A personal letter to the late French master, whose sharp images rendered words unnecessary

I didn’t care about cinema in my youth. It was only as an undergraduate that I began to learn of it as an art form and discover the worlds beyond the Hollywood blockbuster. On my crash course of its history, I was taken by movements that changed its form, from the Soviet montage school to the New German Cinema, via Italian neorealism and the French New Wave. And within each, I admired directors who were Communists, who thought film had the power to change the world but for whom stylistic innovation and personal expression were just as integral to their work as their politics – no matter who that might alienate. Several figures jumped out: Sergei Eisenstein, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and, of course, Jean-Luc Godard, whose imperative to ‘counter vague ideas with sharp images’ struck me as the perfect distillation of what an auteur should strive to create.

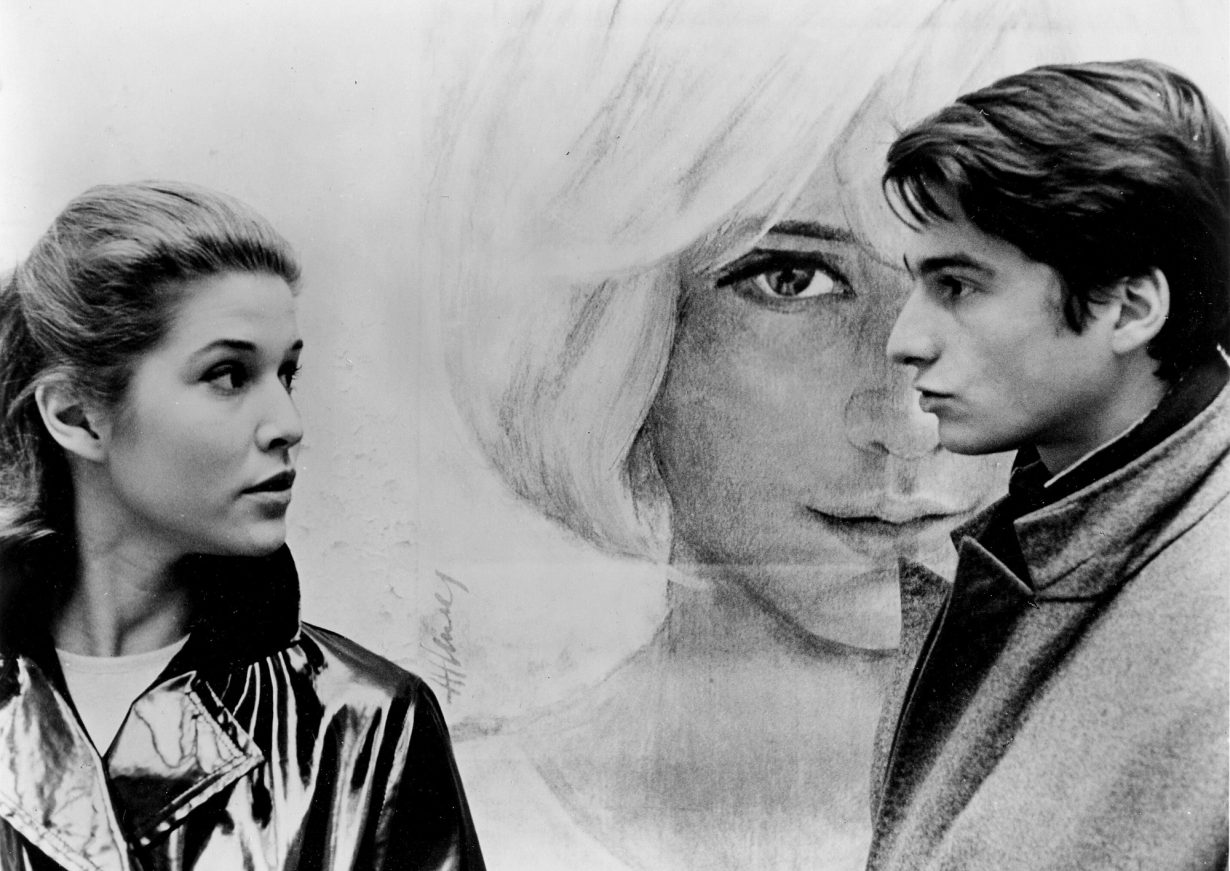

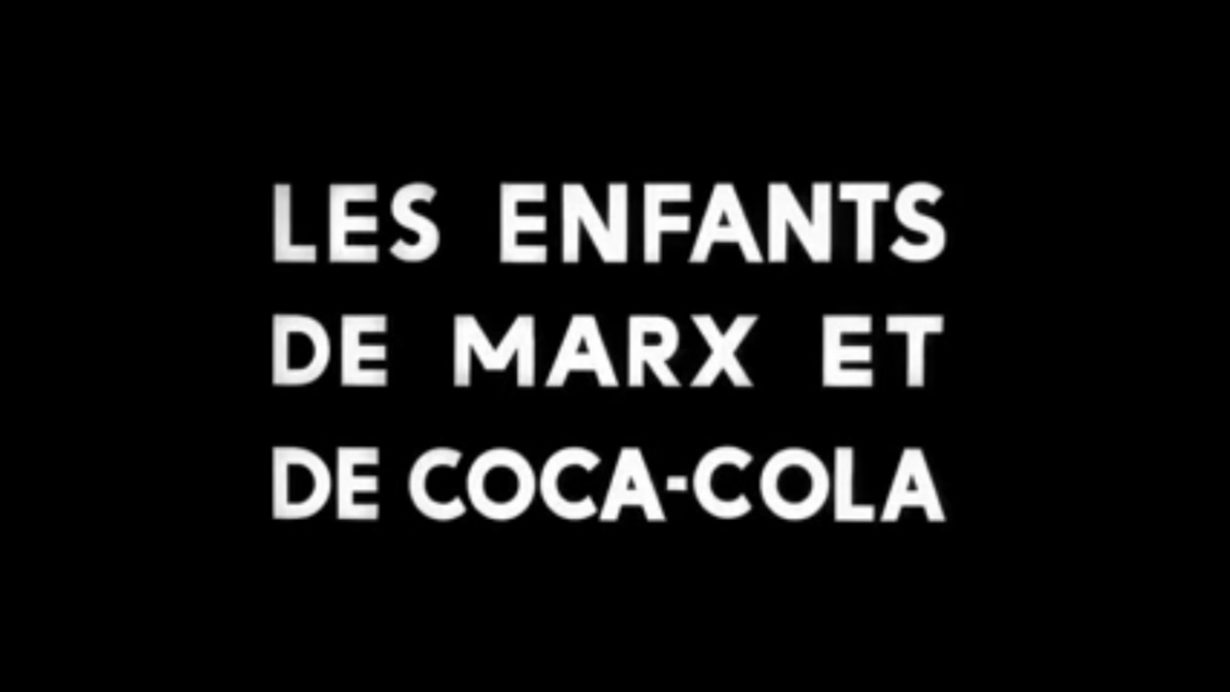

Plunging myself into European film, I was delighted to find that Manchester’s independent cinema, the Cornerhouse, had a Godard season on – and stunned to find this was around a new feature, more than forty years after his first, entitled Éloge de l’amour (2001). By this point, I’d come to feel that most filmmakers did their best work within a decade of their debut full-length work, and Godard’s first years were extraordinary. Always in dialogue with 1960s radicalism without being dogmatic or didactic, his films provoked thought about the difficulties of living a creative, Communist life in a capitalist world, or, as a title card in Masculin féminin (1966) put it, being ‘the children of Marx and Coca-Cola’. Every aesthetic aspect, from the clothes that his leading characters wore to the distinctive font he always used, seemed so unified, but it was the philosophy behind his scripts that made Godard’s images so striking. His searing hatred of capitalism, and of those who did not hate it, vivified that famous tracking shot of a car pile-up in Weekend (1967), condensed into those memorable three words uttered by a bloodied woman crawling from the wreckage: “My Hermès handbag!”

