On Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona and the medieval turn

Ottessa Moshfegh is a perv. Ottessa Moshfegh is sad girl summer. Ottessa Moshfegh is on Depop. Ottessa Moshfegh is walking in New York Fashion Week. Ottessa Moshfegh is…a medievalist?

For those who know Moshfegh mainly through the cultural commentary that sprung up in the wake of the mind-boggling success of her second novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018), the thought of the author as anything other than an oracle of the contemporary might seem strange. Heralded as the ‘laureate of lockdown’ for her depiction of a socialite in social hibernation – sleeping through a year in a narcotic-induced haze-cum-frenzy – Moshfegh is often thought of spearheading the modern trend for fictions of alienation and disaffection, featuring a cast of recognisably contemporary outsiders. Alcoholic divorcees, catatonic party girls. So, despite the fact Rest and Relaxation was in fact a work of historical fiction (an eccentric yet meticulous account of New York’s pre-9/11 culture; its downtown art scene and existential ennui), and that her debut, McGlue (2014), takes place on a nineteenth-century pirate ship, when it was announced her new novel, Lapvona, was set in a medieval fiefdom, there was an undeniable frisson of surprise.

Although, really, we should have seen this coming. Firstly, because Moshfegh’s novels are abject and pervy; deviant and corporally charged. While it might be convenient to think of these qualities as unique to literature of the post-internet, and certainly the post-Reformation age, in truth they are closely aligned to many of the affective and aesthetic traditions of the Middle Ages. Indeed, the second reason why we should have expected Moshfegh to go medieval, is precisely because the contemporary popularity of grotesque, absurdist fables like hers points to a wider resurgence of medieval tropes and trends. Lapvona is landing at a time when, from the club to the catwalk, neo-medieval fashion, Catholic aesthetics, mysticism, chamber chorals, and pagan ritual are all the rage.

‘It feels like music is returning to some kind of medieval folk medium where we are bards again, self-promoting in the streets or taking the occasional commission from patrons,’ pop-cyborg Caroline Polachek said last summer. Perhaps this feeling is partly why she has, in the past, chosen chainmail, plate armour, and fantastical, elven costuming to accompany her vocals – which themselves have been described as ‘diaphanous and otherworldly, somewhere between the call of a siren and the religious arias of an eleventh-century abbess.’ And she’s far from the only one at it. The worlds of music, fashion and visual art have been flirting with folklore and pagan iconography for some time now. Arrows raining down on models at Paris Fashion Week. Ravers dressed as medieval forest dwellers, dancing to fantasy-inspired techno. Artists merging emergent technologies such as AI and machine learning with myth and mysticism to imagine alternative worlds, which seem to hover and glitch between the ancient and the futuristic. Cinema’s folk horror boom.

While all this has been seething, it might seem like literary fiction has been lagging somewhat behind – its gaze resolutely set on grappling with text-speak, or, in cultural criticism, circling the unending debate over which books men and women should read. Yet, here too, a particular strain of neo-medievalism has been rising to the surface, often in the form of an ongoing obsession with female mystics. Hildegard von Bingen, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe keep recurring in contemporary texts, usually symbolic of an urge towards alternative female authority, power and sources of knowledge. A similar urge can be seen in the copious literary reanimations of Simone Weil, who, despite living in the twentieth century, had a curiously medieval approach to faith and spirituality – one in rapture to sacrifice and suffering. Taken together, the interest in these figures suggests a growing infatuation with medieval forms of devotion, characterised by corporeal and psychic intensity.

