How one of Bangladesh’s best-known Indigenous artists fuses politics, childhood memories and personal anecdotes to make powerful and provocative works

In April 2014, I invited Joydeb Roaja, along with a few other artists, to perform at Pathshala South Asian Media Institute in Dhaka, where artist Mahbubur Rahman, activist Taslima Akhter, I and a few other researchers had cocurated a group exhibition titled 1134 Lives Not Numbers. The exhibition marked the first anniversary of the collapse of the Rana Plaza, a building northwest of the Bangladesh capital that housed five garment factories. More than a thousand workers lost their lives.

Joydeb was born in 1973 in a remote village in the Khagrachhari Hill District, one of the three mountainous districts in the south-east corner of Bangladesh. He belongs to the Tripura community and currently lives in Chittagong in southeast Bangladesh, bordering India and Myanmar. Because of that, we did not meet often, but I had seen Joydeb perform here and there. He is one of the few artists from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) and the Indigenous community in Bangladesh more generally who has gained visibility in the mainstream art scene, aside from artist Kanak Chanpa Chakma.

My awareness of the politics of the CHT (where there have been several conflicts in relation to land rights and autonomy), the oppression of Indigenous peoples by military forces and the reinforcement of Bengali nationalistic identity comes through the work of photojournalist Shahidul Alam, anthropologist Rahnuma Ahmed and writers Saydia Gulrukh and Hana Shams Ahmed. Shahidul worked on a project focused on Kalpana Chakma that lasted several years and resulted in three exhibitions (2013–15), repeatedly asking the simple yet haunting question: where is Kalpana Chakma? Kalpana, a young leader of the Hill Women’s Federation who had been a vocal critic of the Bangladesh army’s harassment of local Indigenous peoples, was abducted at gunpoint from her home by military personnel and civilian law-enforcement on 12 June 1996. Twenty-nine years later, she remains missing.

It is in this context that Joydeb grew up: in the hostile environment of the CHT under military rule and the conflict with Bengali settlers, experiencing humiliation, fear and anger. The overarching portrayal of the region is often its scenic beauty – mountains, forests and rivers. But Joydeb is one of the few artists who has broken that paradigm, bringing politics and personal anecdotes from his childhood into his performances and drawings.

