‘‘We are convinced that access to spirit-worlds can help us to move beyond linear and hierarchical genealogies of knowledge that has been shaped by and through extractive forces and colonial modernity.’’

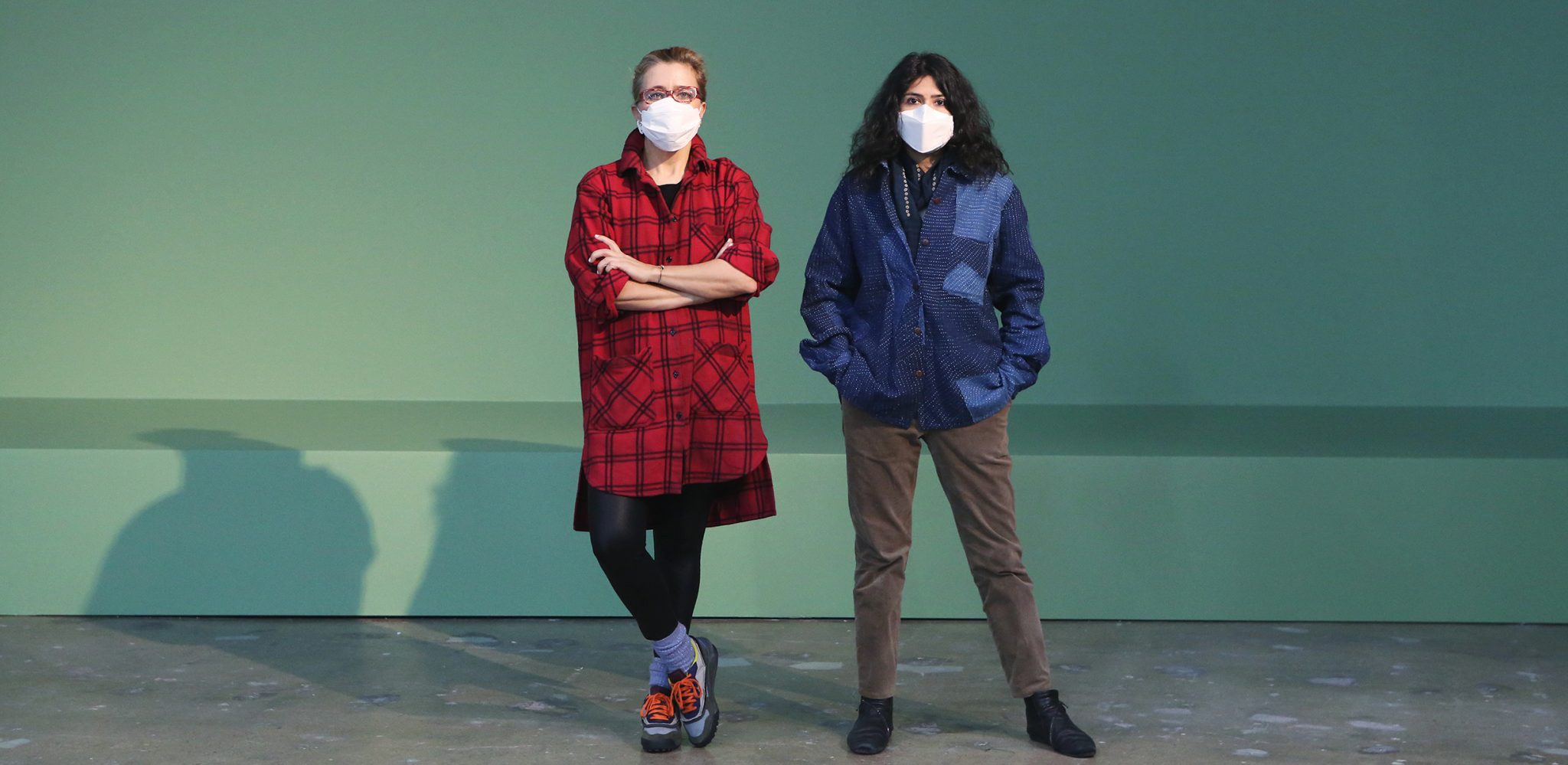

After two postponements, the 13th Gwangju Biennale, titled Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning is set to open this April. ArtReview Asia caught up with its artistic directors, Natasha Ginwala and Defne Ayas to talk about the challenges of curating during a pandemic and the resultant lockdowns, and about their hopes for the show when it opens.