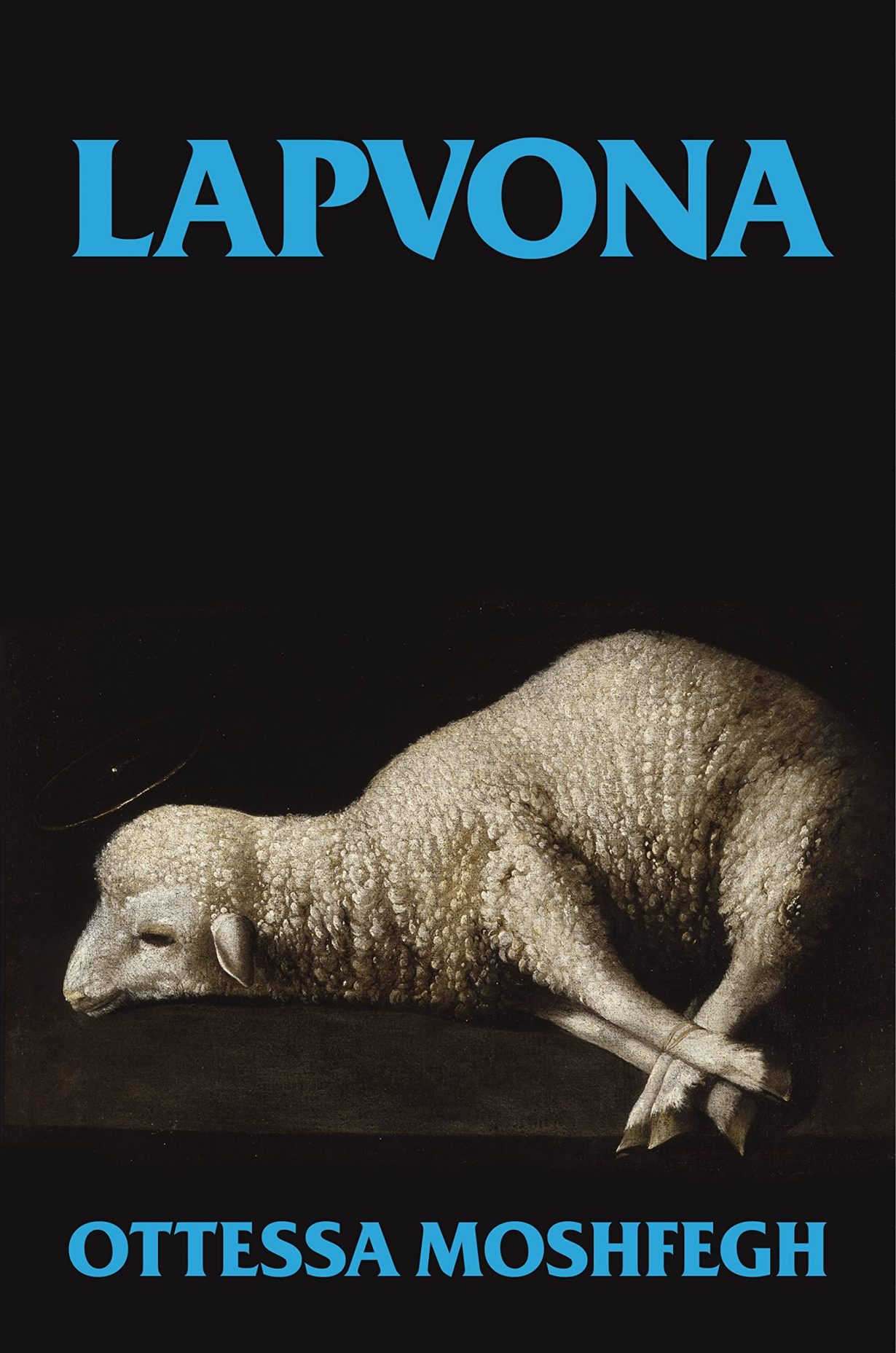

So, Lapvona. During the pandemic, as Moshfegh was being hailed as the queen of modern malaise, she was penning a novel truly befitting an era of pestilence and plagues. On the surface, it seems purposely designed to drive her Tiktok stans into a frenzy. Where, in Rest and Relaxation, there was a beautiful blonde girl who was slim but sad in a vague, yet vaguely sexy way, in Lapvona there is Marek, a 13-year-old disabled boy, who is born of incest, beaten by his father, possibly a murderer, and, if that wasn’t enough, deeply annoying. Where there were New York bodegas, now there is an unspecified hamlet in a quasi-Eastern European locale; a hut in a sheep’s pasture; a manor on a hill, protected by guards. The capricious whims of a feudal lord and the obsequious enablings of a servile priest. A blind female mystic who breastfed a whole town and still allows Marek to nurse from her now empty teats. It is utterly disgusting. While Moshfegh has always been an excremental writer – a devotee of shit – here, the novel also features humiliation, flagellation, murder, incest, rape, a drought, dismemberment and cannibalism. Sacrifice and suffering. There is also though, a lot of shit and anal gags. ‘Excrement,’ the lord Villiam wonders. ‘Is that like sacrament?’ In Moshfegh’s hands, it absolutely is. Lapvona is a sublime work in the truest sense – mighty, irrepressible and terrifying.

Some early reviewers have already taken against it. One notably likened the setting and characters to Shrek (2001). Yet, while this may be a wry, internet-y scrap of criticism, those calling it flat, or tedious, or excessive are, to my mind, entirely missing the point. Saying Lapvona is either flat or excessive is like saying the same of Robert Eggers’ The Northman (2022). Lapvona should not be read as a modern narrative, but akin to a fable, allegory or epic. More than anything, perhaps, it is a kind of medieval sci-fi, and, given sci-fi’s long history, perhaps what I really mean is a kind of myth.

Yet, this is certainly not to say that it is untethered to the present, or that the medieval turn we are witnessing is a turning away from the specificities of modernity. And, by modernity, I of course mean capitalism. Just as Polachek’s notion about returning to a bardic culture is, in fact, a biting critique of the contemporary music industry, streaming services, and the flexibility