How three Japanese artists look to the past to find our imperialist present

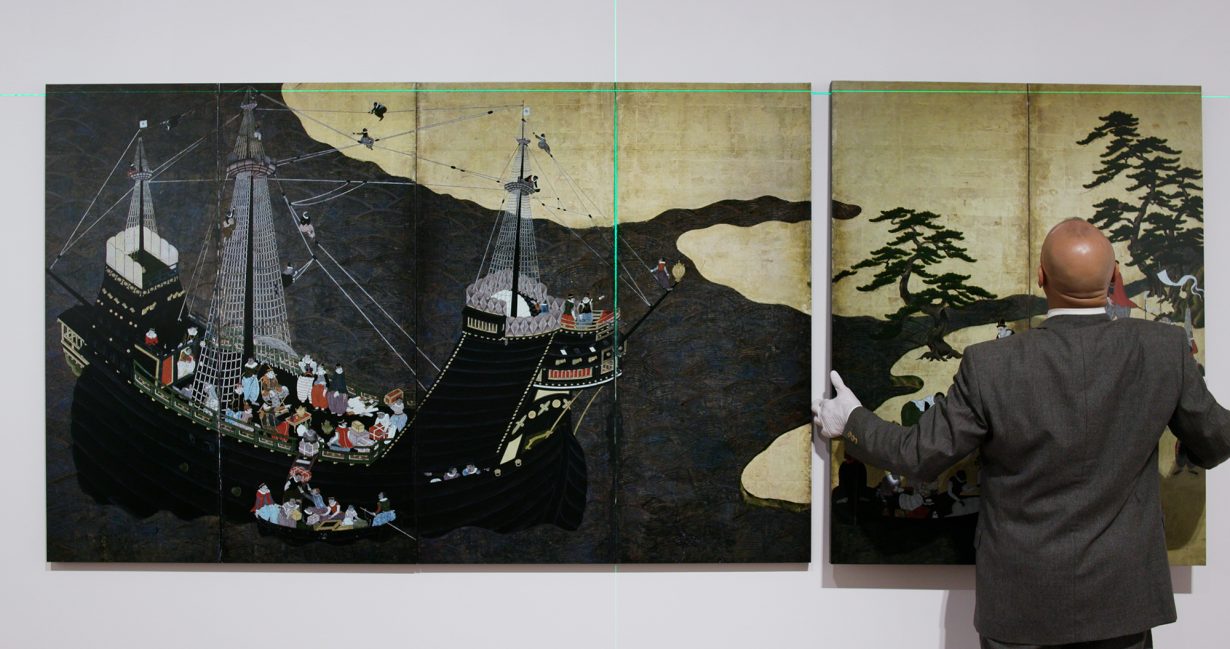

Southern Barbarian Screens, a 2017 video by Japanese artist Hikaru Fujii, opens on performer Peter Golightly adjusting the track lighting in a gallery. He moves one light back and forth across an empty wall as a lighthouse might signal a ship. A few shots later, Golightly wheels a cart into the room, effectively guiding it to port.

