In joyful, speculative work, the artist unpicks and repatterns mythologies around the depiction of native cultures

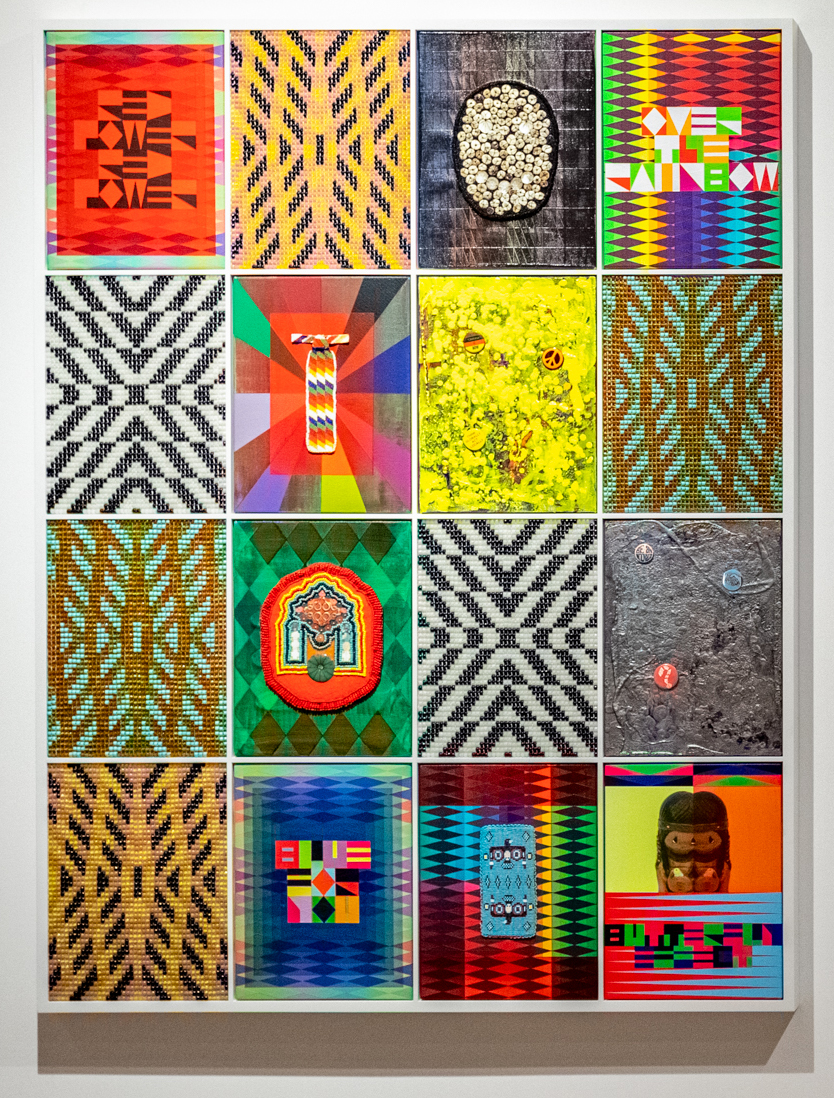

A gridded metal frame on the wall pops with a colourful series of embedded canvases and woven bead patterns. Some of the canvases in They Play Endlessly (2021) bear dizzying geometric designs in bright purples and pinks, on top of which are set small faces made of beads; several feature simplified depictions of Native Americans, one with a profile of a man wearing a feathered headdress, another seemingly a children’s book illustration of a young boy with long hair, held back by a red headband, looking over a grass field. Next to these in the grid, a few canvases spell out statements in chunky, stylised letters: ‘The myth persists’; ‘You’re gonna miss me when I’m gone’.

Myth, play and refusing to disappear: the kaleidoscopic swirl of They Play Endlessly serves as a concise introduction to the work of American artist Jeffrey Gibson, encapsulating as it does his use of painting, craft and collage as means to unpick and repattern what is understood as contemporary Native American culture. The designation ‘American’ is of course a reductive simplification, a convention that belies its long trail; Gibson’s ancestors are of the Cherokee and Chocktaw tribes indigenous to the continent that only relatively recently came to be denominated as ‘North America’, though Gibson himself was raised, and has lived and worked, internationally, coming to be based in Hudson Valley, New York. Nor is his work rooted in a fixed geographical location, and as such it raises questions not so much of belonging but of affinities and proximities. As with They Play Endlessly, it often has an immediate, vibrant punch, whose playfulness belies the knotted layers of history that shape it, with each work asking how we might continually reshape an understanding of what indigeneity is.

