What is it that threads together van Eyck, the Bauhaus and Mao, not just within the space where the artist works and reads, but within the context of his oeuvre?

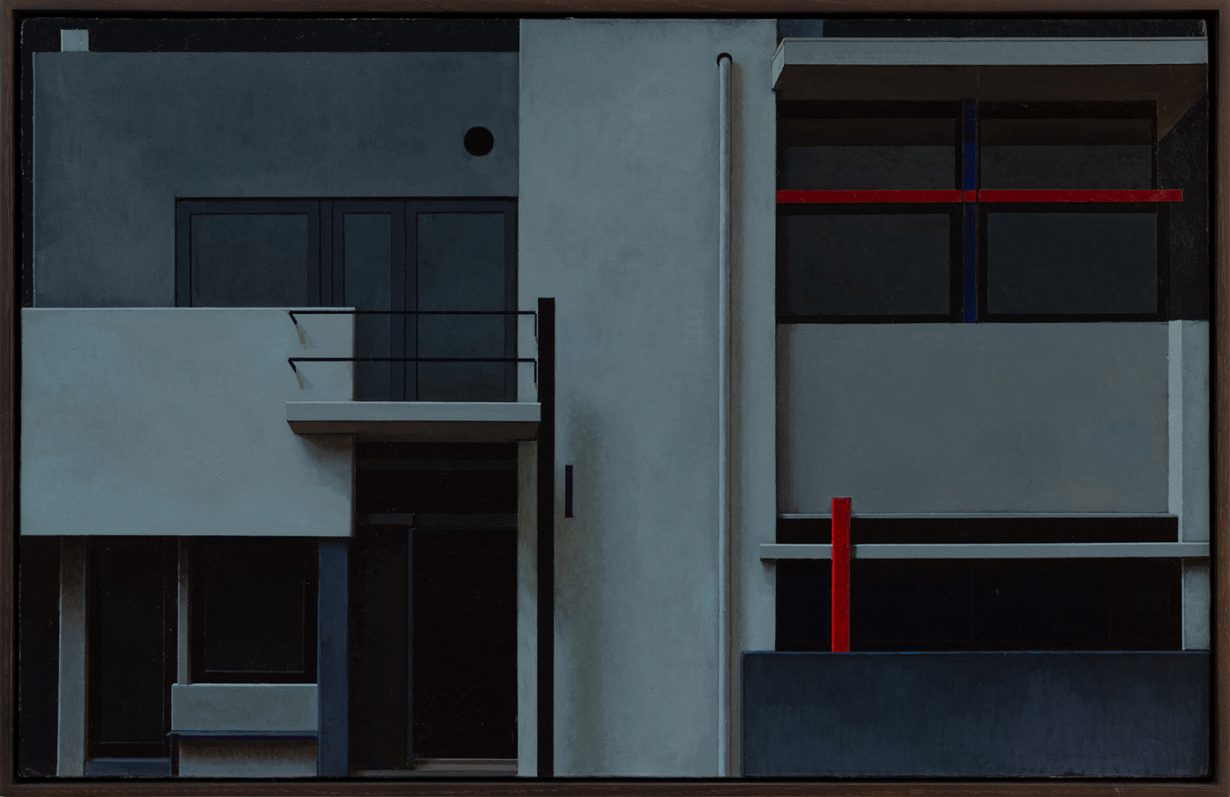

Before my visit to Liu Ye’s studio in Beijing, he messaged me to ask if I was afraid of dogs: “No one else is home so I have to take care of the little dog today”. I bet he has one of those teddy-bear-like poodles, I thought to myself. The little dog, however, turns out to be a giant white Akita-inu, who in fact looks a bit too large for Liu’s studio. Unlike the majority of painters in Beijing, who take up factory warehouses for their vast floorspace and high ceilings, Liu opted for a modern residential flat as his workplace. His studio is relatively small and kept astonishingly neat and true to its modernist decor. There are only a few paintings on the wall, all under tabloid size. One is of the facade of the Gropius-designed Bauhaus Dessau. I had seen a picture of the painting before, but only in that living room, standing next to the dog and Liu’s collection of Bauhaus chairs, did I realise how small the painting actually is.

