Koo Jeong A’s project for the Korean Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale seeks to explode the idea of nations and divisions altogether

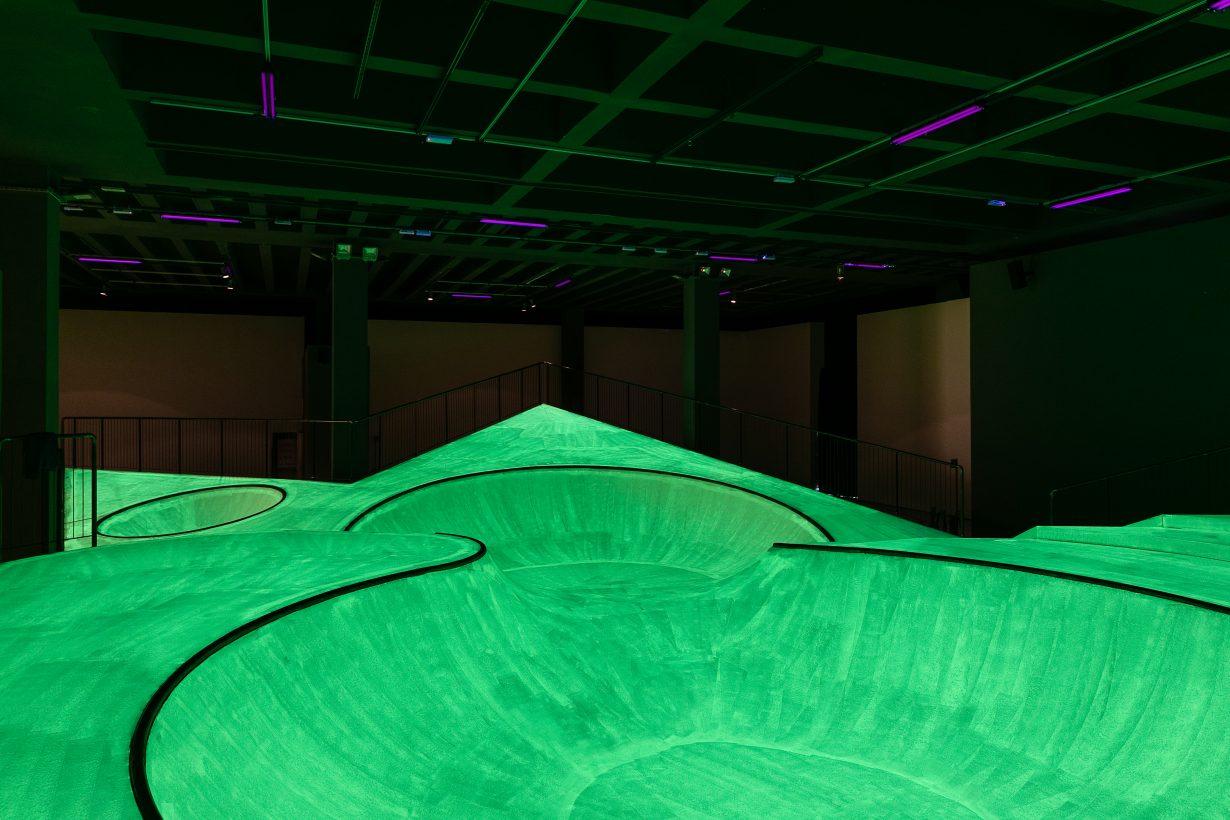

Koo Jeong A brings an immaterial dimension to the Korean Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, in an exhibition that probes the cognitive correlations between scent and memory. This project encapsulates the artist’s conceptual approach to activating altered states of perception, which yields site-specific installations that explore preexisting notions of presence and absence, real and unreal. Throughout Koo Jeong A’s three-decade-long career, this methodology has taken shape in the form of skateparks slathered in phosphorescent paint, AR ice sculptures viewable only on digital-device screens, organic matter that emits sonic vibrations and other interdisciplinary manifestations of uncanny imaginaries. Regardless of the medium or context, Koo Jeong A always invokes poetic reassessments of the mundane by making felt that which exists beyond the spectrum of everyday perception.

For their commission at the Korean Pavilion, Koo Jeong A presents a body of work that expands on their longstanding interest in ephemerality. ODORAMA CITIES proposes an invisible portrait of the Korean Peninsula – a ‘scent landscape’ that renders individual memories as olfactory sensations. During an open call asking, ‘What is your scent memory of Korea?’ the artist collected some 600 individual stories, then collaborated with Seoul-based perfumer nonfiction to transform these memories into an assortment of fragrances that visitors encounter within the Korean Pavilion in Venice. ArtReview spoke with the artist about their enduring interest in our sense of smell and its capacity to conjure pluralistic constructions of national identity.

ArtReview Your project for the Korean Pavilion involved a huge number of people who contributed to its development. How did ODORAMA CITIES come about and what was the motivation for undertaking such a complex project?