ArtReview Asia Your edition of the biennale was originally scheduled to take place last year, but has since been postponed eight months to open this April. That naturally involves some reconfiguring on a practical level but did the situation with COVID-19 also entail some conceptual reconfiguring?

Natasha Ginwala During the time of the postponement we did have conversations on whether to dramatically restructure, restage or recompose. Artists were already in the midst of production by then. In the end we did not. Our plans are pretty intact. It’s a huge shame that we’re not going to be able to share most of this with the community that we built, paving a path stone by stone, all these years. That is tragic.

ARA I guess you have to anticipate that, in some ways, the way people read the world and the objects in it has changed over the past 12 months.

NG Absolutely and that’s what we’re interested in. We remain attentive to exploring what the filter of readings will do to the premise. Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning inquires into the communal mind, augmented tentacles of surveillance and bodies in dissent, which is speaking to the times with more vigour. That’s almost scary at times.

Defne Ayas We set out to examine the entire spectrum of intelligence, with both the organic and inorganic intelligence in mind. Some of the questions we asked were: What is the true nature of intelligence? How do we learn survival strategies from living organisms and microbial agents? What is foreign in us that also benefits us? Where are we heading in our coevolution with artificial intelligence? These initial questions in our proposal have become more relevant, they have been pandemic-proof I would say. The curatorial inquiry kicked off in the form of our online journal, public programmes, and site visits together with our invited artists.

On the other hand, when we got the news of the outbreak, certain commissions had to be temporarily suspended, shipping prices suddenly surged. At that moment, Natasha and I had a discussion about what we were going to save from the fire. That was a more practical discussion, also around that invisible hand of deep bureaucracy, but it also says something about the essence of things. A local turn was inevitable.

ARA What were some of the inspirations for that intellectual pursuit?

DA We were inspired by Catherine Malabou’s work, which talks a lot about the labour of the brain and mutual-aid futures. We just did an interview with her [published in issue 4 of the bimonthly Minds Rising online journal established as part of the biennial] in which she talks about how we can interpret cerebral structures operating within global capitalism, particularly with disembodied or remote working. She says that the task today is to re-elaborate the right mode of dialogue between the organic and the cybernetic brain, which is very difficult, but it is what we have to do. And of course Yuk Hui has been a reference, especially in the pursuit of more heterodox, non-Western ancestries for our understanding of cybernetic intelligence.

NG Other inspiring forces include Ruha Benjamin through her immense work on race and technology; feminist philosopher and essayist Djamila Ribeiro’s contributions to Afro-Brazilian feminism and social justice; and PARI (People’s Archive of Rural India) is another immense resource we are connected with to name a few. The research travels with artists and team in October 2019 and January last year were incredible for in-depth learning and dialogues with historians, shamans, archivists, theatre makers and artists in Korea. The curatorial team has not been able to be together as a whole since then. We haven’t met the Gwangju Biennale Foundation team in person since January 2020 but are now on our way to complete installation on the ground.

DA When the world comes to a stop, how can we be expected to be in motion, in high gear? We haven’t had time to reflect on what the pandemic has done to us all or the biennale as yet because we’re always in this executive forward-motion mode – but in a few months, maybe we’re going to look back and say, “This was really relevant, we’re really happy we did it”, or “Maybe we shouldn’t have made that call”. But now, we really take it day by day, in the eye of the storm.

NG I observed how artists’ productions had started to shift even by degrees at times during the changing situation of the pandemic and the politics around it: there’s a material response that is still arriving into the world and we need to correspond with that mode of arrival.

