A personal ode to the role art can play in going beyond the headlines to reclaim the humanity of those affected by global displacement

On a muddy Kentish beach, a small group of people come ashore at Dungeness. In this barren and remote landscape, a nuclear power station watches over the pebbled garden of the late English artist Derek Jarman. A small newspaper photograph, published this July in the Guardian, captures the scene. The image of these anonymous figures as they are helped onto land by rescuers gives away little about them. Who are they, and why have they come? Why have they had to be rescued from a ‘small boat’ in the English Channel? Most will assume that they must be ‘illegal’ migrants. And then we turn the page.

For the first time in 2022, the number of forcibly displaced people exceeded 100 million, according to figures from the UN. Global migratory movements continue to increase, driven by the escalating climate crisis, war and poverty. The photograph published in the Guardian is yet another example of a visual trope (alongside barbed wire and boats) so often repeated in Western media as to be rendered mundane. Routinely depicted as faceless hordes, vulnerable victims or dangerous intruders, they become the subjects of public debate in which their stories and experiences are treated as currency. What role can art play in showing us their dignity and personhood? Artists can offer an alternative perspective to the seemingly constant alarmism with which migration is framed.

Across the English Channel from Dungeness lies Calais, often synonymous with migration to Britain as the final crossing point from Europe. It was here in 1748 that William Hogarth set his satirical painting O the roast beef of Old England (The Gate of Calais), an indication of just how politically prominent this border has remained over the centuries. The scene shows an enormous side of beef destined for the English Inn at Calais while French and Jacobite Scotsmen (who fled to France following the unsuccessful Scottish rebellion of 1745) look on enviously. Calais, fortified, is the last bulwark against the threat of the outsider. Laden with nationalistic and xenophobic sentiments, Hogarth’s scene juxtaposes the honest meat of Englishness against the perfidious other. Today the outsider landing on British shores might be Afghani, Syrian or Eritrean, arriving in search of safety but no less vilified as invaders. This body of water has long carried migrants, from the Huguenots in the seventeenth century to European Jews in the early twentieth century and Kosovans in the late 1990s. The fortifications were never what they seemed; the borders were always porous.

