There is a fine line between what Abraham Cruzvillegas calls autoconstrucción and autodestrucción. Somewhat grammatically awkward, the former proposition (which might seem like, but isn’t, a synonym for DIY) is the umbrella term under which the Mexico-born, Mexico City-based artist has been presenting and developing his rich and variegated production since 2007 (he has been working as an artist since the 1990s). Seemingly a bit more linguistically at ease with itself, the latter proposition introduces a new phase of the artist’s practice, inaugurated with his December exhibition at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, titled Autodestrucción 1. However, whether the work created under the prefix de radically differs from that created under the con remains to be seen. And that may be the point. Or one of the points. But before getting stuck in the koanlike matter of that philosophical conundrum, perhaps it would be useful to clarify our terms and ask just what autoconstrucción is. And where it comes from.

For Cruzvillegas, autoconstrucción refers to his parents’ home in Ajusco, a neighbourhood to the south of Mexico City, and to the ad hoc method by which it was built. Constructed on notoriously inhospitable volcanic rock, Ajusco was originally settled by squatting families (Cruzvillegas’s included) during the 1960s. These early settlers built their homes not all at once but in phases, adding parts and whole rooms when finances and material circumstances permitted, and with neighbours helping neighbours as needed. Such a progressive, collective and organic way of building ensured that such homes and the neighbourhood in which they evolved were (and still are) ‘definitively unfinished’ – to use a favoured Duchampism of Cruzvillegas. Essentially unplanned, in a permanent state of flux, made with local and/or found materials and rooted in community, this style of architecture was the source of inspiration for Cruzvillegas’s autoconstrucción.

If the political position behind autoconstrucción ever seems unclear, it is because the artist’s dialectical attitude is fully present on every level of the work conceptually, politically and materially. Where most privileged Westerners, who have been culturally trained to condemn poverty, might perceive such conditions as nothing more than an affliction to be endured by the poor, Cruzvillegas sees extraordinary ingenuity, methodology and community-building through building. This, however, does not imply an uncritical embrace of these conditions. Rather, he seeks organically to account for the complexity, ambiguity and potential contradiction contained in any sociopolitical problem. All of which is to say, akin to Ajusco, the so-called definition and even meaning of autoconstrucción, as well as the kind of work generated under its aegis, is in a continual state of expansion.