The pseudo-quilt of They Play Endlessly, installed as part of The Body Electric (2022), Gibson’s recent solo exhibition at Site Santa Fe, displays some of the persistent mythology embedded in depictions of native cultures: the solemn-faced men in ceremonial costumes, the half- naked naïfs immersed in nature – stereotypes of noble dignity and strength in suffering that arose to paper over the erasure and eradication of native people. Such images still abound in American culture: the kneeling maiden of the Land-O-Lakes butter logo; the Chicago Blackhawks ice hockey team; Saturday morning reruns of Disney’s cartoon Little Hiawatha (1937) – continual reinforcements of native culture as something exotic, other, past. They Play Endlessly also holds some quieter material histories, with many of its patterns made up of a mixture of plastic, glass and crystal beads, as nods to the beadwork that existed in native cultures before the arrival of Europeans during the fifteenth century; the size and shape of traded glass beads, made in Venice and Bohemia, eventually led to changes in the forms and styles of the beadwork being made. And gliding over such stories are the endless patterns and bold statements that feature across Gibson’s canvases, murals, sculptures and costumes; phrases deployed in previous bodies of work had drawn more from dance and club hits of the 1980s and 90s – from Mr Finger’s deep house track Can You Feel It (1986), to Whitney Houston’s It’s Not Right but It’s Okay (1998). Now they increasingly look to poetry and political proclamations, like ‘To feel myself beloved on the earth’, a line from Raymond Carver’s 1988 poem ‘Late Fragment’, or the phrase attributed to Frantz Fanon, via Malcolm X, ‘by any means necessary’: statements that stop us and ask how we might rewrite the present.

Firebelly (2021) is a beaded sculpture of a simplified bird, its red and gold wings flecked with turquoise, its eyes translucent heart shapes. Such sculptures, of various animals and uncertainly human- shaped figures that populate Gibson’s exhibitions, draw in part on his research and work reconfiguring the collections of institutions such as the Newbury Library and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and the Brooklyn Museum, seeing what objects are held in their respective collections as representations of ‘native culture’. Some of these are simply offhand tchotchkes, sold at roadsides and tourist sites; such items aren’t high-end craft but are still framed as tokens of a culture. It could just be someone making what they thought was a nice design, but by virtue of the exchange it becomes a souvenir of the idea of authenticity. As Gibson has put it, he was drawn to how this type of object ‘wasn’t native enough and it wasn’t not native enough’. This statement provides a useful lens through which to consider his work as a whole – as a set of ambiguous props, emblems of a tangled, patchwork culture still in formation, yet to take flight. Dolled up in intricate beadwork and bright kitsch plumes, Gibson’s flamboyant artefacts mock the anthropological impulse, while buzzingly suggesting new rituals: ‘proposals’, Gibson has suggested, ‘for future hybridity’.

