Isn’t it cool that humans created this thing together, that’s from us,’” Herndon told me recently. “Let’s celebrate that and figure out what that means.”

Visitors to the xhairymutantx website can enter their own prompts, same as any other of the image-generating products the curious have messed with over the past few years; though what emerges – whether a bloodhound, Super Mario, Funkadelic’s George Clinton or Donald Trump in a bikini, as some users have requested, in styles from soft-hued semirealist paintings to monochrome tintype photography – will most often still be donning the same green outfit, and a jellyfish-like dome with a web of the red hair. Herndon and Dryhurst’s model has been trained to create an essential caricature of Herndon, but the aim isn’t just to fill the internet with knee-jerk-funny pictures, or even to ogle at what bizarre or accurate scenes AI can churn out. The project began with seeing what public imagery of Herndon existed (as the more publicly prominent performing figure of the two), and setting out to disrupt that. While the project produces an endless amount of imagery, the work itself is located more in the prompting: users are slowly reshaping the malleable mass of public data, effectively training models that scrape the internet and altering what their future responses to ‘Holly Herndon’ will look like. The mirror-entity wanders further into the wilds.

Behind the portraits are communally trained methods by which we deploy data, and creating and manipulating such protocols has been the duo’s long-term focus. “The most interesting decisions start happening upstream of the production of media,” Dryhurst says. “How you train the model, what the model does, who gets paid, is kind of more interesting than any one output from the model. That’s where all the conceptual work happens. The model itself can just keep making stuff, but the data itself is what constrains the outputs of the model.”

The hidden groundwork behind making and performing music lies in training their own music-generating models; for example, Proto, and their show at the Serpentine, involved training AI models by recording and digitising hundreds of voices gathered from choirs, while with the Holly+ (2021) project, any sound file could be uploaded and converted into something ‘sung’ by Herndon. Recently they’ve been working on a series of tools that allow people to determine if, and when, their work might be used to train AI models, including Have I Been Trained? (2022), which lets you check if images of you or your work are already part of that process, and another that blocks your website from AI scrapers. While useful to some, such tools also seem primarily there to pose an argument for awareness and choice: a conscious participation in these coordinations.

Their recent turn to exhibitions, and presenting their work more overtly as art, seems part of a shift to find a more expansive and incidental meeting point between the time-squeezed spectacle of music gigs and the obscured manoeuvring of technology research; a chance to coordinate audiences encounters with the sounds, and the ideas behind them, differently over time. Their output of uncanny AI singing and gurning doppelgangers might seem to have more in common with the digital alter egos in the work of Lynn Hershman Leeson, or recent projects making use of AI by Marianna Simnett and Martine Syms (with both of whom they’ve collaborated), or the steady stream of artists dabbling in machine learning. But it might be more appropriate to consider their work in light of conceptual art that focuses on instructions and infrastructure – whether Yoko Ono’s text-performance pieces, Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s work with cleaners and sanitation workers or, more recently, Fernando Garcia Dory’s work with bureaucracy and legislation. If we are to work with AI and machine learning, Herndon and Dryhurst’s work argues, then it requires more agency and understanding in how the models are trained in the first place. Listening – and perhaps singing along – is the first step.

