Looking back on the artist’s life’s work which has come to draw from Buddhism, quantum mechanics, environmentalism and Asian arts & crafts

Writing in 1997, Uthit Atimana, then director of Chiang Mai University Art Museum, had this to say about Kamin Lertchaiprasert after the latter had returned home following studies at the Art Students League of New York during the early 1990s: ‘It seemed that Kamin had thrown away the kind of art that conveyed the energy of emotions, and he started to emphasise conceptual-based art works, inspired by his readings and his rationality. In this kind of art, the concept comes before the emotions. [But] Kamin still held on to his everlasting characteristic, namely “directness”.’

It’s a narrative that is still writ large at the Chiang Mai-based artist’s own rustic gallery – the public-facing ‘office’ of what Lertchaiprasert calls his ‘31st Century Museum of Contemporary Spirit’. Lining the raw concrete walls of this high-ceilinged exhibition space is a series of monochrome, mixed-media self-portraits created between 1983 and 1986, before New York, while he studied printmaking at the Thai capital’s foremost art school, Silpakorn University: it’s art that conveys the energy of emotions. In simple pen drawings rendered in wild, violent lines on damaged canvases, for example, his brooding expression – directed out towards the viewer – is pitched somewhere between self-loathing and cry for help. The artist, in this post-adolescent phase, appears to be wallowing in a world of hurt. Or as the greying fifty-nine-year-old Lertchaiprasert now clarifies: “I blamed myself for my mother’s sudden death in 1983.”

Also unmistakeable during a visit to his 31st Century Museum is a sense of what came later: an artist who, after reading books such as The Tao of Physics (Fritjof Capra’s 1975 exploration of parallels between modern physics and Eastern mysticism) while studying and working in New York, developed an intense interest in Buddhism. And who, upon moving back to Thailand in 1993, concocted a forthright practice that duly expanded upon that intense interest – and remains in motion today. Thirty years on, his earnestly conceived conceptual art projects still effusively crosspollinate strains of potted Buddhist thought with inspirations drawn from across time and space (quantum mechanics, environmentalism, Asian arts and crafts, chance encounters among them).

Courtesy the artist

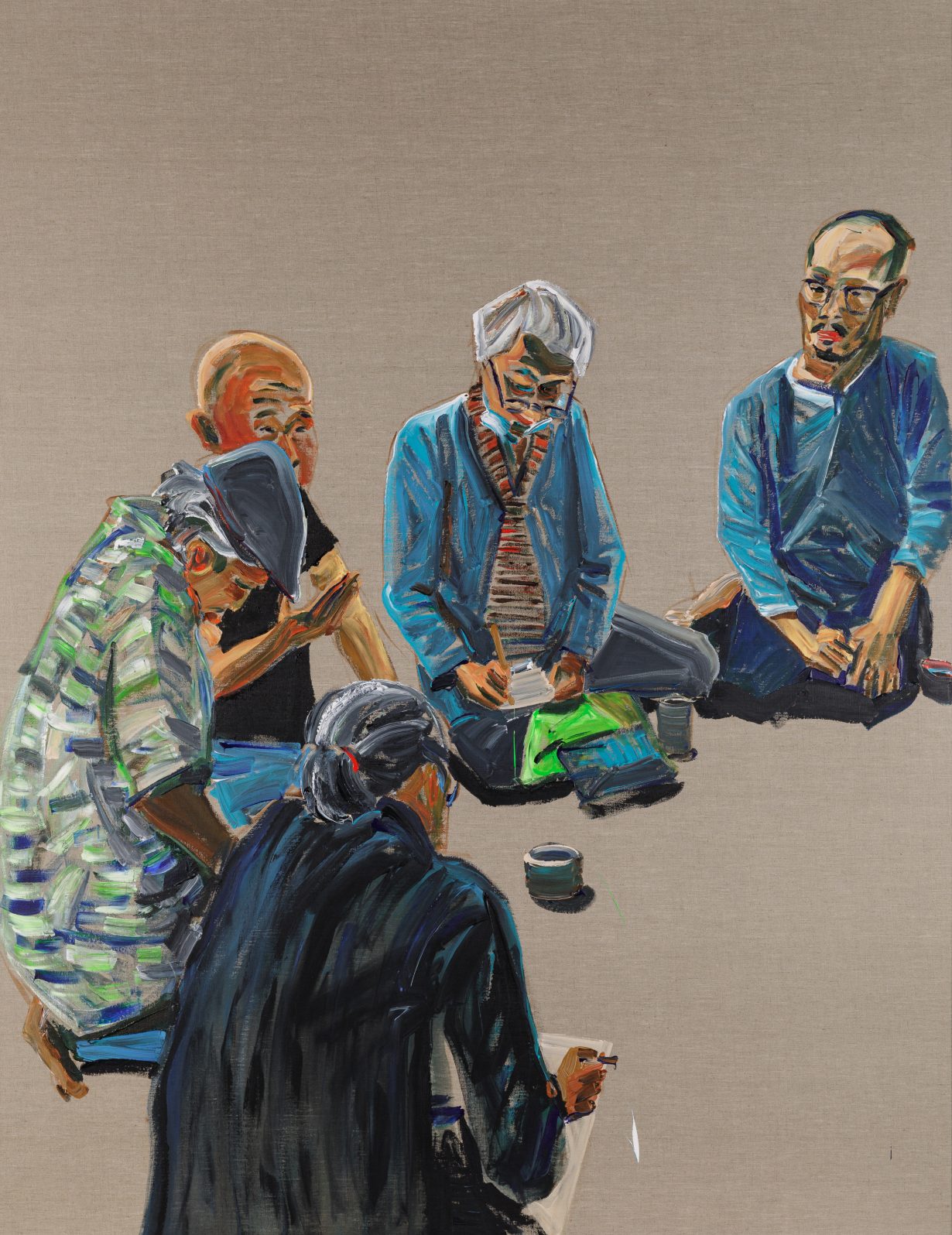

A collaborative videowork in dialogue with Lertchaiprasert’s early self-portraits signposts this approach. In Humanimal (2023), a 40-minute therapy session shot at the museum, Thai performance artist and trained psychotherapist Dujdao Vadhanapakorn attempts, through the fielding of various question-and-answer exercises from behind the camera, to peel away the layers of Lertchaiprasert’s psyche. To show just how far he has come, personally and artistically. “What incident in your teenage years do you think about a lot?” she says at one point. “I didn’t understand love. I was selfish,” he replies without flinching. At another juncture, she asks: “At present, if you’re depressed, who is the one you need?” His poised response betrays the calming benefits of an introspective practice that has long sought to blur the line between meditation and markmaking: “Emptiness. Sitting here now. Being in the present moment.”

Internationally Lertchaiprasert has long been associated with fellow artist Rirkrit Tiravanija and the pair’s The Land Foundation: a communally run art-farm project in rural Chiang Mai that, after they cofounded it during the late 1990s, quickly became known as an exciting theatre of what curator Nicolas Bourriaud had then recently christened ‘relational aesthetics’. But this designation is, while not totally spurious, something of a misnomer. For years, The Land’s structures have been crumbling due to a lack of investment and care (each artist-funded structure is that artist’s responsibility), and while Lertchaiprasert and Tiravanija remain close – they are neighbours, in fact – the former is now merely an adviser to their once shared project. Philosophically, he stresses, The Land remains compatible with his outlook – “It’s a spirit house. It does nothing but it does everything,” he says when I ask what function it now serves – but these days his process-led art owes more to the ascetic quests and private rites of Zen and Tibetan Buddhism than it does the flawed non-ownership principles of a heavily fictionalised utopia.

Rightfully, he is better known for gamely embarking on ritualistic art exercises of a drawn-out, disciplined and mono-maniacal nature. Centred on the discovery of his internal nature or widely applicable philosophical truths, these ruminative yet action-oriented quests commenced with installation projects such as Problem-Wisdom (1993–95), which comprises 366 papier-mâché figurines and objects, each representing both a societal problem and a spiritually informed solution. To bring a state of balance – between good and bad, right and wrong – into being, Lertchaiprasert inscribed idiomatic phrases inspired by Buddhist and Taoist thought onto birds, frogs and noses, among countless other whimsical hand-sized sculptures made from pulped Thai newspapers.