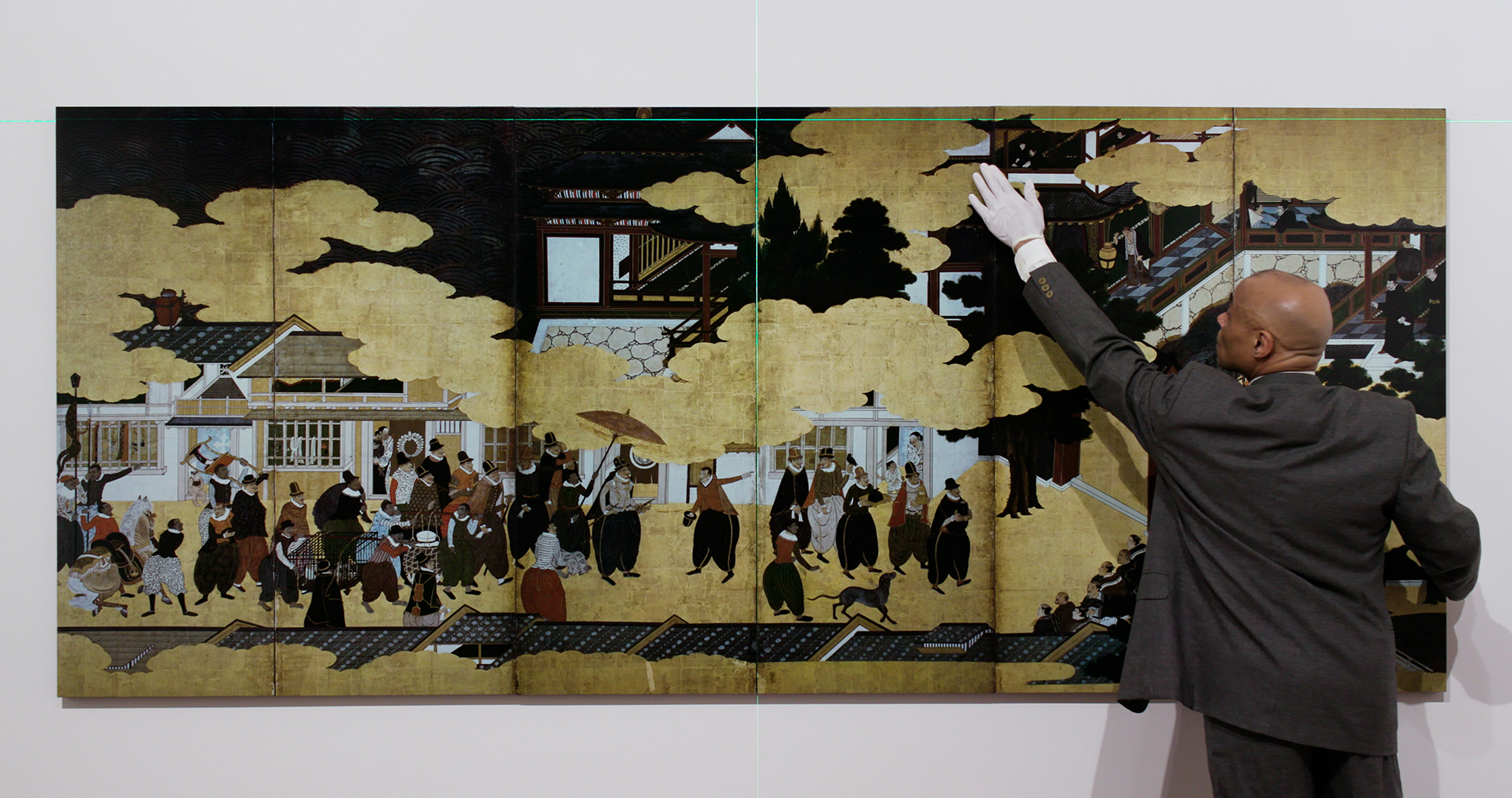

The cart holds photographs by Narahara Ikkō, of a pair of Japanese folding screens reproduced in full-size and enlarged portions. Painted during the late sixteenth century and attributed to Kano Domi, the screens respectively show a Portuguese trading vessel arriving in Nagasaki and the procession of its party through the city. They are among the many Nanban byōbu (‘southern barbarian screens’) made at the time. The word Nanban (‘southern barbarian’) refers to Europeans, the first of whom reached Japan in 1543, landing on the southern coast of the island of Tanegashima. Their arrival altered the religious and political landscape of the entire country, which had been in a state of civil war since 1467, by introducing both Christianity and the arquebus, the latter of which proved decisive in Oda Nobunaga’s campaign to unify Japan.