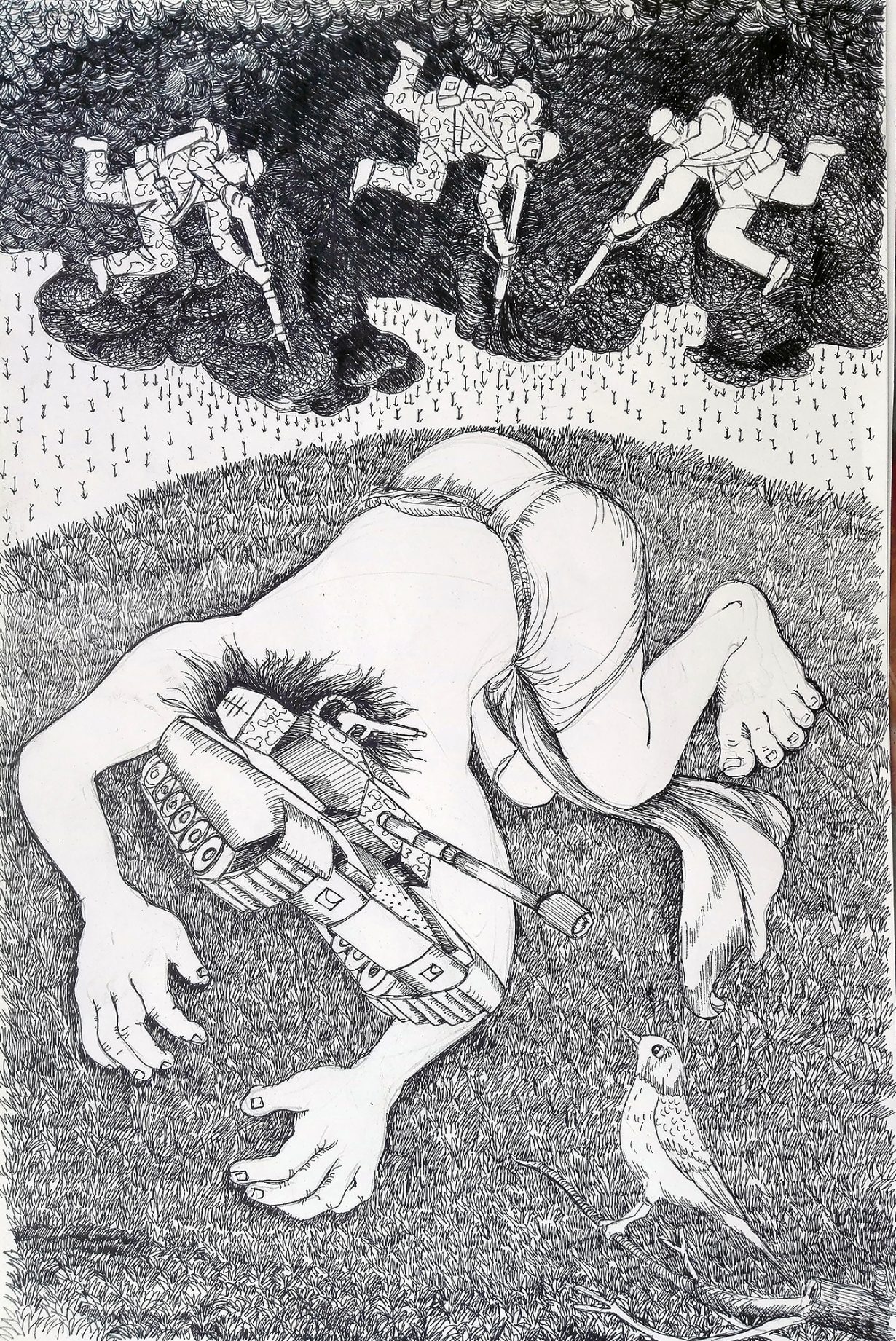

In his series Generation Wish Yielding Trees and Atomic Tree (2008–), Joydeb depicts military tanks embedded within Pahari figures (the Pahari are a minority group within the CHT), surrounded by numerous armed men. In the work, Joydeb addresses how members of the younger generation in the CHT are caught in the conflict and tension between local political parties and the brutal force of military presence. From childhood, they are unable to cultivate themselves or engage their perspectives through art, literature and other forms of education. According to Joydeb, “The new generation always carries a heavy weapon on their heads, which is destroying their tender sensibilities.” He has also performed with his daughter, balancing a cardboard tank on his head. In the photographs of various iterations of the performance they mostly appear to be strolling through the landscape, with the occasional subtle smile crossing their faces as they wander along the seashore. At times their heads seem to be in confrontation with each other. When discussing this series with me, he said that he first saw a military tank when he was in the ninth grade, and since then the image has never left his mind.

I asked Joydeb whether the performance or the drawing came first. He smiled and said, “I love doing these performances because they don’t cost much. They are spontaneous – I can use my body to react to my time.” Sometimes he sketches in relation to performances (either before or after they take place), producing works that later evolve into largescale drawings. For me it was fascinating to observe how fluidly Joydeb’s body moves between performance and ink on paper. And how his drawings play with a politics of scale: the Pahari figures are much larger than all the members of the armed forces.

Like many young artists across South Asia, Joydeb initially struggled to generate an income from his work. He recalls being in awe of Water is Innocent!, a 2004 exhibition by the pioneering artist Dhali Al Mamoon, who was also a professor at Chittagong Art College. While Joydeb admired the scale of the older artist’s installations (which depict how the construction of the Kaptai Dam, to generate hydroelectric power for the larger Bangladeshi state, caused the flooding of local communities and the displacement of their inhabitants), he feared he would never be able to afford to make such elaborate work. Joydeb developed his own practice within artist collectives such as Porapara Space For Artists in Chittagong and Britto Arts Trust in Dhaka. However, a pivotal moment came in 2009 when he attended a workshop with Japanese poet and performance artist Seiji Shimoda. From that point on, Joydeb was drawn to performance art, realising that meaningful artistic expression does not require grand arrangements; instead, gestures, movements and sonic experiments became his primary materials. His body became an act of resistance, a daily form of expression within and against an increasingly capital-driven art market. Recently, Joydeb built a studio in Rangamati, in the cht, on the same land where the house of the Chakma king (the Chakma people are the second largest ethnic group in the CHT) was washed away due to the construction of the Kaptai Dam. He visits the studio on Thursday evenings, as his daughter’s school is closed on Fridays and Saturdays.

Joydeb and his friends grew up cultivating rice using jum (slash-and-burn) farming. His figure drawings are filled with intricate details, reflecting the region’s textile-weaving and craft traditions. These textures resemble veins, flowing through bodies and landscapes, representing generational experiences transmitted through practice and oral history. One recurring element in Joydeb’s work is his connection to childhood memories – cultivating, cooking, wandering down narrow creeks in the mountains and exploring the flora and fauna. I have often observed his images on Facebook, where he is captured cooking in the middle of a water source, trekking and performing spontaneously, sometimes with only nature as his audience.

