Courtesy the artist and Nome, Berlin

Cian Dayrit, born in 1989 to a middle-class family in Manila, creates socially engaged art that aims to challenge and subvert the practices that have resulted in the systemic imbalances that plague Philippine society. Within the Philippines, the peasant (magsasaka) sector comprises 75 percent of the population, according to Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo (Artist Alliance for Genuine Land Reform and Rural Development, or SAKA); this includes groups whose livelihoods primarily depend on food production – farm-workers, fisherfolk and the indigenous minority. Through community engagement, Dayrit and his collaborators – craftsmen and local community members – piece together overlooked spatial, temporal and personal narratives of the oppressed via multimedia artworks and installations. He is, however, best known for his ‘counter-cartography’ textiles – large, handsewn maps of existing geographic regions that inspect and subvert power structures. ‘I wanted to challenge the perspectives that somehow monopolised the framing of history and heritage,’ he told A Magazine Singapore earlier this year.

When the Spanish Jesuit priest and cartographer Pedro Murillo Velarde created the first map of the Philippines, in 1734, he had the help of two Filipinos, engraver Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay and artist Francisco Suárez. Known as the Murillo Velarde map, it engendered an oppressive feudalist system that continues to shape the ways in which land is distributed within the Philippines to this day. Today the country’s oligarchical system ensures that only a few landowning families retain the majority of ownership while millions of peasants labour to produce harvests from which over 75 percent of the produce goes to the landowner. For decades, politicians have made promises of agrarian reform and land redistribution with little success.

Former president Corazon Aquino introduced the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program in 1986, which promised extensive change but has yet to make any meaningful impact.

During Rodrigo Duterte’s 2016 election campaign, the candidate promised to revive the long-dormant Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) and redistribute land to farmers – it’s a promise that, according to the governmental Philippine News Agency, he has successfully fulfilled by allocating 516,000 hectares among 405,8000 farmers as of August 2021. Shortly thereafter, the Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (Peasant Movement of the Philippines, or KMP) released a statement saying that ‘DAR only pursues the distribution of government-owned lands and public lands while safekeeping vast private agricultural lands and haciendas still under the ownership and control of local landlords’ and that ‘the DAR-to-Door program is no more than a counterinsurgency program meant to dissipate farmers’ united struggle for free land distribution and genuine agrarian reform’. The KMP maintains a list of the over 300 peasant leaders and workers who have lost their lives fighting for change under Duterte’s lethal administration.

Dayrit was drawn to activism during his days as an undergraduate studying painting at the University of the Philippines, when he began protesting tuition-fee hikes that occurred just as the Gloria Arroyo administration (2001–10) allocated significant portions of the national budget to military and counterinsurgency enterprises within the provinces. It was, he said when I spoke to him recently, the first time he heard the term ‘extrajudicial killing’. His current practice continues to develop in response to the nation’s politics.

Dayrit was a founding member of SAKA, which formed in 2017, one year after Duterte took office. During that first year, the president’s violent war on drugs had claimed the lives of thousands, and the policies he promoted within the peasant sector under the guise of development continue to subjugate the majority of Filipinos.

