Why can’t the fashion world get enough of the teenage martyr who led her country to victory?

Joan of Arc closed Balenciaga’s couture presentation in Paris this July. Artist Eliza Douglas appeared as the saint in a 3D-printed, 36kg armoured dress made from galvanised resin and finished in polished chrome. The mood of the show was sombre, with models walking at a glacial pace, but Douglas moved with deliberate stiffness. Her rigid skirt tilted back and forth, shiny as a silver saltshaker. ‘I thought maybe if Joan of Arc had worn this kind of armour,’ creative director Demna Gvasalia (known mononymously as Demna) said after the presentation, ‘they would’ve not burned her at the stake.’ If we are being charitable, we can assume that Demna’s intention was not to imply that the only thing standing between a nineteen-year-old girl and her torturous execution was a Balenciaga dress. We can hazard a guess that he was passing comment, albeit clumsily, on the punishment she faced for wearing men’s clothing, with this gown offered as a subversive alternative: conforming to a feminine silhouette without losing those all-important connotations of valour and protection.

Demna is not the first designer to call on Joan. She has long been a figure of intense interest in the fashion industry, an unlikely icon given her ascetic air. Born in the fifteenth century to a farming family, she grew up during the bloody hundred years’ war between England and France. Aged thirteen she began having divine visions that she would lead France to victory. Such was the strength of her fervour, she met and convinced the future King Charles VII to allow her to successfully lead the charge at the siege of Orléans when she was still only seventeen. Other victories followed, precipitating the king’s coronation in 1429. Joan’s reputation became legendary, bolstered by the fearsome image of a teenage girl in armour leading the attack. However, the following year she was captured by the English-allied Burgundians and put on trial for witchcraft, heresy and wearing men’s clothing. In 1431, she was burned at the stake in a public square in Rouen. She was canonised by the Catholic church as the patron saint of France in 1920.

In the imagination of the fashion world, the teenager who led a French army to victory has come to symbolise untouchability – Amazonian, androgynous, by turns transgressive and erotic. Her youth is part of the attraction, as is her attire. What’s hotter than a woman in armour? One can read echoes of her in Paco Rabanne’s 1960s space-age soldiers and Thierry Mugler’s 1990s metal femme-bots. In the last thirty years or so, she has been referenced frequently in catwalks and editorials. In 1994, Jean-Paul Gaultier placed her in embellished armour and peasant-style corseting. In 1998 Alexander McQueen paid eerie homage in a collection titled ‘Joan’. In 2006, John Galliano softened her hard edges, a half-shell of gold lashed over sweeping couture drapery. In 2018 she was crystallised in the image of Zendaya at the Catholicism-themed Met Gala, shimmering in silver Versace.

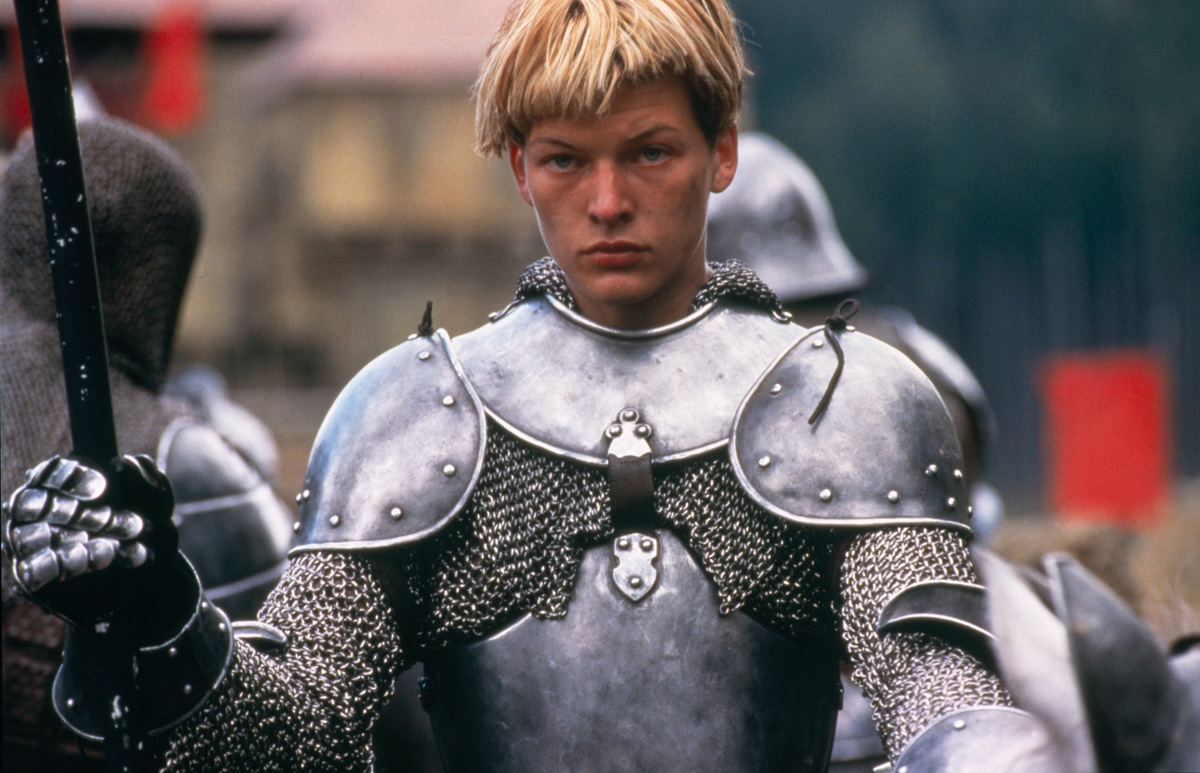

To designers and photographers, Joan has become both warrior queen and victim of patriarchy – the indomitable woman in armour who was punished for it (though you’ll rarely get acknowledgment of Joan wearing such clothes not just for reasons of comfort or pragmatism or even preference, but for the ever-present threat of sexual violence). Often, she is more archetype than actual person, joining the hallowed ranks of famous heroines and stock characters, real and imagined, who frequently hover above the catwalk as muse: Elizabeth I, Alice in Wonderland, Princess Di, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. In a 1988 advert for Benetton, Joan appeared alongside fellow tragic icon Marilyn Monroe. Embodied by high fashion models, she also tends to be very beautiful in these contexts, lingering on the feminine side of androgyny. In this respect she takes her cues from a visual lineage stretching from sultry Pre-Raphaelite paintings to the many actors, including Ingrid Bergman, Jean Seberg and Milla Jovovich, who have played her on screen, giving rousing speeches as they ride into battle and face down the male authorities that will ultimately kill them.

Balenciaga first cited Joan in 2021, conjuring a futurist medieval aesthetic in the form of armoured boots with spike heels (also worn by Douglas in the brand’s video game presentation – a fitting match, given her striking features and recurring presence in Douglas’s partner Anne Imhof’s confrontational performance pieces which mingle nihilism with mythology). Demna described his version of Joan as a ‘modern-day pacifist warrior’. Earlier this year, Turkish designer Dilara Fındıkoğlu invoked her in a poised show referencing women’s political struggle in the face of state-sanctioned violence, particularly in light of the death of Mahsa Amini last September in Iran. Fındıkoğlu’s offering was a deadly garment armoured in cutlery, titled ‘Joan’s Knives’. ‘She’s taken back her body’, the designer explained. ‘She’s coming back for revenge.’

Fındıkoğlu’s gown felt like a direct line to that Alexander McQueen 1998 collection. It remains the best and most unsettling interpretation of the saint, featuring models in chainmail and ecclesiastical-inspired pieces with blood-red contact lenses. The finale revealed a solitary figure in a ring of fire, her red bugle bead skirt mirroring the conflagration. For McQueen, Joan was a figure of fascination not just for her charisma or masculine garb, but for her conviction. Backstage after the show he observed dryly, ‘Even if I die by my cause, I’ve gone down doing what I believe in’. Elsewhere, he riffed on Joan’s long-established appeal to the gay community: ‘Anyone can be a martyr for their cause. Maybe I was a martyr for homosexuality when I was six’.

In Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism (1981), academic Marina Warner observes that over the centuries the image of Joan has become a cypher ‘instantly present in the mind’s eye: a boyish stance, cropped hair, medievalized clothes, armour, an air of spiritual exaltation mixed with physical courage’. Warner’s central argument is that each era and cultural movement has reshaped Joan to its own ends, taking from her what they need. Although she is a real historical figure, she is also ‘the protagonist of a famous story in the timeless dimension of myth, and the way that story has come to be told tells yet another story’. Joan has been adopted by everyone from feminists to far-right nationalists, cast as a patriot, mystic, holy virgin, witch and plenty more. She has been reread and reclaimed in line with our understanding of sexuality and gender. In her 1936 biography, Vita Sackville-West implied she might have been a lesbian. A production at The Globe theatre in London last year imagined Joan as nonbinary.

Fashion tends to take the courage and clothes and ditch the divine. Religious visions and voices are harder to do anything with sartorially, given that they require a relatively complex engagement with questions either of theology and mysticism, or madness. Martyrdom is also tricky, but its appealing to fleetingly allude to in a time where public discourse is dominated by debates about witch hunts, cancellations and black-and-white morality. McQueen’s response (and, in its echoes, Fındıkoğlu’s) stands out not just for its depth but its bleakness. It’s easy to say you’re referencing a martyr. Send out a model with cropped hair and chainmail, and Joan rises immediately in the imagination. For Blumarine, who showed a Joan of Arc-themed collection this spring, the association went as far as a clinging silver jersey. It’s more audacious to suggest you have some affinity with the belief, the marginalisation, the fanaticism, the vulnerability that martyrdom requires – and even harder to pull that off without rendering it trite or in poor taste.

This is the ultimate difficulty faced by any historic figure taken up by the fashion industry. The nature of the fashion show is that it requires narrative anchors – a jumping-off point, a ‘muse’, a set of visual and historic cues. In a realm that’s ultimately devoted to making and selling clothes, is it not inevitable that such figures will be rendered hollow and cliché – reduced to mere surface? McQueen proved that there is another way; others have followed, while there will inevitably be more to come in the future. In these apparitions of Joan, they are not so much shedding further light as leaning into the darkness.

Rosalind Jana is a writer based in London. She covers art, fashion and culture for publications including Vogue, the BBC, Prospect, Apollo and The Guardian