On 25 November 2024, Joydeb wrote a Facebook status update:

––I have not drawn a picture since November of last year! I have been in the studio since the day before yesterday. I wake up at four o’clock every morning, but I still haven’t been able to draw anything. I spent two days thinking about what to draw, why to draw. But in these two days, I have been taking care of the garden, sweeping the studio, watering the trees. If the unemployed artist does not concentrate on his work, then it is difficult to survive. Hope Mother Nature will give me some guidance. Waiting for that auspicious day.––

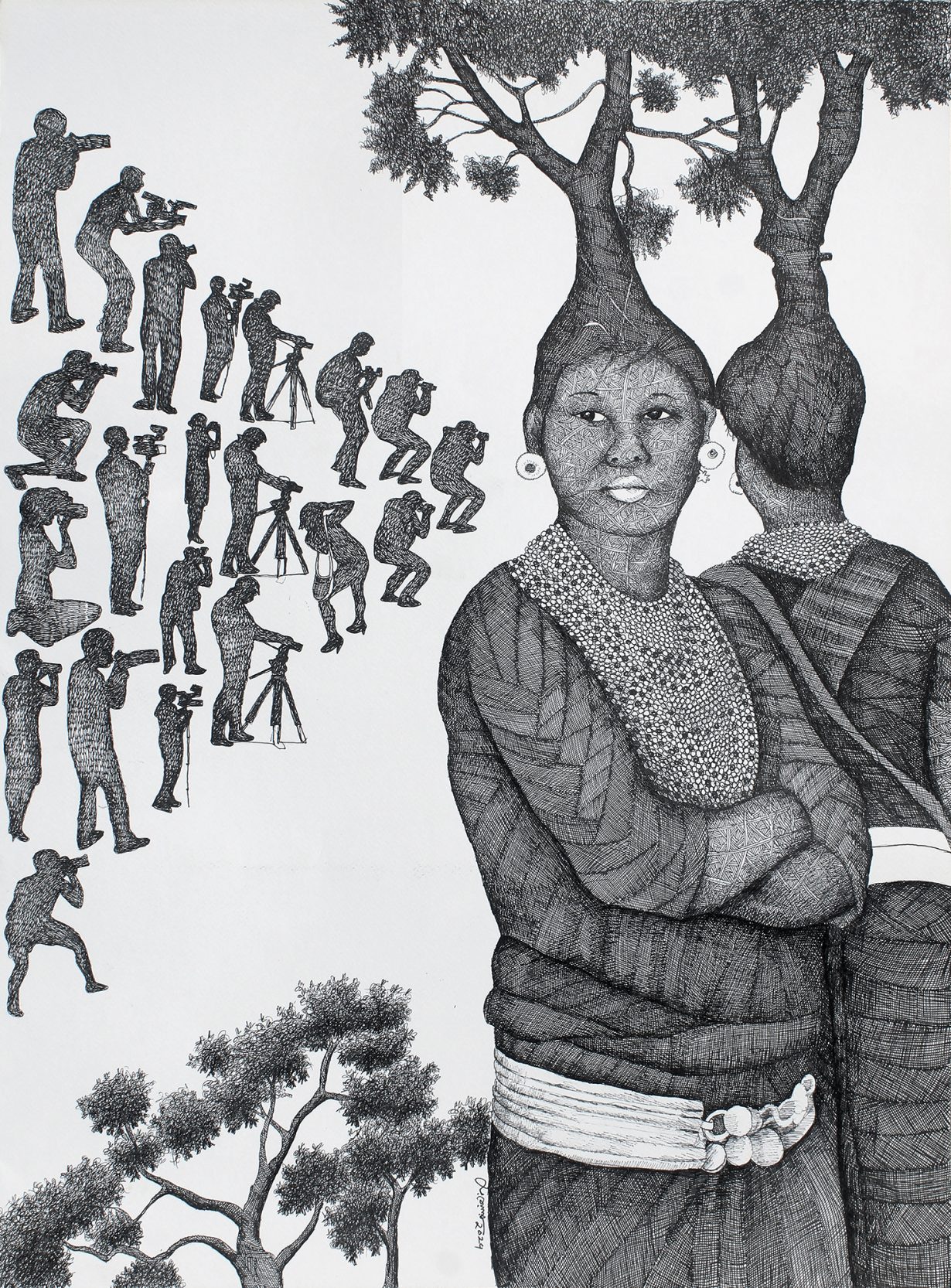

Joydeb’s recent series The Future of Indigenous Peoples (2024) is on show as part of the Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane. It highlights how Indigenous bodies are constantly surrounded – by photographers, journalists, media spectators, surveillance drones and helicopters. And how these violent interventions disrupt traditional rituals and performances. Research indicates that the ratio of Bengalis to Paharis in the CHT has reached nearly 1:1. Joydeb speculates that one day Paharis will become a rare, almost invisible species. He recalls in 1982, when he used to go to local markets, he would see 90 percent Paharis and 10 percent Bengalis from the flatlands.

As violent ethnographic research continues to categorise people into increasingly rigid identities, Joydeb’s drawings and performances resist these frameworks. His work presents a much more complex and layered understanding of the larger region – one that challenges colonial cartographic and ethnographic perspectives on who we are as Bangladeshis today.

Work by Joydeb Roasha can be seen in the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial, Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, through 27 April

Munem Wasif is a Dhaka-based artist working in photography

and moving image. An exhibition of his work, Kromosho,

is on view at the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts, Dhaka, 18 April – 29 May

From the Spring 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy