“In our preoccupation with mediating the world, many arbitrary distinctions were drawn, and perhaps they were drawn a long time ago”

Isabel Nolan’s artistic practice is an expansive one in terms of media, scope of reference and intent. The Dublin-based artist’s formats include painting, drawing, figurative and geometrically patterned rugs, angular metal sculptures, photographs and writing. The cast of characters who populate her work includes metaphysical poets, fictional mobsters, millennia-old totemic sculptures and our planet’s sun, which Nolan prefers to paint as near the end of its life. That luminary emphasis is appropriate for her constellating model of meaning-making, which combines anti-authoritarianism, a related interest in looking at Western culture in subjective ways to glean new readings from it and a deep ambivalence about humanity, its relationship to the rest of the natural world and our future on the planet, articulated through absurdism and melancholy and compensatory beauty and tenderness. Recently, Nolan took time out from installing her latest show – at Château La Coste, Aix-en-Provence – to discuss how her art’s many moving parts fit together.

Don’t Look Up

ArtReview One thing that characterises your work, across its stylistic diversity, is an interest in what one might call ‘downwardness’ – from floor-based sculptures suggestive of chandeliers to paintings of lowering suns, photographs of feet, use of rugs as a medium and beyond. Can you say something about why?

Isabel Nolan I guess it’s to do with noticing a preoccupation with verticality and the veneration of height and light in Western culture. In the history of art, in politics and in religion, power is represented and articulated through motifs that represent ascension or elevation as the ideal state for humanity. It’s in the story of Plato’s cave, of Hades and Olympus, of Hell and Heaven, the Great Chain of Being, even in scientific writing. I felt like every text I would go to, or everything I was looking at, it’s the same pattern always telling me I ought to be impressed by height. Likewise everything that is ‘good’, be it divinity, power or reason, is generally correlated with light. These binaries of light/height are good, and darkness/lowness are bad, seem pervasive. It’s so familiar, it’s easy to forget how strange it is that these metaphors are powerful. They shape the way we understand reality, so introducing contradictory or oppositional impulses is a way of unpicking these tropes, visually disrupting something generic and positing the lowly, the imperfect and the indistinct as beautiful. It’s different to valorising abjection but probably shares some of the same desire to disrupt, to make space for other ways in the world.

AR You seem to practise looking askew. When you photographed the deathbed statue of John Donne in St Paul’s Cathedral [For ever and ever, and infinite and super infinite for evers, 2015], for example, you zoomed in on his knees, and later wrote about their ‘ordinary fallibility… yielding a little to gravity’s sickly pull’.

IN In part it’s just a response to what I’m drawn to. That statue in some ways looks unremarkable, holy and reverential, but the knees really attracted my attention. They’re a bit bent, quite knobbly, and I thought about them for years after I first saw them. I love cathedrals, though I find their raison d’être very problematic, so finding something like the statue is perhaps a way of mediating or even mitigating my own interest in this stuff. A way of being interested in St Paul’s that’s more complex than simply saying it’s beautiful. I’m not a historian, not a researcher in any kind of systematic way. It’s much more intuitive and irresponsible, and hopefully the work communicates that my attraction to this stuff isn’t necessarily predicated on the story it’s supposedly telling us. That other ways of looking at this material and engaging with the culture are interesting and nuanced and suit my own sense of how confused things are, that beauty is complicated. It’s also to do with putting the body back into these histories – or maybe materiality. That statue is very sensual, his lips are so inviting and the folds of fabric between his knees look labial. There’s also an antipathy to dirt and decrepitude, the fact that bodies age and can let us down. It’s often occluded in so-called high culture and made into something disagreeable and shameful.

AR You’ve focused, relatedly, on feet numerous times, as in the various photographs of tomb statues’ feet, animals’ paws, thorn-puller statues and pedestrians’ shoes in Curling Up With Reality [2012–17].

IN There seems to be an idea that the foot is a rather unpleasant part of the body. I suspect that prejudice is just to do with it being our point of contact with the surface of the world. Take the tradition of foot-washing in the Christian church – it was practical and welcoming, you’ve been walking for days in sandals or travelling on a donkey and your host offers to wash your feet – but it’s also a symbolic gesture, tending their tired, dirty feet is a way of humbling yourself before a guest.