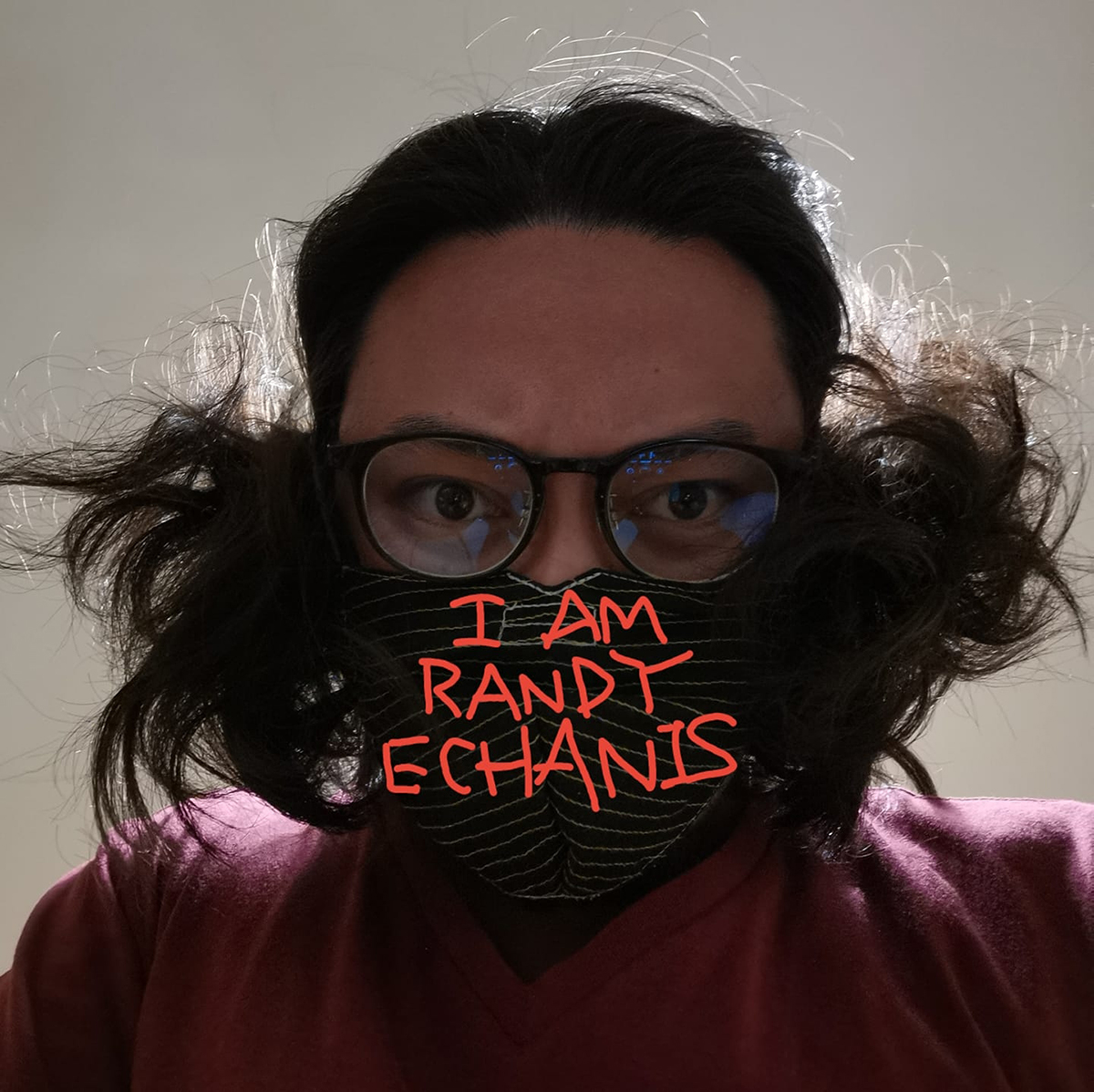

This past August, SAKA launched its online protest campaign ‘We Are Randy Echanis’ with Artista ng Rebolusyong Pangkultura (Artist of the Cultural Revolution, or ARPAK) to commemorate those killed in Duterte’s reign of terror and the one-year anniversary of the death of Randall Echanis. Police forces killed the longtime KMP leader and peasant-rights activist in his Quezon City home on 10 August 2020. The campaign’s premise was simple: members of these collectives photographed themselves wearing masks with the words ‘I am Randy Echanis’, conveying the bold message that Echanis’s legacy lives. In Dayrit’s self-portrait he wears a black embroidered mask as he intently glares through his black-rimmed glasses at the camera lens. His long hair, partially secured by his mask’s strap, frames his face; ‘I am Randy Echanis’ is digitally imposed over his mask. This image appears frequently in Dayrit’s social media as his profile photo, acting as a reminder of Echanis’s brutal death and Dayrit’s own convictions. The added dimension of the Philippines’ ‘anti-terror’ censorship imbues a degree of risk within these self-portraits, as these partially covered visages indicate authorship and make those who wear them susceptible to inquiry. The members of SAKA write, ‘We are also one with the people in demanding for just and lasting peace. But [as] long as feudal landlords deprive the peasantry of rights; as long as the bureaucrat capitalists maintain this dismal status quo by clinging to imperialist powers – there will be no real justice. And as long as there is systemic oppression and persecution; we will utter the words from Ka Randy’s verse: #HindiNaminKayoTitigilan We will not stop! Justice for Echanis, justice for all!’

At a recent conference hosted by the Transnational Coalition for the Arts, Dayrit presented on behalf of SAKA, saying that ‘the peasantry is the mass-based and primary force fighting for sovereignty, democracy, and social justice – and it is in this context that SAKA exists… It has developed into an anti-feudal alliance of art, culture, and knowledge workers who support and advance the peasant agenda for genuine agrarian reform, land development, and food security.’ These words echo in the foundations of Dayrit’s own artistic practice, as he told A Magazine Singapore: ‘Activism taught me that by learning from and putting to the fore the narratives of the deliberately silenced marginalised sectors, social justice can be realised’.

