Now in its tenth year, the sugary sweet mobile game has proven a killer app for an era of rising technological addiction

Snap, crackle and pop. There is a delightfully onomatopoeic quality to mobile and Facebook game Candy Crush Saga, none less than in the finale of each level. Once all objectives have been completed, a so-called ‘sugar crush’ is triggered: a deep voice with a decidedly artificial twang announces its arrival before the game itself plays the remaining moves on the candy-filled board; the screen becomes a cacophony of confetti-like candy, the phone prickles with haptic feedback, all while the score at the top of the screen surges upwards. Rather than unlocking a new level, seeing the game whir like this is the true reward of Candy Crush Saga, each animation and sound effect seemingly perfectly calibrated to elicit pleasure within your brain. It’s as if the game has come to life – algorithm, code, and graphics rendered as a kind of magic, suspending you in a stupor for a beautiful few moments.

Ten years on from its release, the ‘sugar crush’ of Candy Crush Saga is the clearest expression of the trance-like state the game (installed on over three billion devices, no less) aims to lull players into. It is marketed as a means of relaxation: ‘Swipe the stress away’ reads one of the slogans on the game’s opening load screen, ‘Chill and unwind’ reads another. Many players will relate to the calming qualities of the ‘match-three’ game – named so because you must match three or more coloured sweets to score points – but there is little altruism about Candy Crush Saga. Despite a monetisation strategy the video game industry calls ‘free to play’, the game has racked up over $9 billion in revenue through in-game microtransactions, the most common of which is the purchasing of additional lives. The longer you play, the more lives you burn through. A hypnotic quality is essential to extracting maximum value from its players.

Candy Crush Saga arrived on mobile devices in November 2012, five years after the release of the iPhone but just as such shiny machines were hitting the mainstream. The game sat in your pocket next to Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, gamified social media that could likewise be described as ‘free to play’. During a decade of stagnant wages, these companies also scored billions in revenue from the sustained attention of their users, though not from microtransactions like Candy Crush Saga but profitable data that could be sold to third parties.

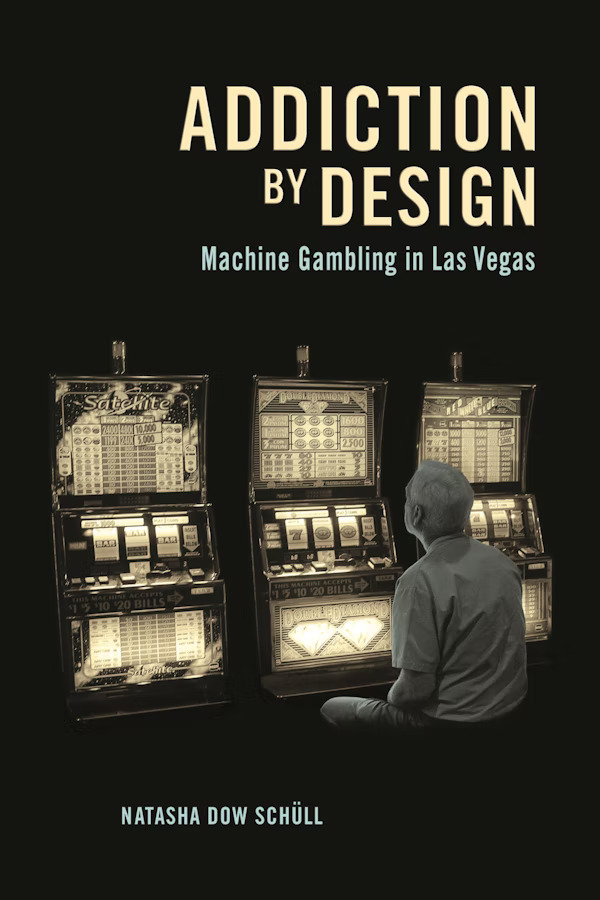

Candy Crush Saga, then, is indicative of a decade in which we all, to greater and lesser degrees, entered the ‘machine zone’, developing technological addictions of various severities that share similarities with those of gamblers. In her 2014 book, Addiction By Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas, Natasha Dow Schüll listens to one addict who describes their interaction with a gambling machine as the ‘machine zone where nothing else matters’. Another says, ‘You can erase it all at the machines – you can even erase yourself.’ Their aim, Schüll suggests, is ‘not to win but simply to continue’. The same is true of Candy Crush Saga: there are over 13,000 levels – the game will never end for most people. Machine gambling isn’t free in any sense but it functions according to the same principle as a mobile megahit – that every moment within the so-called ‘machine zone’ is an opportunity for financial gain. In video games as in gambling, addiction is attention.

The machine zones of video games take many different forms. Often it’s referred to positively in relation to the idea of ‘flow’, a theory devised by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. When experiencing such ‘flow’, it’s commonly thought that reaction times are sharpened and players are able to see a game more clearly, a cognitive state particularly useful for more dynamic interfaces in racing, shooting and fighting games. In recent years, online shooters such as Fortnite have offered wrinkles to such machine zones, providing a space not only for reaction-based competition but virtual socialising. Often referred to as an example of the ‘metaverse’, the ‘free to play’ Fortnite is a space in which you can watch a Travis Scott concert or a Christopher Nolan film, all while dressed in your very own customisable attire using your own set of emotes – everything purchasable via microtransactions. In her 2019 book How To Do Nothing: Resisting The Attention Economy, the writer and artist Jenny Odell rallies against technologies that ‘encourage a capitalist perception of time, place, self, and community’. If Fortnite offers any kind of clues to the future form of the metaverse, it’s that it will likely be a newly intensified version of such capitalism, a ‘free to play’ space even more transactional than those that preceded it.

Candy Crush Saga isn’t nearly as innovative as Fortnite. Its game design was cribbed from 2001 match-three title Bejeweled and ‘free to play’ was already in full swing prior to 2012. What’s perhaps most remarkable about Candy Crush Saga is the ostensible honesty of its central visual motif. Candy is bad for you when consumed in excess; sugar is addictive; Candy Crush Saga is both these things. The author Allen Carr once compared addiction to the carnivorous pitcher plant, luring insects to their death with the fragrant smell of nectar. Once inside, the insect, staring at a pool of delicious, sweet nectar, discovers the walls are slippery, and can do nothing except slide slowly (painfully slowly, one would imagine) to its liquified death.

You can certainly be a Candy Crush Saga junkie, and its pitfalls are real: a bank account obliterated or a social circle deserted. This is never the game’s fault but yours, and in this way Candy Crush Saga, like social media, and indeed the stock market it has been traded on since 2014, reflects the neoliberal values of the time from which it emerged. The risk-reward trade-off is always the same, and so is the burden of responsibility: play the game until it plays you.