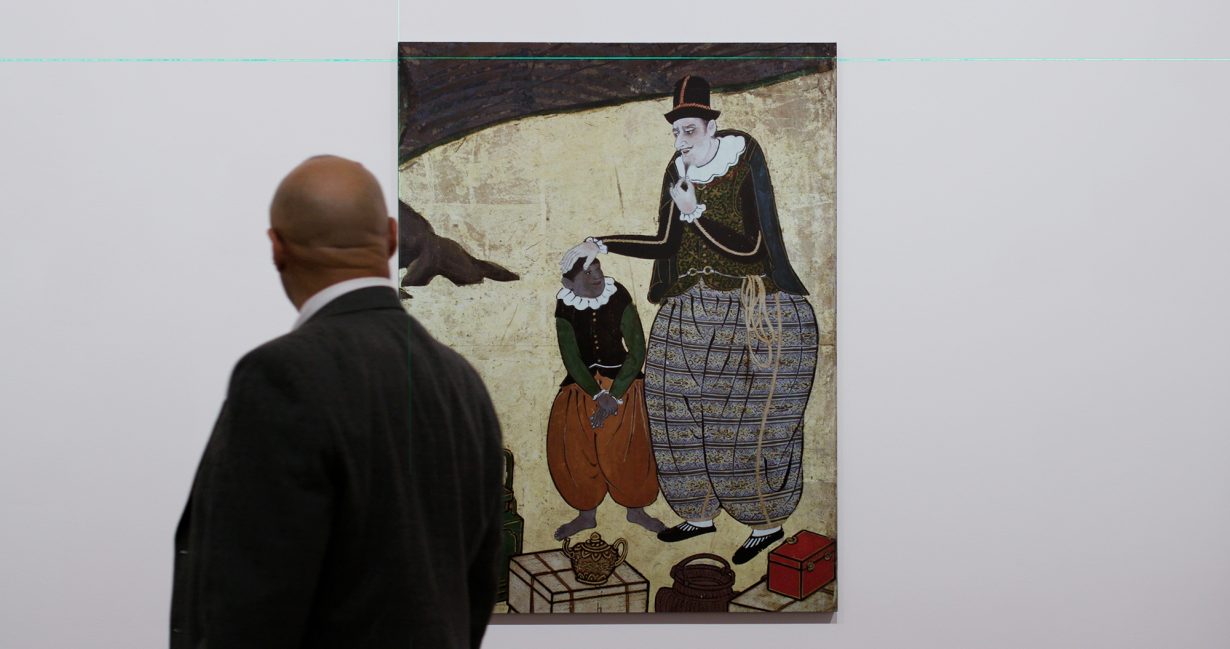

Southern Barbarian Screens is one of several unrelated works of contemporary art by Fujii, Yu Araki and Tatsuma Takeda that consider the politics of identity, slippages of translation and syncretic forms of belief at this historical juncture and beyond, spanning Japan’s period of national isolation beginning in 1633, the arrival of four American war ships in Edo Bay in 1853 that forced the reopening of the country, and the ensuing decades of Westernisation. For Fujii, Nanban byōbu merit scrutiny in being early instances of Japanese artists portraying people of African and South Asian descent, who primarily appear as servants and slaves of the Portuguese. He chose to collaborate with Golightly – a queer, African-American member of the Japanese artist collective Dumb Type – because, he told me, “I wanted to show the gaze of someone who is personally affected by what’s pictured and can take ownership of the issue.”

Wearing linen gloves and his suit from Dumb Type’s seminal performance pH (1990), Golightly appears as a cross between a curator and security guard, whose resistance to the role becomes apparent in Southern Barbarian Screens when he shoves the cart of reproductions and lets it careen across the gallery. At a later moment in the video, after hanging the reproductions, Golightly describes what he sees, including an abundance of gold (a key Japanese export at the time) and what appear to be ‘pleasure ladies’. He speculates about the origins of those in bondage and infers that a younger member of the entourage is being sexually abused by a merchant. The camera stays trained on Golightly’s face for much of his monologue, so we depend on his words to picture some of these details. His testimony shapes our access to the past. In the final shot, Golightly runs towards the camera while staring at us, wordlessly demanding the same degree of critical attention from his audience that he had just given to the screens.

Among the figures Golightly notices in the Nanban byōbu are two Jesuit priests, descending a staircase to greet an arriving party. After the Spanish missionary Francis Xavier reached Japan in 1549, the order gained a foothold in the country, converting an estimated 215,000 residents in the first 40 years and assuming administrative control over Nagasaki from 1580 to 1587. Its success owed, in part, to certain attempts at acculturation: mission churches were often constructed in vernacular styles, and the name of the Christian God was initially translated as the Buddhist deity Dainichi, thus making the faiths deceptively alike. That said, as the civil war drew to a close, the foreign religion became an obstacle to the consolidation of power, leading Imperial Regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi to launch a campaign that persecuted Japanese Christians and sent them into hiding. Proselytising European nations were expelled, and Japan’s period of national isolation began.

In his 2014 video Angelo Lives, Yu Araki finds sympathy with Angelo (a romanisation of Anjirō), a Japanese interpreter of Xavier’s who suggested Dainichi as the translation for God. Anjirō met Xavier in Portuguese Malacca, where he had fled after committing a murder in Japan, and he became the first recorded Japanese convert to Christianity. When I talked with Araki, he wondered: “If Anjirō had been given a chance to make a confession, would God have forgiven him for mistranslating His name”?

