Can our current circumstances offer an escape from the metropolitan networking that has dominated the artworld in recent years?

The memoirs of an art critic should ideally include a chapter in which the adolescent narrator wanders into a small gallery in a rundown neighbourhood. A conversation with the gallerist should segue into a vernissage, at which the aspiring writer should meet a cast of colourful artist types who introduce him to the avant-garde and substance abuse. At a later point they should die, leaving the critic with the duty of writing them into art history and securing his own place in it. Alternatively, it should feature a formative journey with a college roommate to Italy, in which case the chapter should climax in a transcendent experience of art at the Uffizi and a tearful commitment to the lifelong pursuit of beauty.

At the risk of plot-spoiling my own memoirs, my originary experience of art was colouring-in a patchwork elephant on the kitchen table. My Year One classmates misread the homework assignment, whether through literalism or laziness, and filled in their printed templates in monochrome pencil grey; I painstakingly outfitted mine in a harlequin coat of many crayons, and was rewarded with an exhibition on the pinboard at Droitwich Library. My formative experience of a museum came on a school trip several years later to Tate Liverpool, during which the advertisement to my fellow pupils of any transcendent experience of art would have had damaging consequences for my social prospects.

In the absence of revelations likely to interest a major publishing house, I first got into art as a result of its overlaps with the other forms of culture in which I was interested – music videos and poetry, independent films and album covers – and then, fatefully, art magazines. Which is to say that my foundational experiences of art were mediated, solitary, contaminated by other disciplines and took place at home. So our current circumstances do not, in the context of my engagement with visual culture, feel like a privation to be endured so much as a return to source.

Without downplaying the horror of the wider situation, I must confess to enjoying this aspect of confinement. Having never shaken a provincial’s suspicion of the metropolitan artworld’s tendency to dress up networking, sex and social climbing as some kind of mystic intellectual communion, I have always been wary of the saw that art can only properly be experienced in person. This auratic pronouncement often masks the aristocratic conviction, laid bare in the artworld’s society of private views and dinners, that art is reserved for those who live in the cities where it is exhibited, have the resources to own it or were brought up within its codes. This emphasis on personal interaction translates into a community in which individuals’ conspicuous presence – and the ability to identify the right people and endorse their opinions – is valued over the less visible and more independent pursuits of reading, thinking and making.

A reproduction in print or onscreen might not perfectly communicate the experience of a painting, but the notion that this disbars the viewer from responding to it emotionally or intellectually is idiotic. Besides which, some forms of art benefit from their transferral into media that can be enjoyed at home. Take for example the artist film programme currently being exhibited by This Long Century, to which I was alerted by the indispensable ICA Daily email. A refreshingly uncomplicated organising principle – 30 moving-image works divided into two programmes titled ‘Inside’ and ‘Outside’ – presents artists, filmmakers and artist-filmmakers including Ben Rivers, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Jodie Mack. One pleasure of the format is the opportunity to spend time with works previously encountered only in passing, or in contexts unsympathetic to the work. My first experience of Haris Epaminonda’s dreamlike collage of Super-8 footage shot for Chimera (2019) at last year’s Venice Biennale, for example, was undermined by its being screened in a crowded room, off a corridor filled with curators being insincere towards one another. I can now watch its 35 minutes from start to end on my sofa, without interruption by air-kissing.

I can sit through John Smith’s great one-liner OM (1986) with a cup of tea and a biscuit; squeeze in Caroline Monnet’s Mobilize (2014) while dinner is in the oven; connect my laptop to the television and settle into Beatrice Gibson’s A Necessary Music (2008). These conditions are not as perfectly controlled as the artist might wish, nor do they work to the advantage of every piece in the selection: Margaret Salmon’s intimate two-channel film I you me we us (2018), for instance, is diminished by its transference from 16mm onto video, and the absence of a projector’s whir and the cut of its beam through the darkness. But even in this case the damage is not fatal, certainly no worse than seeing a sculpture reproduced in a book and resolving to seek it out at the next opportunity.