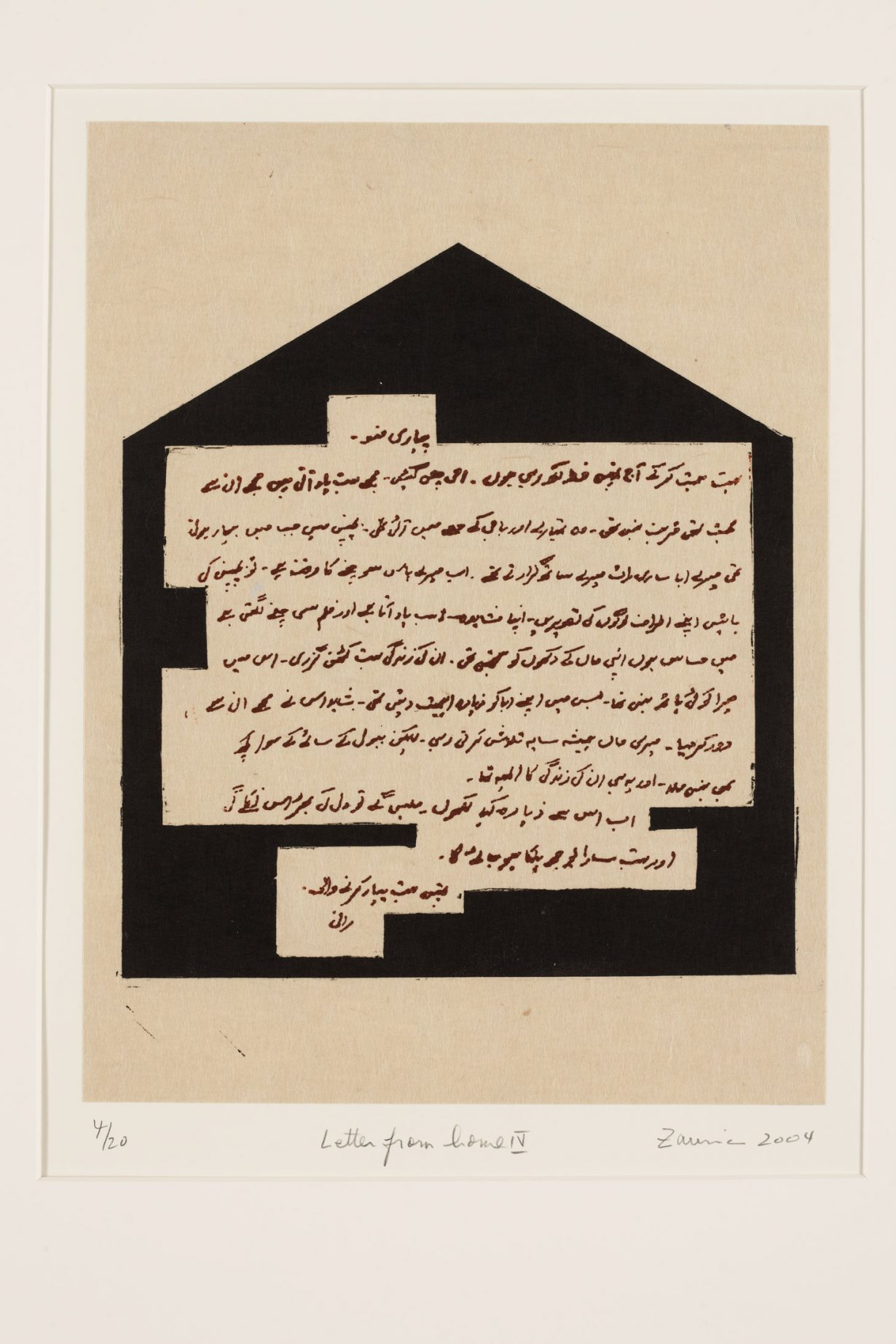

The human reality of these journeys is conjured by a pair of green and yellow suitcases, connected with long strands of hair, in British-Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum’s Exodus II (2002). She maps out an art of displacement that, on an intimate, domestic scale, captures the experience of those forced to flee from conflict, violence or persecution. The strands of hair attest to the remaining fragile connections to home. Even if a migrant reaches safety overseas, that connection to their past remains. The tactility of such connections is explored by the late Zarina Hashmi, a Muslim-born Indian-American artist in Letters from Home (2004), a portfolio of eight monochromatic woodblock- and metal-cut-prints based on letters the artist’s sister had written to her in Urdu. These works map the migrant’s fractured identity, reconciling loss with memories of home – a space between forgetting to remember and remembering to forget.

The challenge for any artist who addresses the brutal reality of far-right politics, capitalistic systems and border violence lies in handling these issues with sensitivity and care. The realities of forced migration often sit awkwardly within the white walls of a gallery, jarring with audiences whose own experiences have little in common with the subjects presented to them. Art since the ‘migrant crisis’ has at times strayed into the voguish, taking on a sometimes exploitative dimension. In 2019 Christoph Büchel presented at the Venice Biennale a controversial display of a shipwrecked boat that sank in 2015 in the Mediterranean sea between Libya and the Italian island of Lampedusa with 1100 migrants aboard. There were just 28 survivors. Titled Barca Nostra (Our Boat), the vessel was presented without any accompanying context or text, stripping its former passengers of their humanity and leading to artworld spectators posing for pictures in front of the work in a crude meeting of two different worlds.