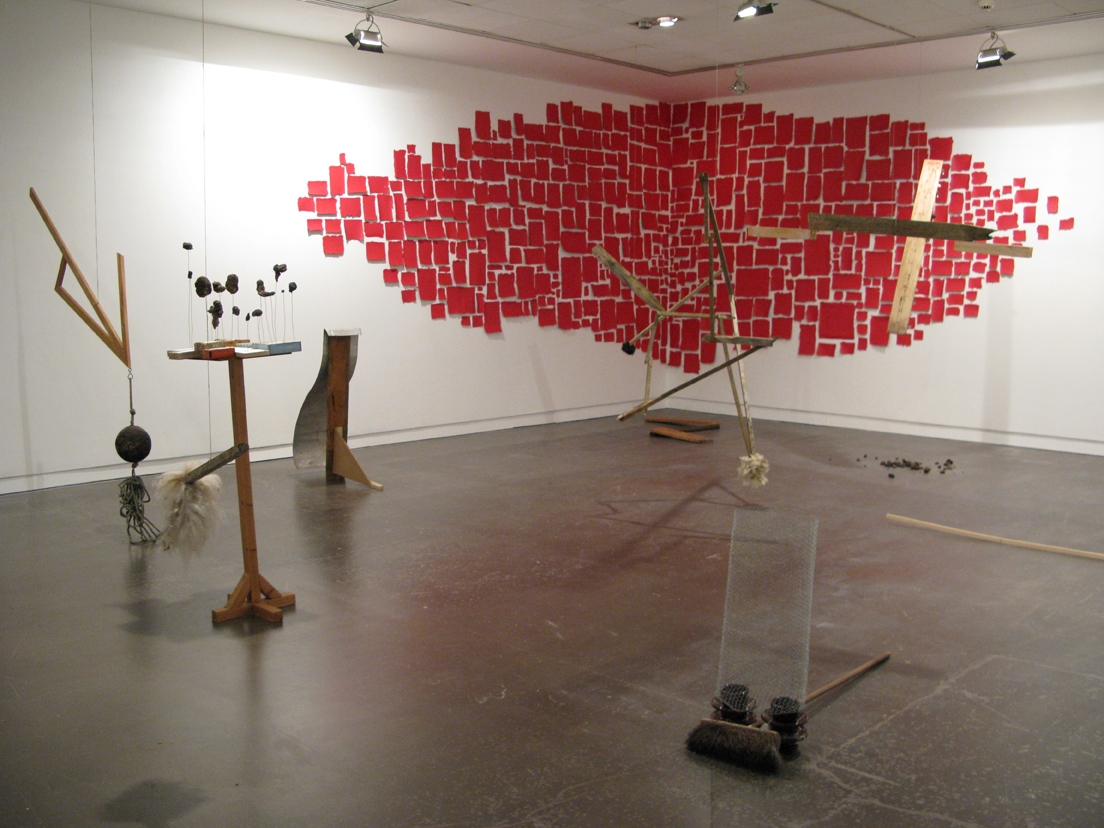

This is precisely why and how, under Cruzvillegas’s auspices, autoconstrucción has been able to manifest in so many guises, places and modes: from small autonomous sculptures to large sculptural-cum-architectural installations; from mobile musical collaborations to an hourlong film, even a play. Autoconstrucción is multiplicity incarnate. Indeed, the term could be said to designate more of a spirit and an ethic than, say, a theory-driven aesthetic. And yet his works are often united by an identifiable formal sensibility, whose predominantly found-object or poor-material aesthetic influence is as indebted to Robert Rauschenberg, David Hammons and Jimmie Durham as it is to Gabriel Orozco. The difference between them and Cruzvillegas, however, is the highly personal, specific and inherently protean programme to which his cultural and material universe adheres. Thus does the freestanding sculpture Autoconstrucción: Departamento de Defensa (2007), which consists of a diminutive totem of wedges of wood stacked one on top of another, with a series of broken bottles glued to the summit, deploy such found aesthetics towards the end of representing homemade security devices as seen atop the outer walls of economically challenged neighbourhoods. Neither a condemnation or affirmation of poverty, such a work celebrates the ingenuity people are liable to bring to such circumstances. The spirit of collaboration and hybridity that informs the artist’s evolving method can be seen in his musical projects titled – any guesses? – Autoconstrucción, at the CCA in Glasgow in 2008, and later, at the end of his DAAD residency in Berlin, The Self-Builders’ Groove (2011).

At the core of both projects were songs the artist had written primarily about Ajusco, produced, in the Berlin project (in collaboration with Gabriel Acevedo Velarde and Sebastian Gräfe), ‘in the space’, to quote Cruzvillegas from the attendant publication, ‘between a punk three-chord strategy, sample dub tradition, rebajada’s slow motion earsplitting, hip-hop appropriation and Tyrolese-Tibetan electro-digital tunes’. In the Glasgow version, a pedal-powered vehicle (evolved from a bicycle) with speakers attached to it, made in collaboration with Glaswegian John O’Hara, roamed the city and broadcast the songs. In Berlin a band was formed by the artist, giving three concerts in different parts of the city (as is often the case with Cruzvillegas’s projects, both incarnations were accompanied by publications, which are not so much catalogues as they are documents of the process, inspiration and community generated by and generative of each manifestation of autoconstrucción).

Cruzvillegas directly portrayed Ajusco in Autoconstrucción (2009). Inspired by a childhood memory of witnessing his parents having sex, the artist created a 62-minute pornographic portrait of his neighbourhood which features four heterosexual couples of varying ages engaged in explicit indoor and outdoor sex, intercut with pans and shots of the buildings, textures and colours that make up Ajusco. Little or nothing to do with a drive to shock, its desire to portray sex links up with the artist’s holistic and inclusive attitude, which registers elsewhere in his irrepressible embrace of marginalised or dissident subcultures.

All but returning to the inspirational roots of autoconstrucción, the most spatially expansive embodiment of the ever-mutating term took place in 2010 at Galerie Chantal Crousel in Paris. Titled La Petite Ceinture (after the wall that formerly surrounded Paris and that geographically, economically and culturally delineated an inside and out), the plastic aspect of this exhibition comprised a large, architectural, circular structure that, made exclusively of found materials such as scraps of wood, was reminiscent of a skeletal favela and filled the entire main gallery space. This unruly object was complemented by a photocopied publication, which featured interviews (conducted by Cruzvillegas) with knitters, community gardeners, slam poets and other figures who issued from a cultural space that was alien to clichés of Parisian identity.

Questions of identity, its relationship to sub- and counterculture, and how it is constructed, inherited and displayed through fashion and subculture have played an important role not only in autoconstrucción but also, it seems, in the dialectical shift to autodestrucción. The first manifestation of it, at Regen Projects, consisted of a series of hanging and freestanding sculptures made of rebar, wire, feathers, jewellery chains, textiles and curing strips of beef, and was heavily informed by the artist’s interest in zoot suiters (or Pachucos, as they are known in Mexico) and their Second World War French counterparts, Zazous – subcultural groups whose rebellious nonconformity was made to visibly register in sartorial excess. As is often the case with Cruzvillegas, the interest has autobiographical roots: his great uncle, who might have been a character in a Julio Cortázar story, was a zoot-suiter jazz musician who ended up in France during the war. For Cruzvillegas, the formation of identity is the product of a complex exchange of paradoxical forces that bring into play both construction and destruction, separation and inclusion, a departure and ultimately a return, full of affirmation, negation and contradiction. This being the case, autodestrucción promises to be as much about creation as it is about destruction, and as such underlines the overall exemplary – to my mind – dialectical complexity of Cruzvillegas’s practice.

While researching this article and reading through the abundance of material and artist writings, I was struck by the following handwritten quotation from Robert Smithson’s Hotel Palenque (1969–72) in the Mexican artist’s Documenta notebook (you may not have noticed him, but he was a ‘participant’, surreptitiously composing colour-coded, ad hoc sculptures every day from on-hand material on the streets of Kassel): ‘Buildings being both ripped down and built up at the same time.’ It seems like a note to self, a sage and compact reminder of the paradoxical nature not just of Cruzvillegas’s work, but of the world in general.

This article originally appeared in the January & February 2013 issue.