Araki made Angelo Lives at a time when he was struggling as an English-language interpreter in the Japanese artworld, growing aware, as Umberto Eco puts it, that translation ‘is the art of failure’. The video cloaks the artist’s experience in the story of Anjirō, who is heard in voiceover chanting the orasho, or prayer, developed by Japanese Christians in hiding (‘Hidden Christians’) – a hybrid of Latin, Japanese and various Romance languages unintelligible to the modern ear. By summoning a ghost from centuries past, Araki tears at the seam lines of history, only to stitch disparate events together, or we might say, mistranslate between them. Inspired by the fact that the first olive cultivar in Japan was named ‘Mission’, the artist wrote a backstory for Angelo Lives in which the cultivar, instead of rooting in 1908 as per the historical record, accompanied missionaries to the country during the sixteenth century. In two scenes from the video, an olive grove, shot by a spy camera lodged in Araki’s mouth, takes on an unnerving animacy, especially when his lips part to make an eyelike aperture, and a hanging olive twitches as a pupil would. The import presents as a witting accomplice in religious conversion, assimilating the body and soul to a foreign diet.

When Christianity was banned in Japan from 1614 to 1873, residents had to register at Buddhist temples and periodically denigrate the Christian faith, often by stepping on bronze likenesses of Christ and the Virgin Mary in a ritual known as fumi-e. Those who continued to worship in secret largely clustered in regions like Nagasaki and Amakusa, where missionary work had been most intensive, and on islands further west. They created small icons that hid their faith in plain sight: for instance, the Buddhist deity Kannon was sculpted to resemble the Virgin Mary. This ‘Maria Kannon’ is often shown holding a small child, and in many cases, a small cross has been subtly worked into its design.

Tatsuma Takeda’s family line is entwined with this history. Records indicate that some of his ancestors reported Christians to the government and were rewarded with titles, while others, living in a small village in Amakusa, worshipped in secret. According to the artist, his maternal grandfather found Mass too “troublesome” to attend, thus ending the practice of Christianity in the family. Even then, Takeda went to a Christian high school in Amakusa founded by a European missionary.