The studio itself reveals the artist’s aesthetic inclinations: the minimal decor, midcentury modern furniture, vintage toys in trichromatic colours; fitting oddly among them is a porcelain figurine of Chairman Mao by the kitchen. Over at the dining table, Liu has been reading a catalogue of Jan van Eyck’s complete works. The Chinese artist has repeatedly returned to the Early Northern Renaissance painter for inspiration over the last three decades. He points out a painting in the catalogue that catalysed a perception shift for him, the experience of which he still remembers vividly. Liu saw his first van Eyck in person at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin during the early 1990s, prior to which he had only seen images on poorly printed artbooks back in China, which neither delivered a sense of scale nor triggered much interest on the part of the young artist. Measuring only 29 × 20 cm, Portrait of a Man (Giovanni Arnolfini?) (c. 1440) nevertheless dominated the entire room at the Gemäldegalerie, at least in the eyes of the young painter (then in his mid-twenties). And van Eyck has been one of Liu’s favourite painters ever since.

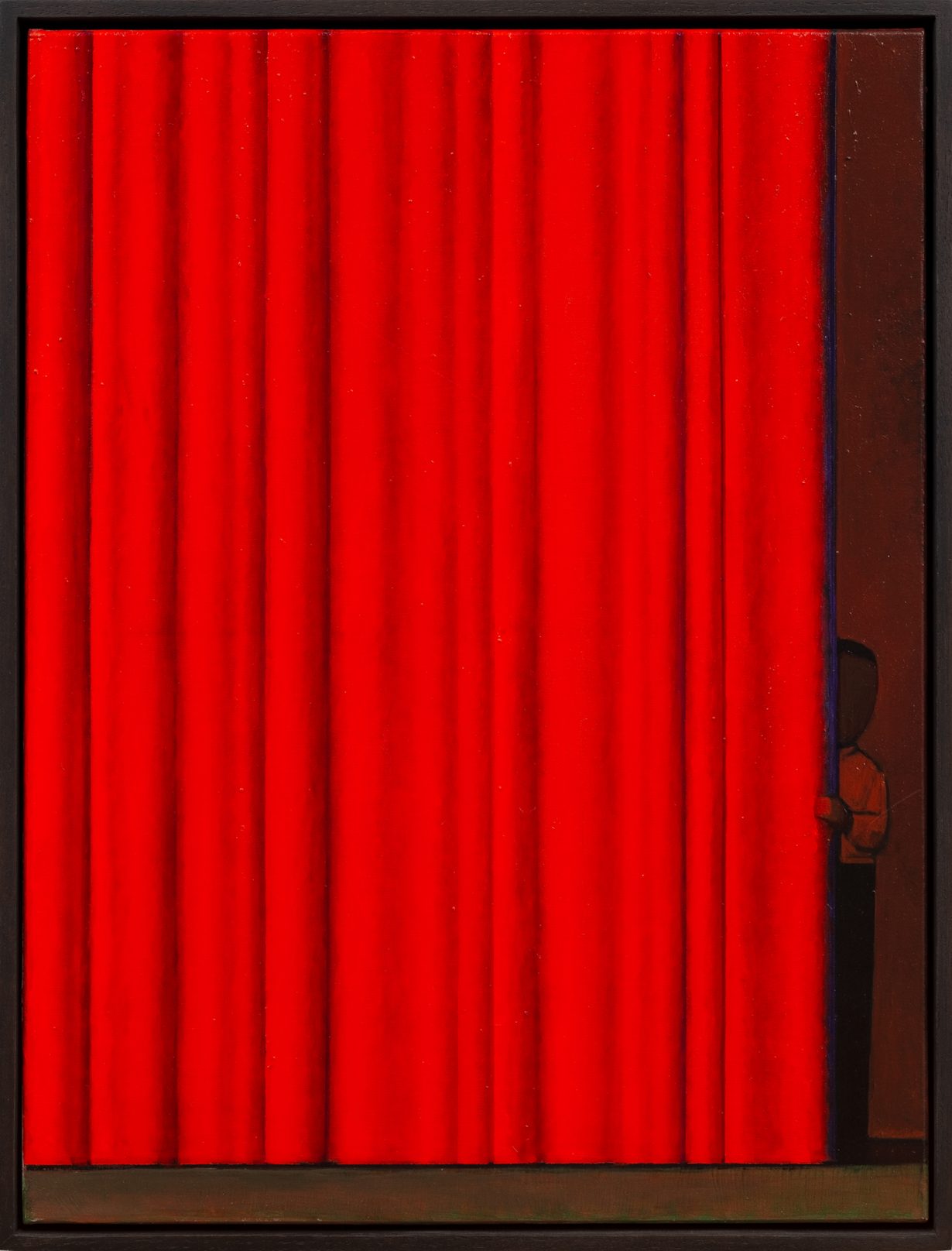

What is it that threads together van Eyck, the Bauhaus and Mao, not just within the space where the artist works and reads, but within the context of his oeuvre? Liu’s early works, from the 1990s, took a more explicit approach to combining disparate cultural elements – from his experimentation with postmodern compositions (Atelier, 1991) to the famous Baishi knew Mondrian (1996). But Liu is not so interested in a cultural reading of the subjects he had distinctively chosen to put in his paintings. Political Pop was all the rage in Chinese contemporary art when he returned to China from Germany during the mid-1990s. And critics have made direct links between Liu’s frequent deployment of the colour red and his Chinese background. But this is something the artist himself vehemently denies, along with any projection of political meaning onto his work. As far as he is concerned, he consciously steers clear of overtly political symbols within his painting. And there is something undeniably liberating in the straightforward approach: in stating that red is just red; that the red associated with Mao’s politics is essentially no different than the red associated with Mondrian’s paintings; and that a little red book is just a little red book.