Or you know, in ballet, dancing en pointe, it’s escaping gravity – decreasing your contact with the ground is exalted. Metaphorically there’s a powerful connection between the material world, earth, death, horizontality and decay – that’s the realm of feet. In Western painting and statuary I think you don’t see the soles of people’s feet unless someone’s dead. Also architecture rarely invites you to look downward at itself. Surveying from a vantage is different. I thought about it a lot when I spent time in Vienna, it’s such a grand city and people there seem very proud of that, but often the pavements are a mess, which just tickled me. So when I did a show there I made a work that required people to look down. Dogs’ paws I just love. If they’ve been out for a run on grass or sand, their paws smell amazing.

Historical Crushes

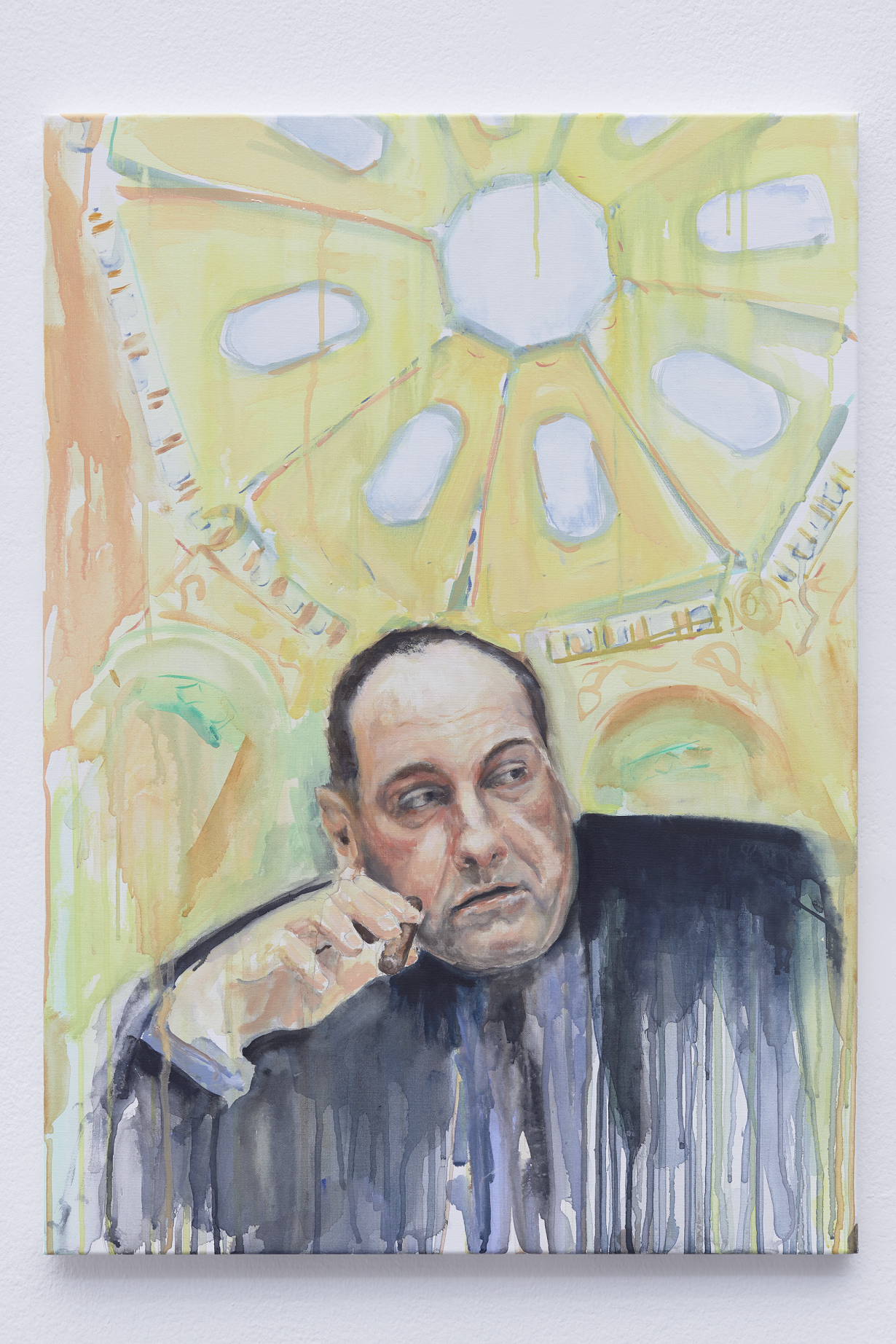

AR The aforementioned Donne might be considered one of an alternative pantheon, a clutch of figures who’ve shown up in your art, including Paul Thek, Simone Weil, Giordano Bruno and the fictional mobster Tony Soprano, who you painted standing in Vienna’s main art museum, not looking up at its dome. What attracts you to these figures, what connects them?