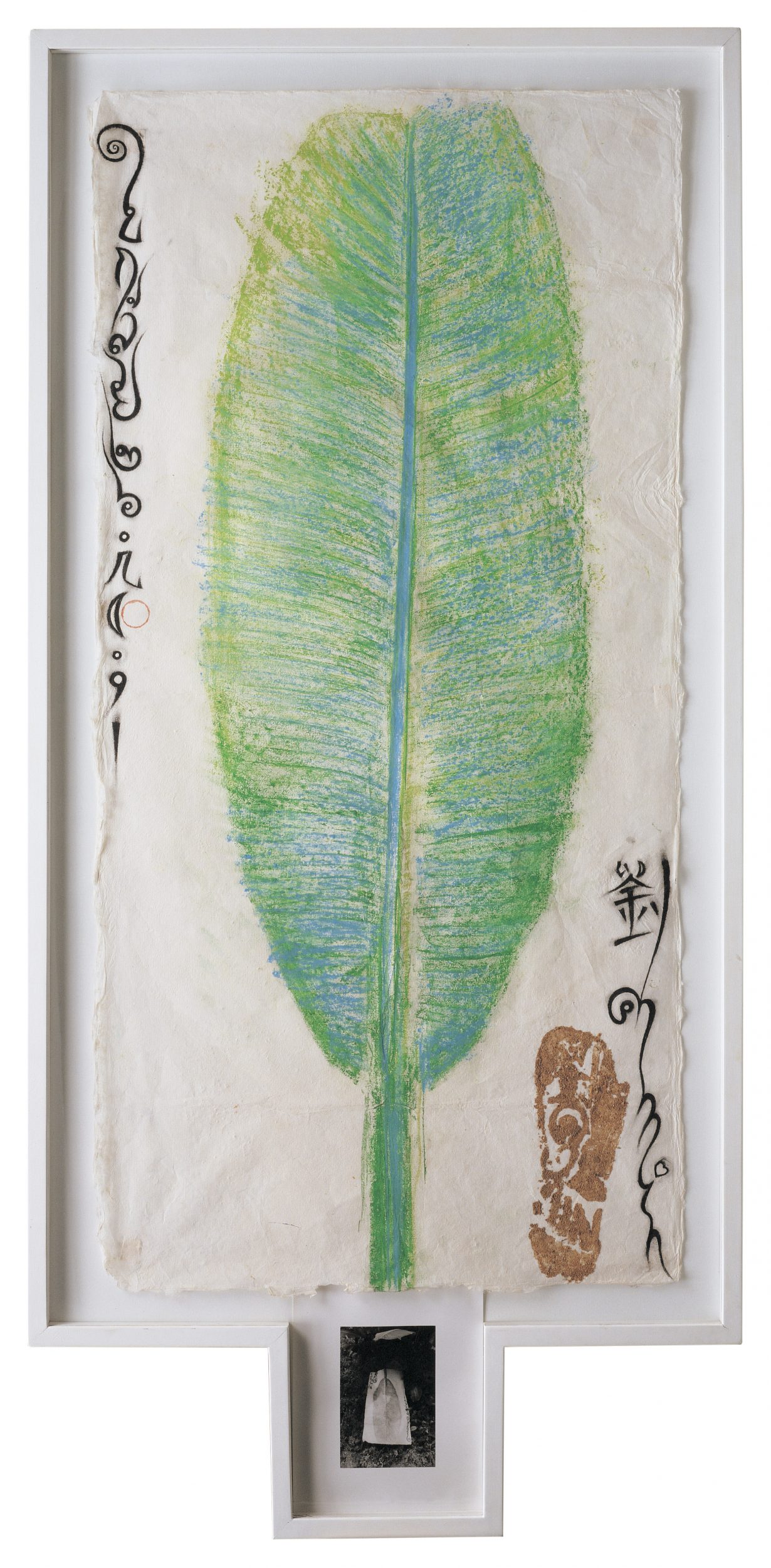

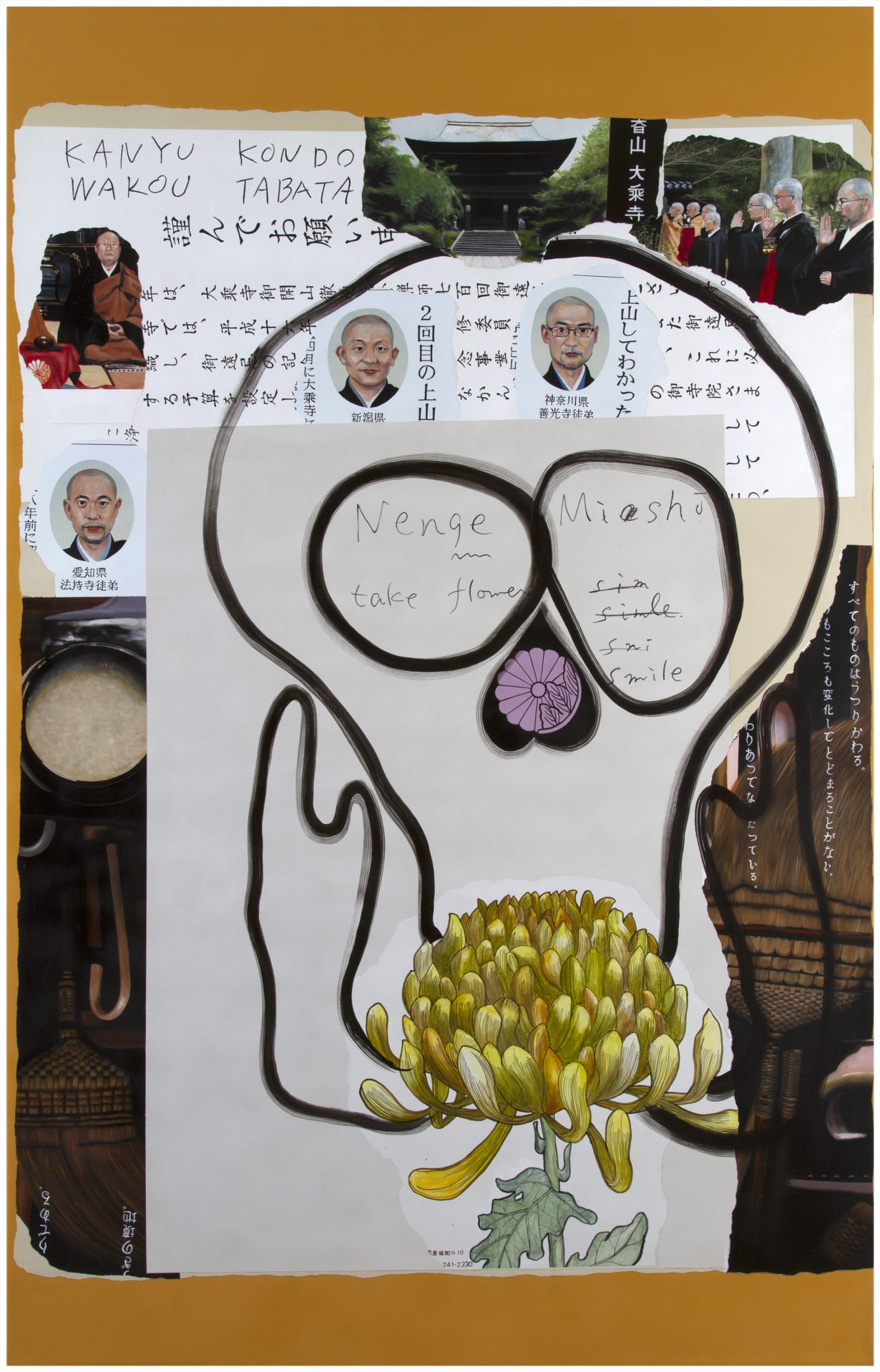

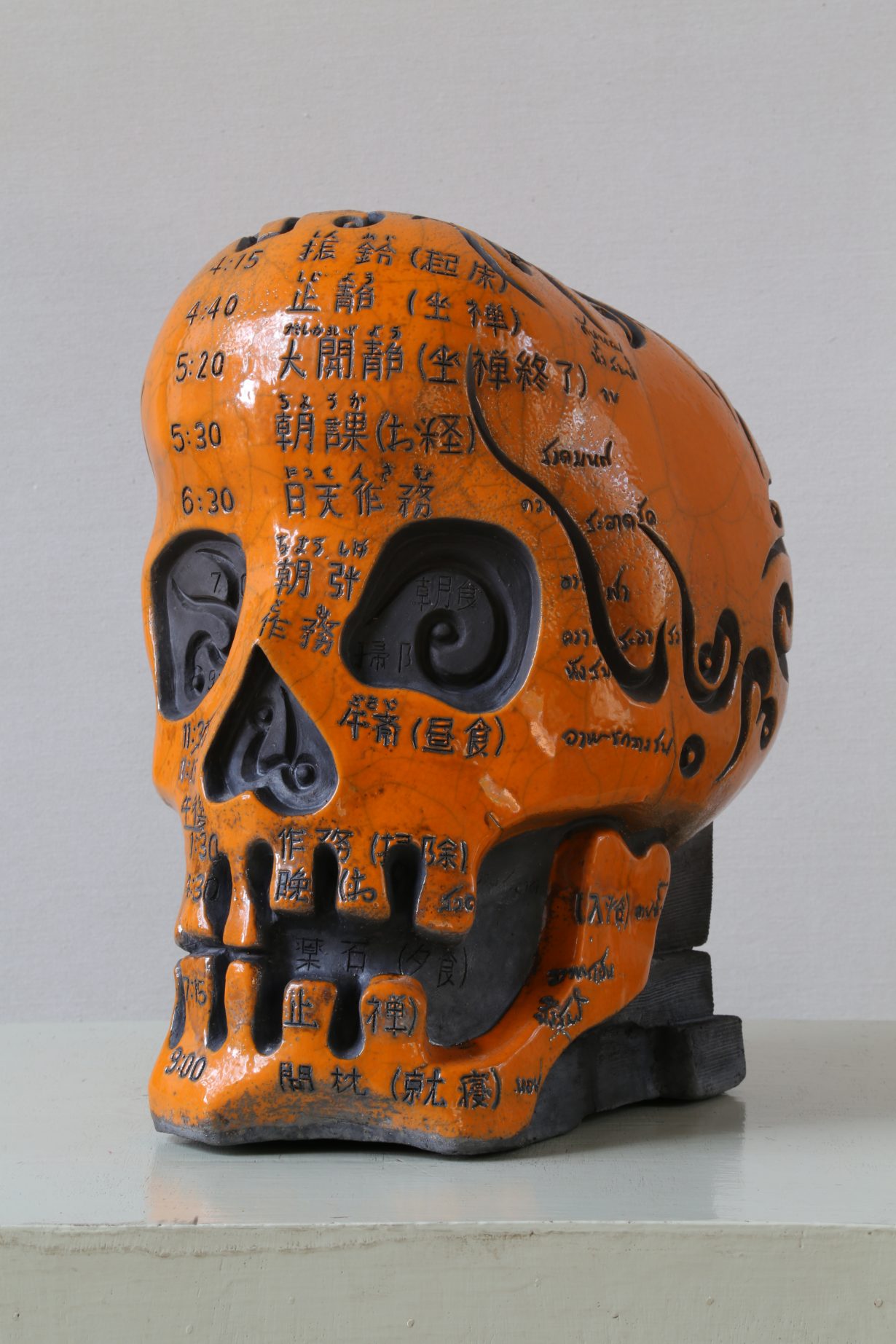

The frequency and intensity of such projects has barely let up since. Between 2008 and 2011, for example, he set aside time each day to make an A4-sized mixed-media collage out of old receipts, letters, tickets and flyers. The project, titled Before Birth – After Death, culminated in a wall of 715 collages, each one bearing the contours of a skull as well as baroque, snaking Thai handwriting relaying aphoristic observations gleaned from meditation. In the years since then he has handmade 365 raku tea bowls (Nothing Special, 2014–15), produced a suite of calligraphic, expressionist paintings (Drawing Series – Symbolic of Emptiness, 2015–18) and painted 90 portraits of inspirational people (scientist David Bohm, Hindu mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, kind-hearted mechanics, etc), each with a related anecdote scrawled on the canvas’s verso (Pure Perception, 2021–22).

Indeed Lertchaiprasert goes on to explain that the old self-portraits and new videoworks currently on show are in fact components of his latest elongated quest. Launched last August, this durational endeavour is set to unfold at his ‘office’, through rotating exhibitions of around three to four months each, over a five-year period.

In one sense, this Self-Enquiry Project, as he calls it, is an attempt to reconcile his younger selves with his current self: to see what the former can teach the latter, and how the latter can rethink the former. Plans are fluid but each chapter will, with the help of collaborators from different backgrounds, revisit artworks from across his career. Next up, for example, is Aesthetics of Awkwardness, an exhibition showcasing works from 1991: brash, text-based canvases that poked fun at the clannishness and conservativism of Thailand’s national exhibition system and, in so doing, rattled many an ajahn (professor).