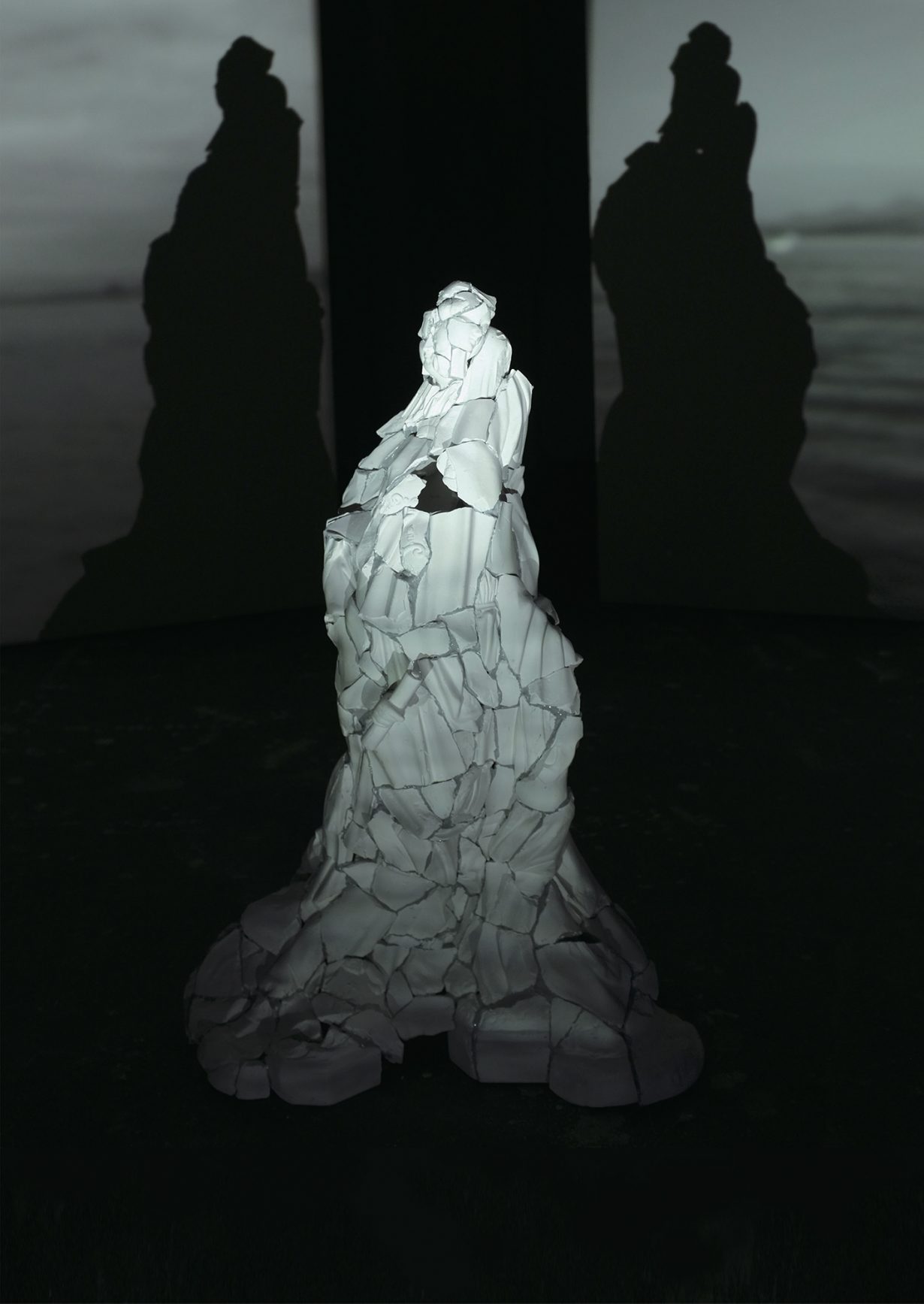

Takeda’s installation memory (2013) centres on an assemblage of gypsum shards shaped like the Maria Kannon, illuminated by a video projection of Amakusa that the artist filmed from the coast of Nagasaki, and another of Nagasaki filmed from the coast of Amakusa, the two shots composed so that their horizon lines appear continuous. In the middle of each shot – roughly halfway between the coasts – is Yushima Island, the site of covert meetings of Japanese Roman Catholics, disgruntled by taxation and persecution, that led to the 1637–38 Shimabara Rebellion. It would be the last largescale manifestation of the Christian faith in Japan for several centuries. In two videos playing on monitors near the installation, Takeda shatters gypsum sculptures of the Kannon and Virgin Mary, revealing the origins of his Maria Kannon’s assembled shards. These acts of iconoclasm, Takeda told me, felt “difficult and dangerous”, even though he’s a nonbeliever, channelling the destruction of Buddhist icons when Christianity first spread in Japan, the violence against Christians during their subsequent persecution and the risk Hidden Christians took in shaping new icons to continue their worship. At the same time, by breaking icons of different religions made with the same material, Takeda suggests that we look beyond the ways that belief is defined by competing dogmas, and instead appreciate it as a fundamental and shared orientation to life.

When American war ships arrived in Edo Bay in 1853, a new struggle over Christianity began in Japan. Within a year, Western Christian missionaries returned to the country to build the Oura Cathedral in Nagasaki and proselytise in the region, which inspired a group of Japanese Hidden Christians to reveal themselves. Campaigns of persecution ensued; during a brutal 1868 crackdown on the Goto Islands, a dozen people took refuge in a seaside cave but were ultimately captured and tortured. The rock formation beside the cave is known as the Harinomendo (‘eye of the needle’) in the Goto dialect, owing to a large central void that, in the eyes of the persecuted, was shaped like the Virgin Mary. To this day, the silhouette possesses an auratic power for believers and nonbelievers alike.

Eight years after memory, Takeda returned to the subject of Hidden Christians with The Eye of the Needle (2021). To make this installation, the artist routed a block of foam, encased in a shipping crate, with the silhouette of the Harinomendo. Projected onto the foam and through the silhouette is footage of the sea taken from the Portuguese coast. Takeda created The Eye of the Needle early in the pandemic, and viewers might think of the particular conditions at the time, when their mobility was constrained, regulated and monitored while goods seemed to travel more freely than ever before. Seen from a broader perspective and with reference to Fujii’s work, the installation is a reminder that the Portuguese ships depicted in Nanban byōbu carried goods as well as icons and missionaries. Religion and trade were imbricated with the project of empire. Language also had an important part to play.

Yu Araki’s NEW HORIZON (2023) tells the story of an American whaler named Ranald MacDonald who ventured to Japan five years before the arrival of the warships, presented himself as a castaway and became the first native English speaker to teach the language in the country. History provides different explanations for his journey. According to a shipmate, MacDonald anticipated that Japan would resume trade with the English-speaking world so went seeking work as an interpreter. In his own published account, MacDonald – the son of a Scottish settler and a Clatsop Chinook leader – speculated that the Japanese were ancestors of Indigenous peoples of North America and hoped to spark a meaningful cultural exchange.