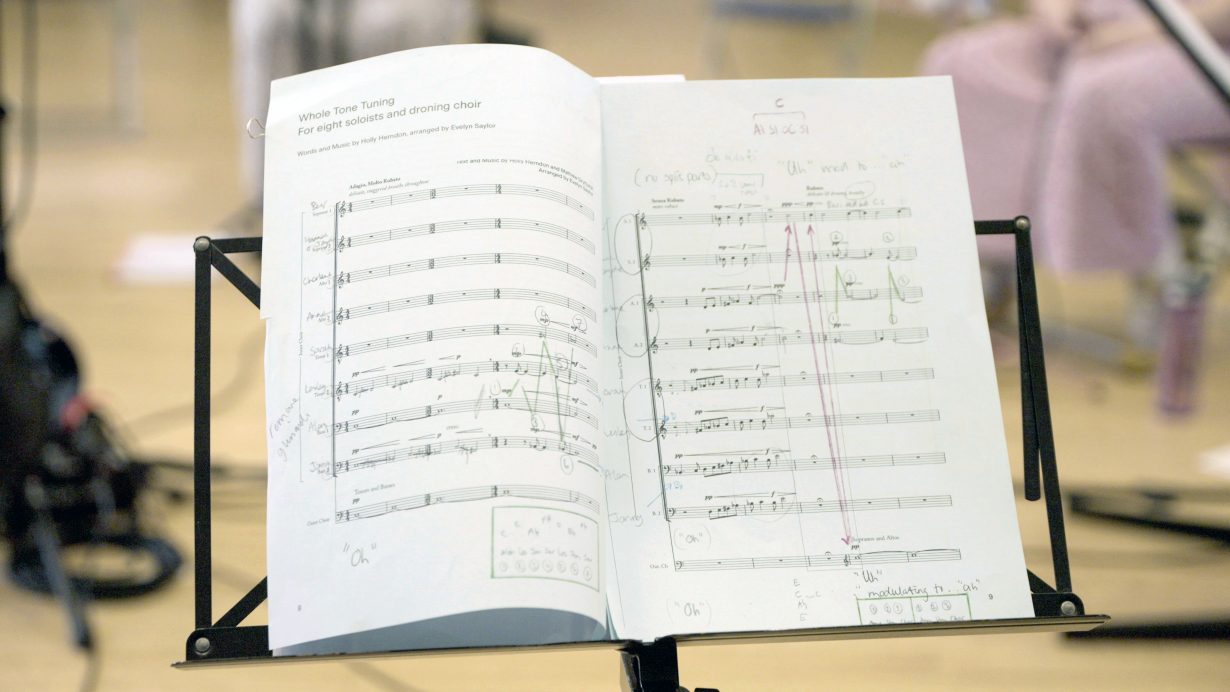

The halls of the former munitions store that make up the Serpentine North gallery (a remnant of another of humanity’s oldest coordinating systems, war) will be mostly empty, filled instead with reverberating choral swells, some more apparently chopped up and modified than others. The Call returns to the pair’s use of music as a primary vehicle, while also attempting to foreground the training that goes into shaping the work. “Some people might think, ‘Oh, you made a model, and then just typed in a few words and have these finalised compositions,’” Herndon says. “That’s part of the material process, but that’s not it. There’s so much editing and composition and all that kind of stuff that goes into it. It’s not, it’s never, plug and play.” The three parts of the show are conceived as an exhibition-size walk-through of the steps involved: the gathering of material, the compression and conversion of that material, and then the unlimited sounds that can be shaped and composed from what the model creates. The Serpentine’s central space will hold The Wheel (2024), a circular metal object reminiscent of an ornate chandelier, from which dangle music-stands bearing the songbook for the 15 community choirs from across the UK recorded for the project; each choir sang a few tunes from their own repertoire, plus the five songs that Herndon and Dryhurst wrote, in order to capture the range of human sounds needed to train a vocal model. In one of the new compositions, O’er Wires, they intone, “Submit yourself to something more.” (Integral to the work as well is a governance body set up to manage the choirs’ collected voice data – while permission has been given to make use of the voices here, their future use is the choirs’ to decide.)

From that raw material we are then exposed to the ways it can be transformed, and what that submission might lead to. A set of panels mounted on the wall provide us with one unlikely version of that: the compression of the choirs’ vocal information into digital files means that it can, hypothetically, be played on any number of instruments – in this case, dozens of small computer-cooling fans are ‘played’ to emit a tangle of cascading notes. The show will culminate in The Oratory (2024), two curtained spaces like prayer rooms, each equipped with active microphones for visitors who wish to sing with, and through, the choir model we’ve seen take shape. Each of these rooms carries an ornate, near-gothic aesthetic, as if sections taken from a cathedral or the more blinged-up version of a videogame rendition of a medieval church, with gold leaf-embossed detailing of patterns and figures seemingly inspired by moments of the recording process. I wonder if the religious implications weigh heavy here, in drawing on an architecture designed to impose on and subsume the individual, and whether this might be a nod to technology as the church in which we genuflect these days. The two artists, though, see it more as drawing on choral architectures, and on religious spaces as “archives or libraries of intergenerational continuity”.

It’s here, perhaps, among a constantly shifting composition of choral music, the voices an amalgam of the human and beyond, that Shackleton’s evocation of providence returns. If we want AI companions and collaborators, there is conscious and deliberate communal work to be done in how they are created and managed; and there is also some element of belief – to be willing to share and step forward with this spectral aggregate entity. The Call models Herndon and Dryhurst’s protocols for exploration, and it’s clear which hymnbook they’re singing from. As another line from O’er Wires puts it: “Minds communing with other kinds, we have to learn to trust.”

Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst’s solo exhibition The Call is on view at Serpentine North, London, 4 October – 2 February