IN In some ways they tend to be outsiders, but outsiders shaped by institutions that cannot encompass them or their beliefs, their desire to make a different world. So there is attraction and alienation in the relationship they have to the systems they’re invested in. Their convictions are often strange to me, their commitment is extreme and they went about trying to implement their ideas in very public ways. Mostly they’re driven by a desire to make a better world – but they’re bloody-minded, they annoy people and so often they’re thwarted, yet they live, or lived, with a conviction that’s utterly compelling. Their desire or their beliefs and their world don’t correspond, and that dissonance has a lot of pathos. It’s quite beautiful, the striving in spite of… I think being both recalcitrant and thwarted is important to creativity. Tony Soprano is a bit of an exception. He was the villain in my pantheon, I put him in the Kunsthistorisches museum because he despises art. He’s a psychopath, an arsehole, but incredibly charismatic. From the first episode of the show he’s trying to angrily reorganise the world, his drive and conviction are compelling, but he’s thwarted too, by his anxiety, by his perverse desire for an American dream that’s passed.

AR How do you choose, or come to, these people?

IN There’s no methodology, I’m drawn to certain subjects and time periods, and to people with belief, scientists too, but it’s largely happenstance. Somebody mentions someone, I read something, and then there’s a lot of invention and projection in the way that I work with the past. Sometimes I read a lot about them or their work but I’m not thorough. It’s often like having a crush, getting excited and preoccupied by a person, imagining all sorts of sympathies with them. They become a way for me to tell a story, or to make something that speaks to the contingency of history.

AR The people you focus on tend to be independent thinkers, often falling outside monolithic systems of thought, questioning consensus reality. Looping back to antiauthoritarianism, do you have a sense of where your own comes from?

IN Hmm. I’ve read a lot since I was very small, and back then I think if you grew up reading, and reading a lot of fiction, you learnt early on that there’s a lot of ways of looking at the world. Growing up in Ireland, the conflict in the north was perpetually in the news. So you learnt about Irish history and colonialism very early on. There was no divorce, no birth control, no abortion, homosexuality was still to be decriminalised. Something like 97 percent of children in the country went to schools run by Catholic religious orders. The church was venerated, though I was fortunate not to have particularly religious parents. Then the cracks appeared, important and devastating stories came out about the church.

My mam provided a feminist perspective on things. As a kid she couldn’t get the schooling she wanted, married young, was compelled in so doing to give up her job, had four children and realised that this wasn’t the best deal. She was probably teaching us to read before we could walk. Education was everything at home – she got herself to university in her fifties, eventually getting a PhD. I think it’s that simple. I was implicitly socialised into being sceptical, into knowing that there’s always an agenda with power, another way of seeing.

Remaking the World

AR In that respect – looking at historical materials, perhaps rewriting their narratives or bringing out latent aspects – I’m thinking about your recent works involving and invoking an ancient sculpture carved from a mammoth tusk called the Löwenmensch, another example of ‘upwardness’.

IN It’s a beautiful object, the earliest sculpture that we have from the Paleolithic period, it’s dated to 38000 BCE. It’s a hybrid creature, a human torso and legs, and a lion’s forelimbs and head. I’m fascinated by the decision to combine the uprightness of a human and the ferocity, the mentality of a lion. It interests me to think that this is a moment when humans began to remake the world for themselves, and not out of necessity perhaps, but for more abstract or imaginative reasons. A thing that doesn’t exist, someone carves a tusk and now the world is different. That impulse to reformulate the world by physically changing material is fundamental to us as a species.

AR You’ve suggested in the past that it relates to mankind separating itself from nature, which could be read as having profound reverberations down to the present.

IN Looking at it today, it looks like an object that embodies a nature-culture debate, but we have no idea why it was made or what beliefs the maker(s) had. I’ve written about it as possibly predating that Western sense of human exceptionalism, of our special separation from the rest of nature. It seems to join the earth and the sky, the human and the animal. The title of one of my lion-human rugs is Löwenmensch – spanning earth and sky for forty thousand years (2018). But in our preoccupation with mediating the world, many arbitrary distinctions were drawn, and perhaps they were drawn a long time ago.