Take, for instance, Cian Dayrit’s sculptures and ensemble of military paraphernalia that are part of a bigger installation: in these he has already reflected the experience of the militarisation of the pandemic in the Philippines and the Anti-Terrorism Law. I find that extremely important to add to this discussion. Ana Prvački’s work is entirely a response to the pandemic and the performative codes of greeting, the performative codes of masking, the beautification of the mask, the question of wellness being politicised in various ways across Asia now with pandemic included in the recipe.

To answer your earlier question, there are definitely shifts, but the point is also what commitments you continue with. I don’t see this as a kind of naive positivism on our part, I think that’s a degree of granular commitment and an atmospheric exchange of energies, as ounces of cultural labour take a whole lot out of you in the current circumstances.

DA Lynn Hershman Leeson is developing her commission with plastic-eating bacteria and enzymes in collaboration with the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, which got interrupted because the campus got shut down. Gala Porras-Kim, who was a fellow also at Harvard, had to move her studio back to the West Coast. Femke Herregraven, Sissel Tolaas and Korakrit Arunanondchai were planning to travel to Jeju a second time – that was all interrupted. An artist has become a mother during the pandemic. Not to mention the more general parental home-dynamics at play for some of us. So we have had to find ways of working remotely. But that had to be non-extractive because that’s exactly what we’re standing against. There is fine-tuning on every artist element. Reality becomes part of the sculpting of the new commissions: we have 41 new commissions and 69 artists: that’s a pretty big number and shows how invested we are to new readings of contemporaneity.

ARA To many that would sound like a nightmare.

DA But we also feel very engaged with the moment.

ARA One of the things you seem to be describing is that a lot of things have become more locally specific and immediate during this period. It must be quite strange working on a project that’s international in scope and ambition at the same time as everything has, not quite fragmented, but become more isolated. You talked about the Philippines and there are some very specific problems there that perhaps translate to other contexts, but not completely. Are you having to deal with this localisation of experience more? I guess this is particularly interesting given that the Gwangju Biennale was founded as a result of some particular local conditions.

DA On the several trips we made, we hosted artist presentations, including a smell memory workshop with kids by Sissel Tolaas and a feminist game-character building workshop by Ana María Millán. Connecting the dots, which is what Gwangju Biennale does every two years, especially when it comes to capturing the impetus of social movements. The ‘living memorial’ legacy of the Gwangju Biennale is something that we’re certainly unravelling. We also met with civic advocacy groups and now, with our on-site and online public programmes, we make sure there’s always a civic component that comes from Gwangju or across Korea. Within Minds Rising, our journal online (which is going to become part of our catalogue), we’ve been capturing the digital feminism movement, whether it’s through poetry or scholarly texts, that’s been lively in South Korea. The gender disparity is humongous here.

In terms of the local turn, yes inevitable, audiences to the opening will be definitely local. In terms of connecting the local to international and making Gwangju relevant globally, I think we’ve been doing a decent job with how we mobilised our initiatives online, but of course, being remote we cannot sense as much as we wish. We have our eyes and ears there with our curator Joowon Park, editor Young-jun Tak, and of course the coordinators of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation team.

ARA In a sense you’re dealing with a number of artists who are now all over the world – perhaps, where they wanted to be, perhaps where they didn’t want to be – and they are having to deal with various different local situations in a way that might not have been strongly felt previous to this. Perhaps things become relevant to them that weren’t before the pandemic and vice versa.

NG I’m realising that the meta experience of the Gwangju Biennale is almost like a score played in unison – in the sense that every Gwangju Biennale has added a section to the multi-episode composition. There are many parts and there’s been so many different elements that have been constantly supplementing each other or at times even playing an agonistic role, in different editions. It feels like we’re in communication with what has been manifested and adding to this lineage in ways that haven’t entirely been done before. Especially through the tremendous pursuits of artists reckoning with ecological justice, indigenous sovereignty, and gender-defying life models. However, since this edition won’t be seen in its physical dimension especially by many international visitors who know its past, there’s a lot more at stake in that form of virtuality as a meshwork of positions, it differs from the virtual encoding of a dialogue [of this Zoom call]. The virtual is also a memory imprint in terms of what a platform has been. I’m only thinking about it now, but I feel like we need to acknowledge that rather deeply – the decoding and encoding of biennales in disembodied times.