and self-reliance required of artists in the neoliberal age, so too Moshfegh’s medieval fantasy is not just about shit and blood and supposedly timeless human impulses to violence. If Lapvona is a myth, it is one of exploitation, wealth hoarding, and ecological disaster at the hands of uncaring, greedy men. Indeed, the entire cultural flirtation with medieval aesthetics can be read as an attempt to grapple with the perverse conditions of today – a neo-feudal billionaire class (or, as economist Yanis Varoufakis puts it, ‘techno-feudalism’); a lack of access to land ownership; a new era of pandemics; food poverty; the existential threat of climate apocalypse. Time for a peasants’ revolt?

Of course, the risk with any cultural or aesthetic turn to the past, is that it tips into idealisations – false fetishisations that construct convenient and, often, dangerous narratives. If thinking of The Northman, for example, it would be ignorant not to also think of the way Viking mythology and attire has been adopted in the modern day by the alt-right. The myth of white racial purity; the horned helmets in the Capitol. Music, fashion, and art’s shift towards the neo-medieval may not have such an explicitly racist underpinning, but we should be wary of which histories are being reclaimed as trends.

Perhaps one answer to this problem lies in resisting romanticisation – in depicting the past, whether real or imagined, as a site of brutality and struggle. The historical fictions crafted by writers such as Moshfegh, AK Blakemore and Olga Tokarczuk, for example, are brutal affairs concerned with power, control, and the origins of capitalism. They wield history like a blade, cutting through the fabric of contemporary reality. Blakemore’s exquisite novel, The Manningtree Witches (2021) is about the witch trials of the seventeenth century, but it is also about persecution, suspicion, and how easily fear, pride and conspiracy can tip into violence. This is true of Lapvona too, which is, in a deep and essential way, about faith – about truth, knowledge, scepticism, and how easily people can fall sway to the empty words of demagogues. ‘I feel stupid when I pray,’ reads the epilogue – a Demi Lovato lyric that proves that, while everything from that point onward may be new territory, Moshfegh still has her eye firmly trained on the details of the current moment; on contemporary blindnesses, barbarity and fears.