Courtesy the artist

The audience for Dayrit’s multimedia artworks is often the community with which he collaborates: their narratives inform his practice. His involvement with activist groups allows him to gain insight into and share in the issues that plague them firsthand. As part of Busis Iba’t Ha Kanayunan (Voices from the Hinterlands), an exhibition in Makati City resulting from his 2017–18 residency at Bellas Artes Projects’s outpost in Bataan, Dayrit developed a timeline mural of the local Ayta history in the province based on oral histories, interviews and historical sources collected from the Ayta community. The Ayta are a group of Negrito people indigenous to Luzon, thought to have been the earliest inhabitants of the Philippines. However, centuries of oppression have displaced them from their ancestral lands, which are often subsequently destroyed in illegal logging, mining and slash-and-burn farming. Dayrit sprawled these significant moments narrated to him into a horizontal display of these chronologies, his distinct handwriting – which can be seen across other works – also recording incidents of land-grabbing and encroachments on ancestral homelands.

He told GMA News, in Filipino, ‘Like any other indigenous community, they have been pushed to the peripheries of society. Land-grabbing, red-baiting, harassment of armed forces, they’ve been exploited. I just could not ignore the Aytas…’

Building upon this research and further informed by current events, Dayrit’s Valley of Dispossession (2021) maps the region of Central Luzon (which includes Bataan) in a large cartographic textile embroidered with geological features, provincial boundaries and areas of hegemonic ravage. The map’s legend in the bottom right corner explains the various abuses of land and people; gold talismans embossed with bullets or burning bahay kubos (nipa huts or indigenous stilt houses) indicate military presence; gold talismans with tree stumps or sombreros indicate aggressive development projects and/or largest landholdings; and gold stars indicate Chinese landgrabs – particularly referencing the West Philippine Sea dispute. Red bloodlike stains illustrate the mining tenements that riddle the coasts in particular. A central banner towards the top of the tapestry reads, ‘Peasant and Indigenous Struggles in Central Luzon Philippines’, flanked by a haloed farmer on the left and similarly haloed archer and child on the right. More symbols and words frame the land mass – phrases like ‘Agrarian revolution is justice!’, ‘Land to the tillers!’ and the words of Apo Alipon, a respected indigenous Ayta elder who lived to one-hundred-and-twenty-three and also appeared in Dayrit’s 2018 Busis exhibition, encourage mutual care between community and nature with the intention of highlighting the hypocrisy of the neoliberal, neocolonial and semifeudal systems of power that have devastated these lands. qr codes stitched around the textile lead to videos, reports and data gathered by human rights groups in a time and country where the government cannot be trusted. The various layers of Dayrit’s composition visualise the synchronous forces that continue to oppress the overlooked peasant majority.

