You thought art was a space of freedom? You need to stop thinking and open your eyes

Forgive me, father, for I have sinned. The other day, I went into a big-box DIY emporium fully intending to buy some screws, but in the maze of strip-lit aisles I entered some kind of fugue state and emerged screwless, somewhat unscrewed and toting a bagful of off-brand paints, pencils, sketchbooks and readymade canvases. Back home shortly after, and for the first time in a couple of decades, I was making ‘art’. Inevitably, it was crap. But one thing made me happy about the improvisatory, bean-stalk-like things I drew: I didn’t have to explain them using words. Unlike at art school, where in paranoid preparation for studio crits I, like many of my coursemates, had made the mistake of filling notebooks with airless explanations of what my artworks ‘did’ before I’d even executed them – and suffocated whatever was there in the process, allowing for no spontaneity or surprise – there was no pedagogical judge standing in my studio, or rather over the dining table. And, needless to say, no gallery needing a press release.

In other, um, words: no requirement to do what the artworld is currently set up to do, ie filter the numinous experience of art through language. Yes, I am a critic. I derive my livelihood from pasting words onto art. I see the potential contradiction. But I’m not arguing against interpretation; just against the prison of priming.

Here’s an extremist case (and stop me if you’ve heard, or seen, this one before): in a Berlin gallery a few years back, this fly on the wall saw a bunch of art students walk in. Almost without exception they picked up the handout at the door and scanned it, got the gist, without even glancing up at the show; next, they walked round the gallery holding up their phones, photographing each work in turn, and left. OK, maybe they were on assignment, critical-writing practice; maybe it was their ninth exhibit of the day. But, crucially, at no point did they have a remotely unmediated experience of art. They’d been prepared to think in a certain way by anxiety-defusing interpretation present at the outset of the show, and then they saw what the work looked like through their screens, adding diminishment to self-inflicted confirmation bias. And this is the cartoonish version of what most of us do when we look at art.