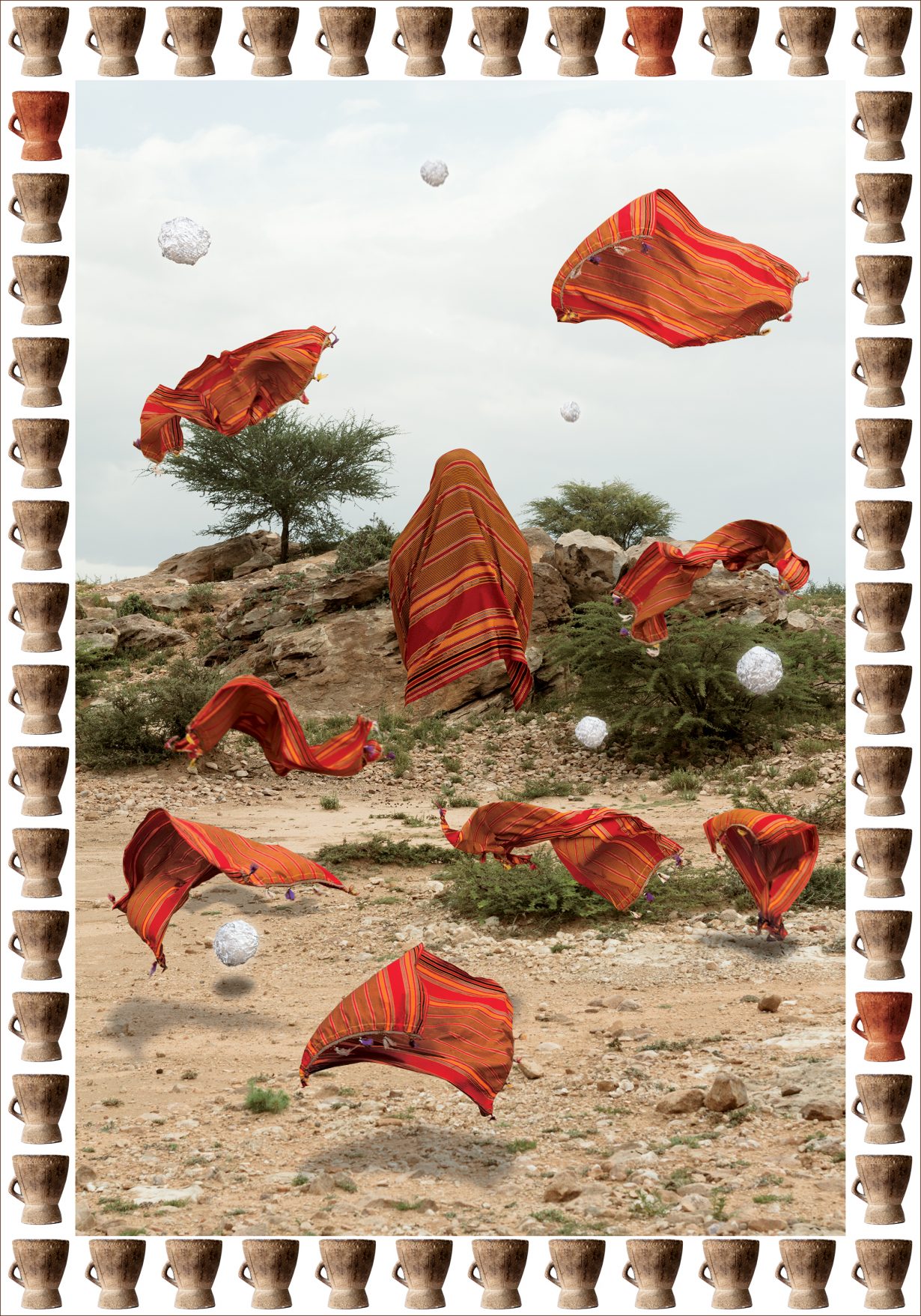

I know intimately the feeling of being forced to leave your home behind; the experience never leaves you. Born in Hargeisa in Somalia, I was three years old when the city spat me out in 1988. As fighter jets streaked across the blackened skies dropping bombs, my mother scrambled to dig a hole outside our home to bury the family photos under a tree she imagined she would return to one day. She never returned, and nothing of that home remains; only loss and fragments of memory endure. When I search for images of the civil war in Somalia, I encounter the malnourished children and decimated cities in the news media, which bring me nowhere near those photographs in that hole in the ground. But the work of Somali photographer Mustafa Saeed takes me closer to my lost memories and my three-year-old self. In Monument (part of his 2014 Home and Me series), shot just outside Hargeisa, Saeed evokes the beauty of the Somali landscape, showing an acai tree in the background in the vast dry savannah lands. His images provoke an almost sensual response in me. Their depictions of the comforting rituals of the Somali home remind me of having liver for breakfast or drinking a warm Somali ‘shah’ (a spiced tea) and lighting an incense burner known as dabqaad or girgiri.

In Somali, the word ‘buufis’ means ‘to blow’ or ‘to inflate’; it relates to the spiritual act of migration in a culture defined for decades by the displacement of its people since the civil war began in 1988. Crossing borders, boarding dinghies and surviving perilous journeys are profound acts of not only survival but of the imagination. While many continue to perish needlessly on their journeys, they are driven by the vision of a different future as they set out in search of refuge. Artmaking is an equally imaginative act and shares with these journeys across borders and open water a deep sense of hope.

Ismail Einashe is an award-winning Nairobi-based journalist covering migration and refugee issues. His latest book, Look Again: Strangers, was published by Tate in July 2023