DA In terms of the spectacle aspect of the Gwangju Biennale, which belongs I feel to a previous generation, we’re making a shift. We know that the government and the city expect consensus through the agency of a spectacle: that’s why they fund the biennale. But then, we are also tasked to engage with the traumatic lineage of the Gwangju Uprising [1980] through the lens of contemporary art, which is in its essence non-consensual. And capture all that bottom-up protest energy, upheaval, grief and affect into the exhibition.

My instinct is that what’s going to manifest is also what matters now – essential questions like the ethics of being in the world – what does it look like through the artists we’ve engaged as they are sculpting their work at the very moment, as we are speaking? What is this ecologically, socially desirable state of being in the world? How do artists contend, with their vocabularies, with the current regimes of ongoing colonialisms and algorithmic violence in their respective contexts? It’s what matters that’s really going to be visible. That’s what’s coming. In a way, we’re not really engaging with the question of whether it will or will not be a spectacle at all. In my opinion, it has to not deliver this perfectly packaged expectation. We’re over that modernist biennial aesthetics. We don’t believe in it.

ARA You mentioned the history of the biennale. It feels to me that in Korea, and indeed in many other places right now, both its art history and its actual history are in a process of constant rewriting. There’s something about that that’s great and engaging and interesting because it can give you a sense of agency, but also slightly depressing because the sense of moving on sometimes gets left out, you get stuck with retreading or retreading the past. Particularly in Gwangju.

DA Every two years, whoever is leading this conversation as artistic director also brings a certain criticality to this living-memorial industry, and there is an industry around it, for sure. There are hierarchies of suffering in relation to male and female presences or the lack of queer presences that we felt needed unpacking. We’re also looking at it through the prisms of today because, for example, you can easily connect this mother uprising to the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul or to Hong Kong, Lebanon and Tibet – and this morning, Natasha immediately connected it to the farmers’ protests and student mobilisation that continue to resound in India in recent months.

ARA Yes, but I think that when these issues become a part of art exhibitions there’s a tendency to boil down these social and political movements to a series of objects. Take The Square at the MMCA a couple of years ago: the detritus of protest – shoes and banners – suddenly become the same as art objects. That puts art itself in a difficult position, I think.

NG It is a difficult position and I think in this case we also need to acknowledge the fact that perhaps there will be a reluctant reception toward our model, because it is not about the amplification of the history of trauma through mute objects. It’s actually a processual mode, linked to emergent modes of intelligence- and resistance-building, and the circulation of ideas that germinate across terrains rather than a unilateral story of oppressor and victim. And there’s a constant negotiation of historicity but at the same time, we have to take into account the polarising realities of today. We’re attempting to remain porous to what the tensions and stresses are in Korea. One of them of course, is this question of sexual violence that has come up in a big way politically in Korea; another is Korea negotiating its relationships with various parts of Asia, whether that is Japan or Mongolia.

ARA You’re also attending to indigenous knowledge.

NG Yes, for us, bringing indigenous knowledge and strategies of dissent to the core of the exhibition is extremely important while also acknowledging that we are outside that and we’re learning from these counter-currents as models of ownership, reparation and evolutionary time. The Sydney Biennale curated by Brook Andrew is an excellent example of how biennales can surpass Western colonial narratives to set up convergences around multiplicities and ancient ties. But here again the terms of engagement are not easy to negotiate. We were surprised when a respected Korean artist responded, “How is it (indigenous art making) contemporary? Isn’t that framing an ethnographic approach?”