It’s a way of reclaiming the universal qualities of visual language and an approach that has allowed Liu to be ever more confident about being just an artist as opposed to a Chinese artist – even in the age of COVID-19, when he cannot leave China to attend many of his exhibitions in the West. Indeed, looking at his works of recent years, one could hardly find any explicit traces of the artist’s experience in China. In keeping with that, when talking about his admiration for masters like van Eyck, Liu eschews any categorisation of East and West: as he has said in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, ‘That’s not another culture – that’s culture’. However, that’s not to say that the East/West divide – of cultures and politics – is something he doesn’t know well.

In 1989, on the recommendation of a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing, where he had studied for three years (back then, students needed official recommendations to be able to leave the country, and only a limited number of recommendations were assigned), Liu Ye arrived in Berlin with a student visa. Because he flew Aeroflot – the national airline of the Soviet Union back then – from Beijing, the plane arrived in East Berlin. Coming from a socialist country, he didn’t need a visa to enter East Germany, but no one from his school in West Berlin could travel there to pick him up. Instead, he walked a long, fenced road at the airport that connected and separated the two Berlins, little knowing that the path and the divisions in the city would soon become defunct.

Still, during his first few months in Berlin, Liu’s Chinese passport allowed him to go to East Berlin freely, a benefit most of his classmates in West Berlin couldn’t enjoy. And switching between the two Berlins gave him freedom of a liminal kind. He would exchange his Deutsche marks for eastern marks to buy food and painting supplies in the East and take them back to the West. The buildings and streets in East Berlin reminded him of Beijing, but though they were strangely familiar and comforting, it was the cafés and museums in West Germany that attracted the young art student more. He was surprised to find ‘Bauhaus’ everywhere – not the Bauhaus he had learned about back in Beijing, but in other aspects of daily life, such as the pan-European German chain of DIY shops by that name.