AR You’ve been painting saints recently, and St Jerome and St Paula appear in your current exhibition at Château La Coste. What’s your interest in such figures, beyond their relationship to lions (and lion’s paws)?

IN My interest in them is more generic than with the aforementioned people. We have the historical evidence and the bonkers elements of their hagiographies, fabulous details like St Columcille prophesising correctly that an inkwell would tip over in the afternoon, or saying that he could see behind himself. Their stories involve making sacrifices, overcoming adversity, successes, falls and ascensions, etc. They follow and feed exactly the same metaphoric veneration of light, height and of course, though I didn’t flag it earlier, masculinity. As figures they also bridge interior and exterior worlds in a way I find fascinating – it’s the thinkers I like. And it may seem archaic but Jerome’s, and the largely forgotten Paula’s, translation of the Bible influenced Western culture profoundly. St Columcille changed the course of British history with the founding of his monastery on Iona.

As well as the saints, the show at Château La Coste has a lot of imagery of waves and fish, of microscopic phenomena, passage-grave motifs, figures from Greek myths and dissolving suns, a lot of suns. It relates to something that we haven’t talked about, a preoccupation with the movement not just from high to low, past to future, but also from intimacy to vastness – I need pinpoints that allow me to look at long timespans. The paintings and rug are all to my mind set in different eras, the imagery is disintegrating, a lot of dripping paint. I want them to thrum. Space, sky, sea, sun and earth bleed into each other. Then there’s just one sculpture, it’s trying to take up as little space as possible, but still shape the world around itself.

Catastrophising, Drifting

AR A long-term preoccupation for you has been extinction, whether in numerous paintings that seem to depict the collapse of the sun at some future point [e.g. Some time later the sun died, 2014], or even in that sense of a gravitational pull downward in so much of your work. For someone who’s resistant to didacticism, do you think your art engages with ecological issues?

IN Like a lot of other people, I find what’s happening quite fucking terrifying, and it’s hard not to think about that. But there’s a fantastic cognitive dissonance where, unless you’re an exceptional person, you don’t really change huge amounts of your behaviour, you travel less, eat less meat and make shows that allude to rising sea levels, future extinctions and the end of the sun. It’s in the work because it’s in my head. And I’ve always had a catastrophic mind, always thinking that the worst is going to happen at any moment. But the work always escapes my expressed negativity – and I find the scope of the universe, the scale of geological time comforting. It puts everything into perspective. I think that shapes the work, the shows; plus there is a pleasure in making, in resisting that negativity by deciding to keep on keeping on.

AR Because your work does have those consoling qualities – thinking also of your warm colour harmonies – or is structured on antinomies, as when you shift mediums regularly within a single show, it seems that whatever is there, its opposite can also be found. This could again be related to a resistance to a single way of thinking, or telling the viewer what to do. It feels like, in an exhibition of yours, there’s an open-ended conundrum presented, in which some sort of relationship is being posited between many disparate things, but it’s yours to drift through.

IN Yes, there are tensions that animate the exhibitions, contradictions testing those binaries I talked about. Maybe it’s partly an attempt at characterising my own experience, which I could frame negatively as an inability to believe in metanarratives, to be single-minded. I love the word drift, it mimics my way of researching, with the smallest possible ‘r’ that you can put on that. It’s not systematic, more apophenic or something. This thing reminds me of that, connects back to that, and so on… if there’s a worldview, it’s maybe that things are connected. I was writing something very short about Paul Thek recently, it was about dissolving boundaries. And in a way, for me, that’s the work of love. That’s a word I haven’t used yet, but one of the things I’m aware of when I’m working is that I’m trying to love the world. That might sound terribly naff, but being alive is strange and hard, and there’s an awful lot of shit going on. At certain moments when I feel very connected to the world, looking at one of those rare artworks that stop you in your tracks, reading something utterly compelling or whatever, that feels like love. When disparate things start to join up, to make a new kind of peculiar sense, it feels great. There’s something interesting here and some of it we invented it for ourselves, as a way of making being here better, of marking that – sometimes it works.

Isabel Nolan’s exhibition 499 Seconds is on view at Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, through 4 June