DA I am perfectly aware that agendas around indigeneity but also shamanism can be seen as orientialist or be hijacked by rightwing agendas or libertarian forces. Yet, they are incredibly powerful interfaces to read through not only historical but ongoing imperialisms. To me, a deeper inquiry into shamanism is highly revealing of various histories of organic intelligences or knowledges that have been suppressed or ostracised. It also works as an interface to understand gender issues and class divides in South Korea. We are convinced that access to spirit-worlds can help us to move beyond linear and hierarchical genealogies of knowledge that has been shaped by and through extractive forces and colonial modernity. We see our involvement rather as part of our mission to connect the many visions and practices across the world, as we try move towards a world model that relies upon more hybrid alliances, that can help us unleash practices of renewal in the face of collective and individual traumas today.

ARA Which I guess brings us neatly onto solidarity and the role that plays as a cohering factor, maybe, within the biennial. Is that about simply paralleling experiences and seeing where they overlap, or is that something you feel you’re actively engendering with this exhibition?

NG There is this very specific aspect of the forums that we are holding that brings together positions and protagonists who would otherwise not meet, either at a human rights conference or at one of the art events that we have been a part of in our more than a decade of practice. It is about joining affinities in a way that requires you to think quite asymmetrically.

Two examples: you have Beaska Niillas from Sápmi, who is talking about divestments from copper mines, moratorium action along the river outside where he lives in Sápmi and you have Marian Pastor Roces and Cian Dayrittalking about the situation in Philippines – peasant struggles, the anti-terror law, the disappearance of young activists, oral history and material culture of religious minorities, etc. They meet each other at a crossroads that is this forum. Then you have Reem Abbas, who’s a Sudanese journalist who talks about looking at the 2018–19 Sudanese revolution from a feminist perspective, in terms of how the visuality and the collective organisation is driven by a feminist logic and representation. Alongside her is Huiyeon Choi, a member of Gwangju Women Link, who also addresses the Gwangju uprising through the feminist lens and challenges the feature of martyrdom being assigned to the male body. We are not going for this kind of celebratory aspect of solidarity. We know we have the vocabulary; but this is an emergent lexicon where the strength lies in accidental meetings and shared volatility.

artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul. Photo: Matthew

Herrmann.