How art will survive commercially in whatever new reality lies over the horizon is a different question, of course, and to browse David Zwirner’s commendable Platform London initiative is to be reminded of how dramatically installation shots fail to generate the rarefied atmosphere on which galleries depend when setting their prices. Yet it also alerted me to Sara Cwynar’s Red Film (2018), a short video in which the Canadian artist tells a story about the semiotics of red until she’s blue in the face. The piece works in this context because it adopts, in order to critique it, the visual language of advertising that has for decades been beamed into our living rooms via commercial television.

To watch Cwynar’s work on a small screen at home complements rather than compromises her message. In fact, so much moving image is now edited on laptops, using materials culled from open online sources and appropriating the aesthetics of videogames or video-sharing platforms, that its display on wall-hanging screens in pristine galleries can seem perverse. Darren Bader’s video file (BTD), part of an intriguing if inconsistent ‘group show’ hosted by Washington, DC’s Von Ammon Co., feels designed to be chanced upon during an idle browsing session. Not to mention that its parenthetical acronym – Bored To Death – suggests that the artist might have been responding to the same psychological circumstances in which his work is now being discovered.

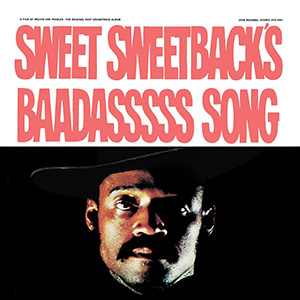

Online viewing has other benefits. Watching Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie (2015) via the BFI Player, I was troubled by the faint memory of having briefly seen, or been told about, a video essay by Moyra Davey weaving reflections on motherhood into an homage to the Belgian filmmaker. So, when the film ended, I typed the question into a search engine, and was directed to a screening of Hemlock Forest (2016) on Vimeo. Now, I thought as I watched this collage of literary fragments and memoir, I am curating my own programme! Davey’s meditations on identity formation then reminded me that Metro Pictures is screening Isaac Julien’s Baltimore (2003), which led me via Melvin Van Peebles to Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971). I’m drifting through the modular architecture of an archive containing more art than any museum could hold, generating my own connections! Art and life are reconciled on my kitchen table! So why didn’t I do this before? Well, partly because galleries weren’t making so much material available online, but largely because I was on the underground coming back from a Chantal Akerman screening at the BFI.

The commissioning editor of this article pointed out in our preliminary conversation that experimental film moved into screenings in contemporary art galleries in search of an economy to support it, and might end up moving out of it again as a consequence of the current crisis. It might be that the pandemic has comparable impacts on the exhibition of art in other media, prompting a shift away from open-plan spaces into the kind of portable and immaterial media that can be enjoyed in the safety of one’s own home. As others have pointed out, galleries and museums might now devote more resources to delivering art to people rather than requiring people to come to them, not abandoning art in three dimensions but reconsidering how it is encountered. Instead of confronting visitors with the bald fact of, let’s say, a Joseph Beuys installation and asking them retrospectively to work out the complex social, historical and political context on which its meaning depends – a strategy often ill-suited to contemporary art, and which provokes much popular resentment towards it – it is tempting to imagine a situation in which museums shift their attention to framing their collections online using a combination of images, video and text. Visitors to less crowded institutions might then plan to spend time with works they are more likely to find rewarding, much as when I first entered the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna I made a beeline for the Bruegels by which I’d been obsessed since whim-purchasing a mouldering volume from my local second-hand bookshop.

I like experiencing art at home via print and online media, at least as a complement to experiencing it directly. It works against the recent tendency towards presence and spectacle, and against the preciousness fostered by the white cube: broadly speaking, art is robust enough to survive not only translation into a portable, reproducible and affordable medium but also the distraction of my flatmate boiling the kettle. It is democratic: I don’t go to the Tate because I like peering through crowds of people to see a Matisse that was intended to decorate a drawing room, I go there because I don’t have a Matisse or a drawing room in which to hang it. It relieves art of at least some of the barriers of class and inherited taste that protect it. Yet while I would maintain that you do not require access to either the in-crowd or a universal museum to engage meaningfully with the products of visual culture, this doesn’t diminish the fact that I miss talking about it with my friends. As soon as some form of normality has been established, I’ll plug my laptop into the projector, buy some beers, get them round. We’ll watch a film together, and call it a transcendent experience of art.