My favourite Godard film, however, was his most mainstream. I first saw Le Mépris (1963) not at the Cornerhouse but at the Odeon multiplex, where cinematographer Raoul Coutard’s Technicolor looked incredible with its vivacious shots of Capri’s blue sea and sky, Brigitte Bardot’s black wig and Jack Palance’s deep red car. I loved the way Godard interrogated his own practice and the power structures of his industry, with his intricate script about an American producer who butchers a playwright’s story for Fritz Lang’s adaptation of The Odyssey. (I especially enjoyed its subtle allusions to the struggles Bertolt Brecht – one of Godard’s heroes, and mine – had in writing for Hollywood.) Like many of Godard’s films, Le Mépris was in part about the inability of people to communicate. It used Georges Delerue’s beautiful theme to devastating effect, swelling into life whenever married couple Paul (Michel Piccoli) and Camille (Bardot) ended an argument. The semiotic link became so strong that towards the end, Godard would use it to signify that they had grown further apart, rendering words unnecessary. Twenty years on (and seven years after the Cornerhouse’s closing in 2015), I still find myself listening to it whenever my relationships break down.

A few years ago, amidst the death of anti-capitalist theorist and friend Mark Fisher, the election of Donald Trump and the march of the global far right, romantic disappointment and ongoing depression, I called the Samaritans. Talking about the biggest pitfall of suicide – that one’s last conscious thought might be to regret the act – I said: “I’m haunted by a film I saw, where the central character straps some dynamite to his head, lights it and then says, ‘What am I doing?’” The volunteer replied: “Is that Pierrot le Fou?” I was snapped out of my despair, reminded of the power of art for long enough to address my mental illness and recapture some enthusiasm for my creative work and political engagement. Maybe his films didn’t change the world as much as he, or I, may have wished, but it’s no exaggeration to say that in that instant, Jean-Luc Godard’s sharp images saved my life.