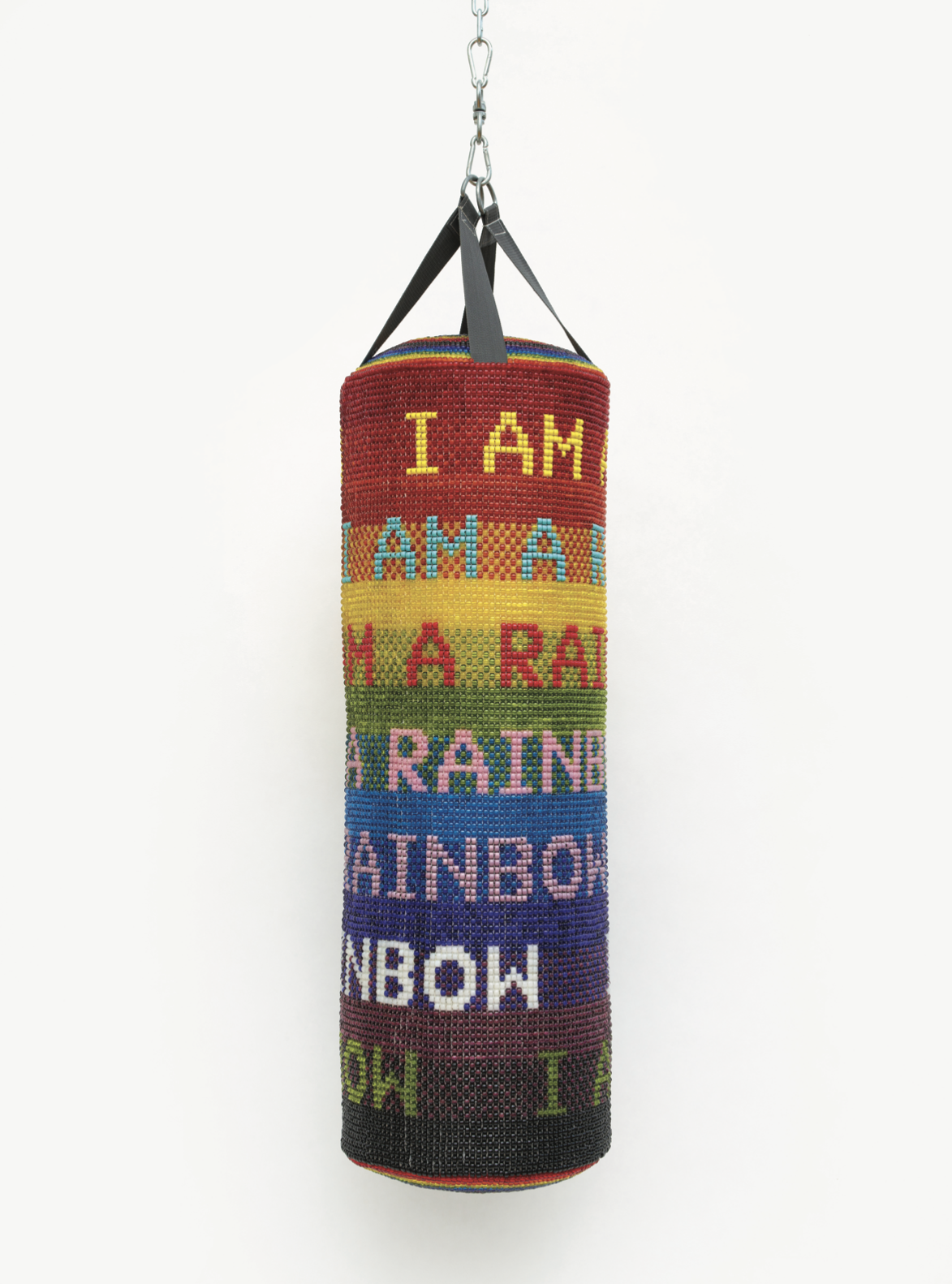

Alongside such figures, hanging from the ceilings are often elaborate costumes and beaded punching bags from Gibson’s long-running series, usually bearing statements of character, intent and energy. On the punching-bag work All I Ever Wanted, All I Ever Needed (2019), the euphoric romanticism of the Depeche Mode lyric (from the 1990 track Enjoy the Silence) takes on a tinge of weary self-acceptance when it is cast in baby-blue beading on a punching bag made up with brown and yellow chevrons with a rainbow skirt, dangling expectantly above the gallery floor. The actions that have been continuously implied in Gibson’s installations – of boxing and weaving, sure, but most often of clubbing, dancing and other rituals of ecstatic movement – have more recently been realised, with works that act literally as backdrops and stages for meetings, discussions and performances.

I AM YOUR RELATIVE, held earlier this year in the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, was an area of moveable seating, the furniture and walls all covered in posters of eye-popping patterns: a space to configure relations and relationships. Stickers that people could place as they saw fit were given out, bearing statements such as ‘Their Dark Skin Brings Light’; ‘They Choose Their Family’; ‘Respect Indigenous Land’. This last phrase was also blazoned across the pastel ziggurat Because Once You Enter My House, It Becomes Our House (2020), a temporary sculpture that sat outside in Socrates Sculpture Park in New York for eight months, hosting events by native collaborators such as choreographer Emily Johnson and composer Raven Chacon. In the performances there, and at others such as Gibson’s exhibition in Santa Fe, performers wore long, colourful robes cut from the same cloth, as it were, as Gibson’s posters and murals, bearing yet more slogans: ‘She Knows Other Worlds’; ‘They Teach Love’; ‘Speaking to the Sky’; ‘She Rewrites History’. These are determined, unashamedly optimistic statements, casting their wearers as participants in an uncertain ritual, enacting a spell that might move beyond scarred histories and reshape what is to come.

In their essay ‘Who Belongs to the Land?’ (2022), indigenous American writer Lou Cornum proposes an Indigenous Futurism that is ‘about the struggle for a different future as well as a distinctly different idea of “future” – one that goes beyond the conflict between tradition and progress, and asks us to inhabit the present’. While Gibson’s neon clubbing-nostalgia and nods to native ceremonial wear draw from the past, it is towards such an inhabitation of an unmoored present that Gibson gestures. In the video A Warm Darkness (2022), created from a performance held around the Our House sculpture, performer Mx. Oops dons a hot-pink hoodie and matching bowl-shaped wig, dancing angularly, happily alone within the scaffolding inside the sculpture. It’s joyful, spurious, obscured. The performance and video cast Our House as a tomb, a place to put things to rest; as well as a haven, a shelter, in which to dance just for yourself; and a site from which our rewriting of the present might take place, a place where, as Cornum puts is, ‘there is no pre-apocalypse or post-apocalypse, only perpetual revelation’.

THE SPIRITS ARE LAUGHING, a survey exhibition of Gibson’s work, will open at the Aspen Art Museum on 4 November; They Come From Fire, a new site-specific installation at the Portland Art Museum, Oregon, will be on view from 15 October to 26 February; a selection of new works by Gibson will also be presented at Stephen Friedman’s booth at Frieze London, 12–16 October