A voiceover of MacDonald’s account runs throughout NEW HORIZON, periodically interrupted by interviews with Assistant Language Teachers (ALTs) of the JET Program currently working in Japan. Since 1987, the programme has facilitated the teaching of foreign languages – mainly English – in primary and secondary schools, placing ALTs throughout the country, including in Yamagata City, where Araki was born. When we spoke, the artist recalled learning English from an ALT as a child and how, even then, he wondered about the experience of a foreigner living in such a remote place. NEW HORIZON poses questions like this to current alts, and if there’s a tacit agenda, Araki notes, it’s to challenge “the presumption that anyone anywhere in Japan should learn English. I think that logic starts to strain in extremely rural settings, which can reveal the colonialist dimensions of the language.” As if to underscore this point, the film takes a CocaColonial turn at the end: as Ranald MacDonald’s voiceover draws to a close, Ronald McDonald (yes, the mascot and clown) is shown walking across a beach to the water’s edge. He gazes in the direction of North America, a pair of rising suns reflected in his eyes.

Araki, Takeda and Fujii turn past Japanese entanglements with the West into subjects of their work. Their field of practice – contemporary art – also emerges from this history. Fujii notes that the “word bijutsu (art) was coined during the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair”, when Japan established an Exposition Bureau responsible for building a collection, part of which would be sent to the fair and the rest kept for the newly founded Tokyo National Museum: the first institution of its kind in the country. In 1877 Japan staged the first of five National Industrial Exhibitions, occurring periodically, but due to the country’s protectionist policies it only admitted the display of foreign goods for the final, 1903 iteration, in Osaka.

On the grounds of the Osaka exhibition, which later became the site for the Tennōji Zoo, was a ‘Human Pavilion’, which purported to exhibit members of the species in their traditional dwellings – including people from Malaysia, Zanzibar, Turkey and Japan’s colonies – while omitting Westerners and the Japanese. The controversy that this created was such that, before the display opened, the Chinese were removed at the request of a Qing envoy. During its run, similar campaigns succeeded in ending the display of Okinawans and Koreans.

Like much else in the National Industrial Exhibition, the Human Pavilion imitated established Western practices – in this case, of displaying ‘savages’ and colonial subjects. Fujii told me that it’s an example of how “scientific racism was used in Japan’s modernisation”. In other words, the display of tacitly ‘inferior’ people, many from the Asian continent, elevated Japan to de facto leader of the region and helped justify its colonial ambitions.

Fujii’s Playing Japanese (2017), which documents a workshop he conducted at a theatre festival, revisits the Human Pavilion from a few angles. In the first half of the video, the classificatory violence of the pavilion is directed at the mostly Japanese workshop participants, who are prompted to arrange members of each gender based on those with the most and least Japanese-looking features. In one particularly uncomfortable moment, a woman questions her place in the lineup: her features are Jōmon, and her ancestors – considered the earliest inhabitants of Japan – occupied the archipelago from 14,000 to 300 BCE. The lineup, however, privileges women with faces associated with the Yayoi, who began immigrating from the Asian continent to Japan around 300 BCE. The group considers her point but keeps the existing order because it’s “more natural”.

The second half of Playing Japanese finds participants reading aloud historical texts related to the Human Pavilion. One person quotes a writer arguing that people from Okinawa, which was annexed by Japan in 1879, are substantially more modern than other groups colonised by the Japanese, like the Ainu and Taiwanese, and thus should not be displayed alongside them. Another participant reads a speech by the Ainu Fushine Yasutaro, who agreed to be displayed in the pavilion in order to raise money for Ainu schools. (The participant is encouraged by a peer to perform with more feeling as he’s telling an “uplifting story”.) These attempts at re-performance do more than elicit sympathy with historical subjects or provide the comforting illusion that we have evolved beyond racist attitudes of the past. In fact, the workshop took place just after Trump instituted his first ban on travel to the us from Muslim-majority nations, and Fujii began by discussing the matter with participants. His viewpoint, he told me, is that “we are Trump, we are the racists”, though many of us have been conditioned to carry our biases so covertly that we can scarcely discern their existence or effects. With Playing Japanese, Fujii attempts to make our “internalised, imperialist gaze” more fully known to us. As Araki’s and Takeda’s works reveal, this gaze can distort through translation and get blindered by dogma, but in all cases, it profoundly colours the way we perceive the world.

Tyler Coburn is an artist and writer based in New York. The research and writing of this text were supported by The Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.

Haruka Ueda provided interpretation for Coburn’s interview with Hikaru Fujii.

From the Winter 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next Who gets to tell the story of Singapore?