Koo Jeong A I truly wanted to talk about an expanded and inclusive concept of the nation, which we collected in the form of scent stories through an open call. It started with a question about scent memories of Korea from all over the globe – not only limited to Koreans but also non-Koreans, as well as people who came to Korea or spent time there for work, or who were adopted or currently live outside of Korea but still have a story to tell about the scent of Korea, from very long ago to the recent past. We received 600 submissions from June to September last year. So ODORAMA CITIES is certainly about collective thinking as well as remote imagination, something that is very abstract and at the same time becomes a wider story about creating a kind of new knowledge or meaning.

AR Scent has been an area of interest for you since the very beginning of your career. It’s interesting that scent is capable of conjuring very visceral responses – which typically correlate to some sort of memory of a place, person or emotion – yet these memories are unique to each person. This makes scent a universal medium that also has a very personal dimension. In your numerous olfactory projects from throughout the past three decades, how do you typically go about selecting the scents that serve as the integral components of these installations?

KJA My first exhibition with scent was in 1996, when I was living in a very small studio on the top of a building in the centre of Paris. I decided to move out, and so I had three days of free space in my little studio and wanted to celebrate that shift of moving to a slightly bigger studio. I didn’t produce anything like a special scent, but I bought mothballs from a nearby shop. They had exactly the same scent as a grandmother’s cupboard.

AR That’s a very distinctive scent, and one that is recognisable across generations and cultures. Did the decision to use mothballs come from a certain memory of yours?

KJA By using mothballs, I just wanted to celebrate that vacuum of time and space, which was very important for the installation. Memory is dynamic – it is not a precise place in the brain, as [author and science historian] Israel Rosenfield told me. But my idea was to shift the vacuum space into a common area or common future, and that motivation was also a part of the idea for ODORAMA CITIES. Of course, when we collected the scent memories last summer, there were several people who wrote about the mothball smell, so we also included it among the 17 scents selected for the exhibition.

AR Whereas your previous works were all based on a single scent, visitors to ODORAMA CITIES will be experiencing a whole ‘scent landscape’. How and why did you transition from working with one scent at a time to working with a broad spectrum of scents?

KJA When I was invited to propose a project for the Korean Pavilion, I was thinking of the need to talk about our time, which is a time of separation. I think it’s important to think more about togetherness and about a common future. And since the Giardini in Venice is also divided into nations with the pavilions, with this project I wanted to provoke something that will create some transnational pavilion that proposes an alternative to this fragmented outlook. That was the first motivation. By constructing a portrait of the Korean Peninsula, it was totally possible to compose a scent landscape out of people’s immaterial knowledge. This portrayal of the Korean Peninsula doesn’t provoke any sort of division of nations, but instead unification and togetherness – not separation but working together.

AR What was your process for pulling keywords from the 600 individual scent memories collected through the open call’s many responses? And how were these keywords used to generate the actual scents that you produced for the exhibition?

KJA As we read through the 600 stories, we found lots of repetition. People wanted to remember something special to them and there were common themes, such as sharing memories of their family or their country, their experiences in nature – whatever memories make them happy. We created a database that tracked the words that were repeated, the different scents that stood out and the style of storytelling or text. Then we selected the top 50 words and I divided them into cities. We made a kind of molecule out of these modules and then we started to construct. We were looking for very structured words that represented Korea and the diversity of the country, incorporating the real dimensions of people’s experiences from all over the world.

AR This plurality of dimensions also translates into the realm of dreams, which are notoriously slippery in terms of where and when their stories take place. Memories are rooted in actual experiences in the physical world, whereas dreams are less tethered to reality. I think ODORAMA CITIES activates both paradigms. It’s based on individual scent memories, but they are injected into a space where the actual thing connected to that memory is missing. In an interview for the 2023 exhibition Odor, Immaterial Sculptures at MGK Siegen, you said that ‘smell is the layers of construction, a master plan of where you want to be’. Do you think that your project for the Korean Pavilion is also about using smell to construct dreams of the future?

KJA Totally, because the microparticles in each scent have different speeds when they move in the air. Thinking about the diversification of dimensions, I have been working in n-dimensional space, following mathematician Georg Cantor’s set theory – in dimension one and dimension two, you can’t see any differences between the triangle and the square, but in three dimensions, you can finally see their shapes are different. If you go into five, six, seven, n dimensions, you will have endless invention. The very micro-particles of scent also have all these different dimensions in chemistry, in nature and in ourselves when we share space with those particles. The scientist Carlo Rovelli said that what you see is not always real and that time doesn’t pass by – rather, time is always a combination of the events and relationships in both a fast and slow state. All the probabilities and state relationships are interconnected, so when you are in the actual exhibition space of the Korean Pavilion, an image will become a vision in your brain and you will see yourself.

ODORAMA CITIES is on view at the Korean Pavilion in the Giardini, as part of the 60th Venice Biennale, 20 April – 24 November

Andy St. Louis is a Seoul-based art critic and curator