In another sense, Self-Enquiry Project is just the latest iteration of his longstanding attempt to dissolve his spiritual practice into his artistic practice. To try and achieve this, he recently pivoted to a medium he has never tried before: landscape painting. Twice a week, typically at dusk on Tuesday and Friday, he takes the 15-minute drive to his thatched open-air studio on the outskirts of Chiang Mai. After settling down in this raised wooden hut, he then paints the setting sun, racing against time to render the distant hills as swirling brushstrokes and impasto blobs. Finally, he completes the work by scrawling a haikuesque poem in Thai on the reverse. The latest reads: ‘Man-made is not fog / Sun sets before time / The golden cloud drifts’. He plans to do this for five years. Or until he feels disinclined to paint any longer. “Sometimes you learn something and then you know you cannot keep going. But for now, I don’t know, so I continue,” he says.

As self-indulgent as all this may sound to some, Lertchaiprasert insists that the Self-Enquiry Project is an undertaking of societal, as well as personal, consequence: the crucial step on his search for a “spiritual aesthetics”, an aesthetics beyond self-centric notions of the physical or mental that, he claims, “goes back to the inner mind of each person… back to the nature of mind”. This search, he adds, will culminate with both an exhibition of the completed landscape paintings and a book: an atlas of sorts mapping out his lifelong discoveries concerning society, nature and the contemporary spirit.

Hearing him lay out the teleological components and goals of this late-career gauntlet – as he does willingly for many visitors – is enough to leave you with an unshakeable sense of that everlasting characteristic: directness. This trait, I believe, is both a bane and a boon. Directness has, as Atimana Uthit also wrote back in 1997, sometimes made Lertchaiprasert appear ‘sarcastic and jeering’ or ‘dictatorial in discussions’. His directness also leads his broad-brush philosophising to occupy a more central role in his practice than it arguably should. In interviews and wall texts, he often comes across as more proselytiser or mystic than artist, verbose and unduly theoretical.

But directness also endows him with the capacity to field existential questions using a striking economy of means: humble materials, diverse but intersecting philosophical strands, a laissez-faire attitude to time. And Lertchaiprasert’s directness sustains a rare sociability – an unbroken feedback loop of sincere, pure expression and sincere, pure communication with himself and anyone who’ll listen.

“The first wisdom I’m seeking is for myself. But when I feel I understand somehow, I want to recheck myself and share my knowledge,” he tells me. “That is my vision for my whole practice.” After taking in the current exhibition, many visitors join him upstairs in a tea zone modelled on the wabi-cha principles of Japanese tea master Sen no Rikyū (1522–91), then scribble messages in a dramatically spotlit guestbook. ‘I hope you will find what you are looking for on this wonderful and in a sense desperate journey,’ reads one heartfelt remark.

Writing in the catalogue for Pure Perception (a series that was exhibited across three Bangkok spaces, including ATTA Gallery and Numthong Art Space, in 2022), Zara Stanhope posits that Lertchaiprasert’s art ‘holds a vision of goodness for a society at an interregnum’. This vision is, admittedly, easy to mock. Given all the planetary crises we face and the lack of clarity about the future, what good is a platform that, as he puts it, “offers people a mirror to see themselves”? Are Kintsugi bowls that serve as a metaphor for human faults and frailty, paintings of daily life and gnomic titbits gleaned from the scriptures of long dead priests, enough to see us right?

His retort to such criticisms could, if he was inclined to retort, be Art for Air. In Chiang Mai, the city he moved from Bangkok to in 1996, there is no greater emergency than the air pollution, caused by crop burning and other factors, that blights the north between January and April (if not longer) each year. In early 2021, Lertchaiprasert responded by rallying his artist friends, hosting an auction to raise money, then pouring the proceeds into a citywide exhibition, staged across galleries and public spaces, to raise awareness. Today, Art for Air continues, despite funds almost running dry. At the Bangkok Art Biennale 2022, a display of works from the 2021 edition was joined by an educational videowork, directed and scripted by Lertchaiprasert. In it, an avatar of an elderly Greta Thunberg tells a precocious baby elephant that humanity’s “meta-awareness” and “inherent compassion” could, if properly channelled, further the clean air movement (Bangkok is floating, no garbage, 2022).

In a sense, this Buddhism-inflected environmental activism seems far removed from his enlightenment seeking: the former aims to alter destiny; the latter promotes dispassionate acceptance of it. Yet Lertchaiprasert insists there is no paradox. “Life is transformation, but it doesn’t mean you have to die now,” he says matter-of-factly.

Art for Air 2 runs through October at art venues across Chiang Mai and Bangkok

Self-Enquiry Project’s third exhibition, No Reference Conditions, is on view through 30 May at the office of the 31st Century Museum of Contemporary Spirit, 100/6 Moo 10 Soi Wat Umong, Chiang Mai