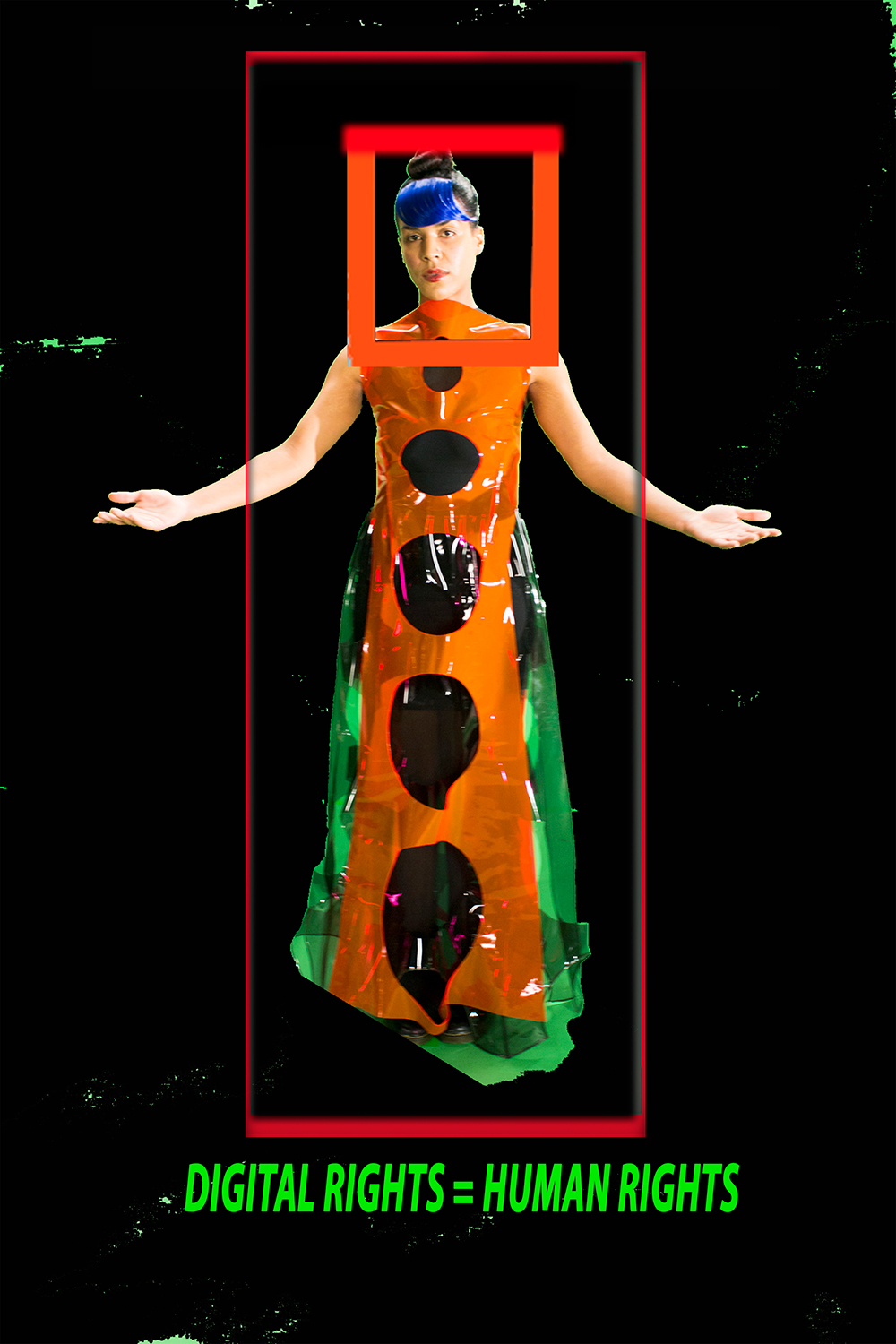

DA The reason we did this forum is to find out what are the tactical strategies that we can learn in the twenty-first century – at a time when governmental surveillance has become so present. How can we re-invent our bodies and re-program them? The choreographer duo ∞OS is invested in this topic for instance. How do we create new layers of consciousness as we are trying to co-evolve with algorithmic surveillance regimes? We have also witnessed moments unpacking collective and individual trauma during the sessions with a Māori healing practitioner, Haaweatea Holly Bryson.

ARA But I’m still curious about how solidarity ends up in the context of an art exhibition. If you take historical models like the Tricontinental in Cuba, it exists more as an aesthetic today than anything concrete. I think there’s a history where the shape of these things carries on, but the actual substance of it gets lost.

NG We’re not necessarily claiming the ground of solidarity as a mission. The forum Rising to the Surface: Practicing Solidarity Futures activates this intention. We are just giving respect, paying homage and colistening to these people who we think are seminal to the ferment and structural realignments of our collective moment and this was something that we started before the pandemic.