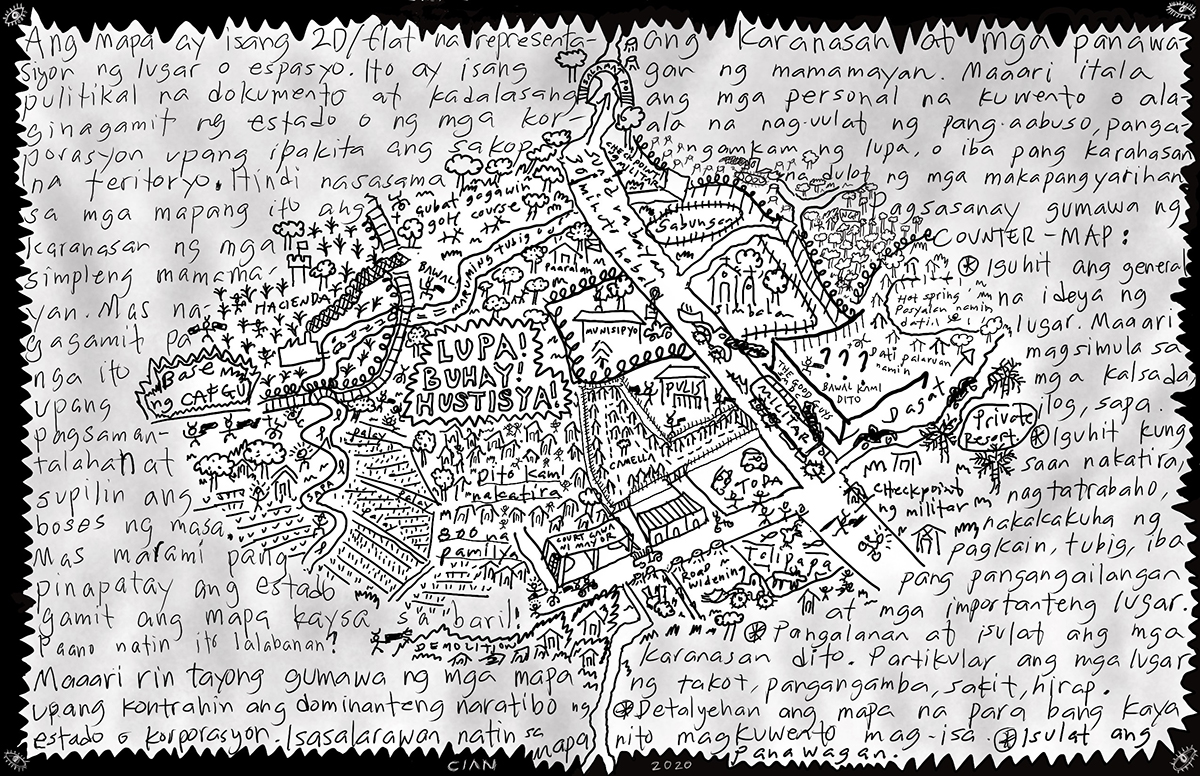

As part of his social art practice, Dayrit hosts counter-cartography workshops with these marginalised communities, in which he encourages participants to create their own counter-maps. He hopes these programmes will encourage communities to reevaluate their spatial narratives. In a text entitled ‘Counter-Mapping for Resistance and Solidarity in the Philippines: Between Art, Pedagogy, and Community’, Dayrit and his academic coauthors write: ‘These projects may rupture rigid cartographic narratives of city projects and regional masterplans by exposing contested histories, relations and bodily experiences that have been silenced for the sake of particular notions of progress and development’. In one example, from a 2017 workshop in Zambales, community member Johnny Basilio draws his hometown, San Jose, Tarlac, with clear military occupation – on the bottom right, he writes, in Filipino, ‘…we are ready to fight for our ancestral land for the next generation’. Basilio’s counter-map demonstrates this hands-on community approach is productive and educational, emboldening and exposing Basilio to the structures that affect him and his community. Over the past year, while confined to his home, Dayrit wanted to make these instructions accessible to more people and developed Pagsasanay sa paggawa ng isang counter-map (Instructions on How to Create a Counter Map, 2020) for the geographical activism collective kollektiv orangotango’s book This Is Not an Atlas. In the centre of the page, Dayrit has drawn an imagined landscape with roads, buildings, trees and farmlands, which juxtapose a large text, ‘Lupa! Buhay! Hustisya! (Fight! Live! Justice!). Text wrapping around the central drawing includes instructions on how to make a counter-map, such as ‘Draw your general idea of the space you occupy. You can start with roads, rivers, creeks, lines’ and ‘Label and write your experiences here. Particularly the spaces of fear, pain, others.’ These instructions, Dayrit explains in the drawing, ‘narrate our personal accounts of abuse, land-grabbing and other forms of aggression perpetrated by the so-called authorities’.

Since 2016, Dayit has worked closely with Henry Caceres, an embroiderer whose family business is based in Pasig Palengke. Where Dayrit draws the maps onto the textiles, Caceres embroiders these traces and, in a playful joke, is credited as ‘Henricus’ in the work. Regardless of the medium he uses, Dayrit ensures a large portion of each sale is returned to the groups he collaborates with and learns from. Lately, however, Dayrit has become increasingly aware of his own complicity within the global market, expressing, when we spoke, his doubts regarding the art object and its disappearance from the communities it depicts and intends to serve once it is bought or institutionalised abroad. As a result, the artist is embarking upon a master’s degree in geography at his alma mater, with the hope of mapping out new ways for his current practice to be more engaged in the communities he serves: “If anything, I’m looking to gain a more structured approach to effectively analyse networks and spaces in which power is used or misused. I’m also looking to adapt existing methodologies while developing new ones that respond to the needs of marginalised communities,” he says.

Work by Cian Dayrit will be included in rīvus, the 23rd Biennale of Sydney, on view 12 March – 13 June 2022

Marv Recinto is a writer based in London