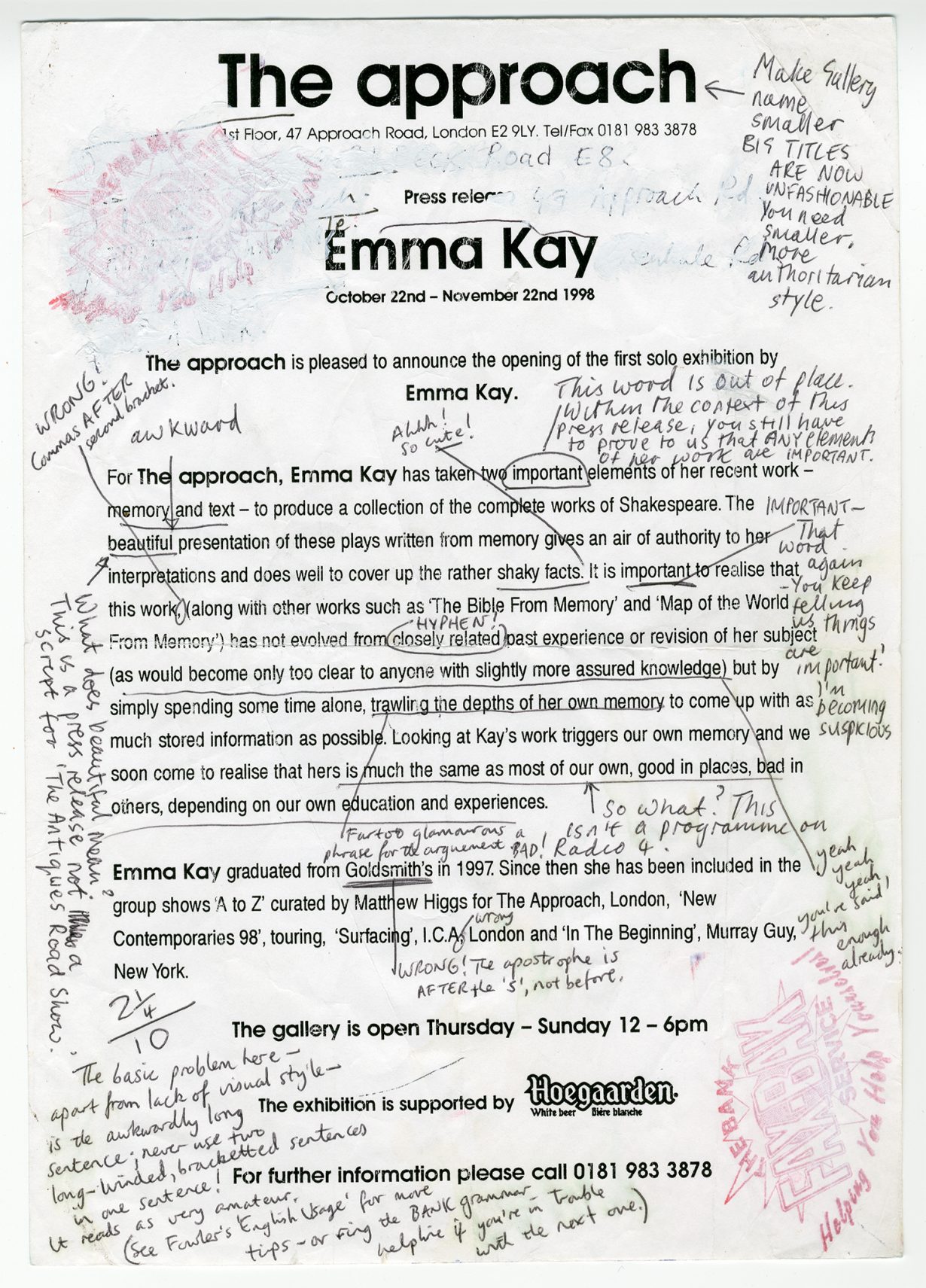

I’m not enough of an art historian to know when exhibitions began to be accompanied by explanations. I suspect that the intersection of ‘this is what this is’ and ‘this is what it means’ dates back to first-wave Conceptualism and the very notion that art was up for being grasped by means of the intellect alone. In recent times, the inevitability of an accompanying crib sheet – or, more highmindedly, ‘textual supplement’ – has reshaped and distorted art itself: codified works featuring nested allusions just wouldn’t perform without an unpacking of their cleverness. When an artist gets away with presenting an unadorned experience, it’s rare; it takes work, stratagems. A friend told me about watching Trisha Donnelly install a show, and her technique in getting what she wanted. The gallery wished to add labels identifying the works, which for the American artist was already too much breeching of speechless sanctity, never mind a press text. Faced with that, Donnelly dejectedly said: ‘You’re just going to make me take them down again’.

It’s not necessary to recap the comedic, pretentious side of the language around art, or the double bind for writers and audiences per se. Some critics I know make a point of never reading the press materials, or at least they assert as much; but some artists nowadays are banking on your doing so. The least-worst strategy is to look at them last. The smartest response to the tyranny of the handout I’ve seen – ironically, I can’t remember who did this – was a show that ended with one A4 sheet pasted to the wall, upside down. Until then, you were travelling via your own lights. Getting used to that is almost a form of detoxing, because language can become a form of addiction, one you might recognise if the first thing you do each day is reach for your phone, scan your socials or the news. It’s a way around the effort of having to think for yourself, or simply be alone with your thoughts, your guesswork, your raw experience.

I own a lot of digital music, more than I’ve ever familiarised myself with, which means that if I throw my iTunes on shuffle there’s a chance it’ll bring up something I don’t know. Sometimes, that what-the-hell-is-this space of unanswered doubt can be downright thrilling; I’m not hearing sonics through genre, or through my prior associations with the artist, or through the cult of personality that has its own distorting effects on art. I’m – almost – just hearing sound, tailored broadly to my tastes but beginning to escape them, and it’s richer. Almost inevitably, if I check who it is, there’s a vague sense of reduced bandwidth, of things snapping to the grid of categorisation, different aspects foregrounding themselves. Without it, conversely, there’s something akin to the child’s preverbal apprehension of the world, direct engagement. Visual art can be a space for that too, if you’re lucky enough to find something genuinely exploratory and if you don’t allow yourself to be spoon-fed from the get-go. Art is already a speech act. Let it be untagged. At least for a while.