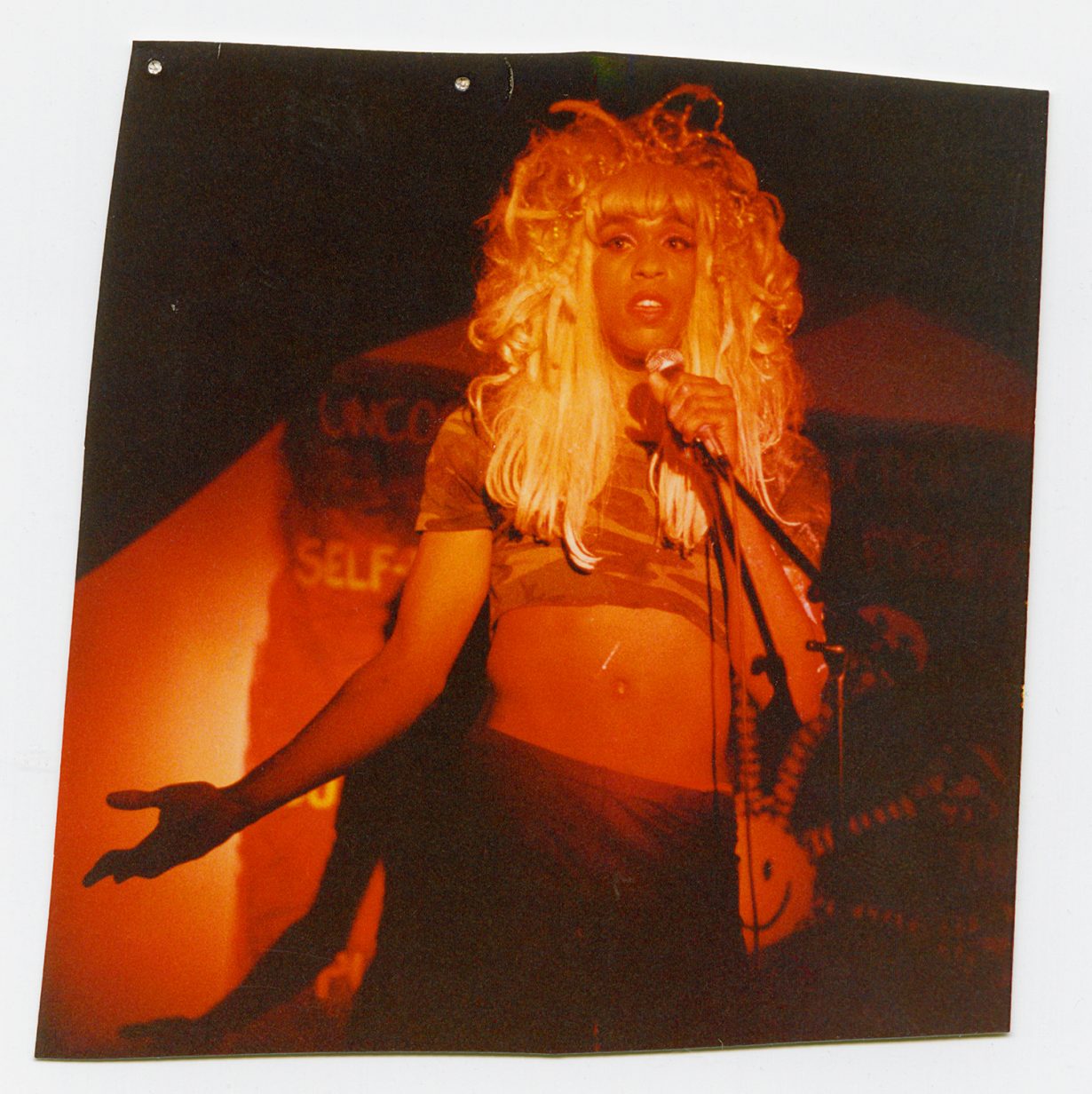

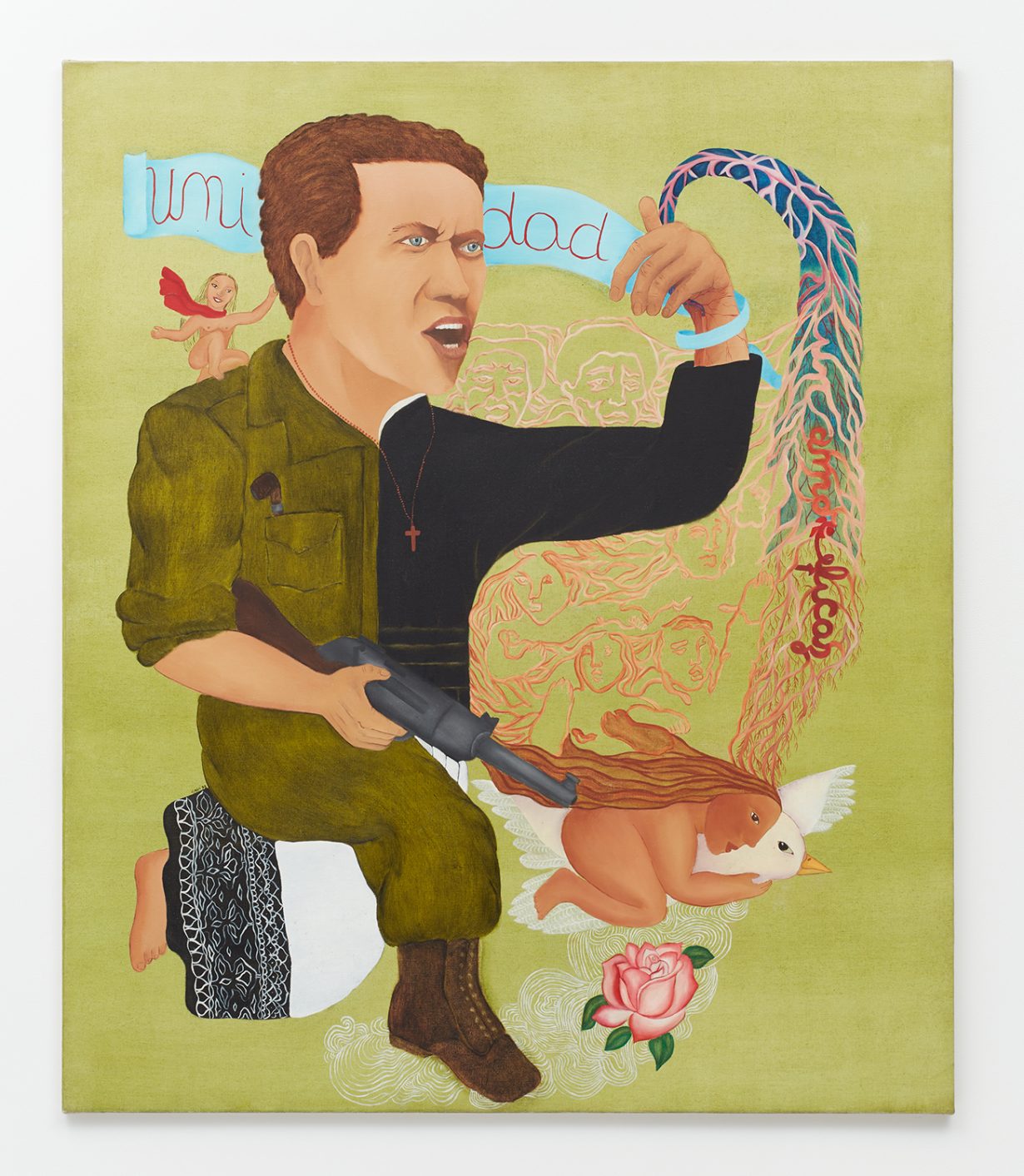

Solidarity is the bridge. It’s a shared language. It is not a prosthetic label. We’re narrating through certain interweavings and lived experiences that proclaim and act in catalytic ways. We are also thinking about the role of militarism in the present and the way that militarism is silencing vivid modes of being and certain breathing bodies in the world. For instance, we have the work of Cecilia Vicuña attuning to solidarity and militarism in relation to Chile and Vietnam in the 1970s. Then in another part of the exhibition, you have the works of Vaginal Davis and Jacolby Satterwhite among others navigating the inheritances of structural violence and enslavement of the Black body, but also queer desire, punk aesthetics, refuge in chosen kin, and radiant love.

DA Every floor has its own subnarrative, there’s a whole floor that explores militarism, queer desire and the hybridity of pleasure beyond disciplinary logic, another floor on hybrid relations between human animal and plant intelligence, and there’s a whole matriarchy in motion focus. They are not really separate in their own logic but constantly connecting back and forth, with entanglements between new and old works, as well as historical loans in the Biennale hall and external venues. At the Gwangju National Museum, we are unfolding a dialogue with conceptions of death and the afterlife, reparation of spirit-objects, corporeal limits of the body as well as acts of mourning.

The 13th Gwangju Biennale, Minds Risings, Spirits Tuning, is on show from 1 April to 9 May 2021