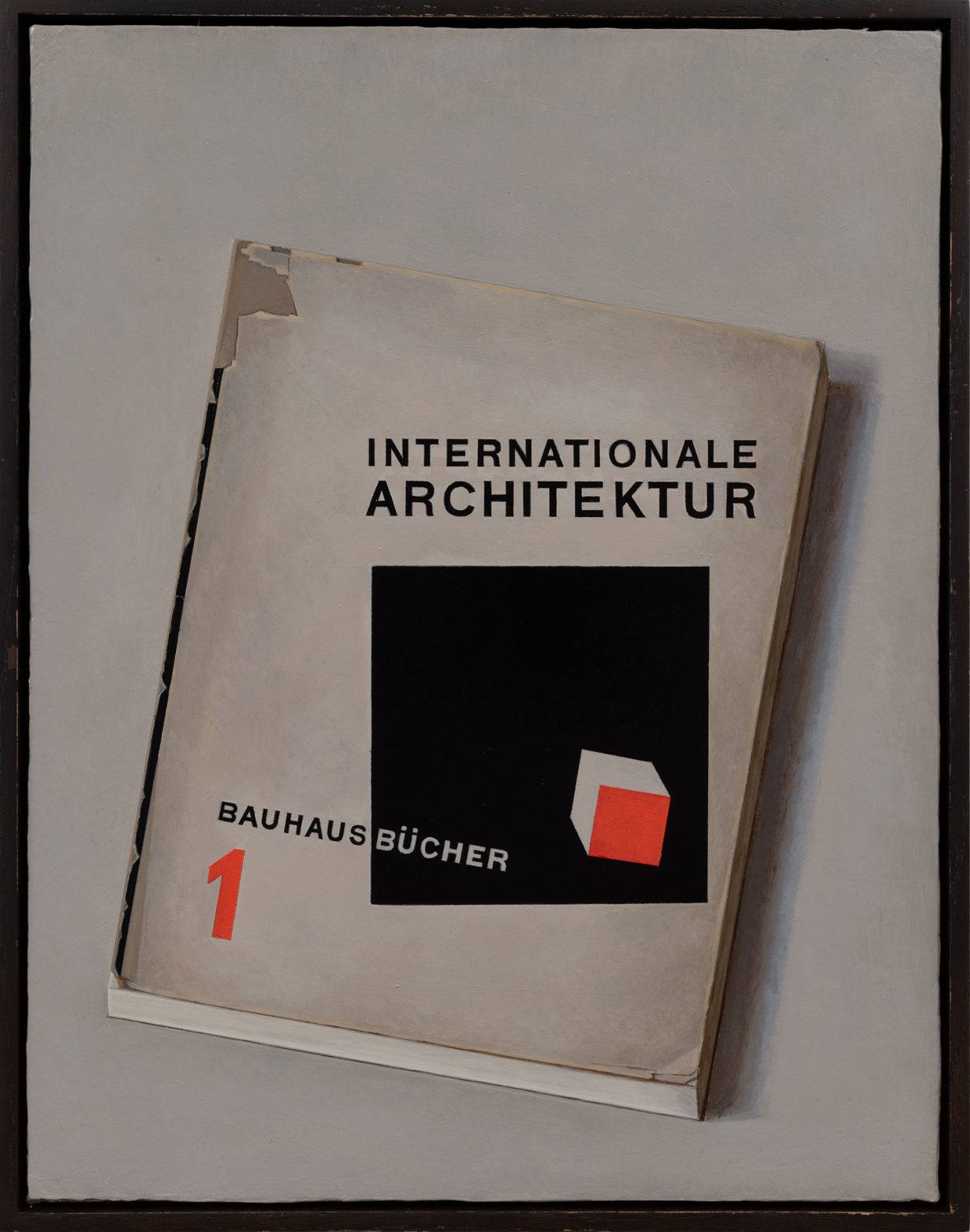

Before enrolling in the mural department at CAFA, Liu Ye studied industrial design at the School of Arts & Crafts in Beijing from the age of fifteen to nineteen. He described the school as a secondhand Bauhaus. Teachers at the School of Arts & Crafts had been sent abroad to study the Bauhaus theory before the Cultural Revolution. They brought back theories and methodologies of European modernism, and taught young design students graphic composition, constructivism, Kandinsky, etc. Mondrian, who would become something of an icon for Liu, was taught as an example of how to draw patterns, but not from the perspective of any broader art history. Needless to say, Liu’s formal training in design left a lasting impact on his later practice as a painter. Instead of Soviet-style painting techniques, the painstaking study of which would have been a basic requirement at a fine-art school in China, his training in industrial design allowed him an unknowing (at the time) ‘shortcut’ to the ideas of modernism. And that ‘secondhand Bauhaus’ education, combined with his subsequent firsthand exposure in Germany, has manifested in a recent series of works devoted to the Bauhaus, of the iconic buildings and book covers associated with the movement, and of Oskar Schlemmer’s ballet dancers. A tribute to the universal qualities of beauty and restraint that characterise the output of the movement and Liu’s own paintings.

Though Liu showed a remarkable talent in drawing as a child, painting wasn’t his first love. Liu’s father was a writer of children’s literature and, perhaps unsurprisingly, the young Liu Ye developed a passion for books and once aspired to become a writer himself. Given that his childhood was marked by the Cultural Revolution in Beijing, Liu had, at the time, an incredibly rare and privileged access to books: both children’s books and banned books that his parents had acquired before the Cultural Revolution and hidden at home. On the flipside, his father knew well about the danger of language and what not to write, and subsequently discouraged his son from becoming a writer in light of the dangers involved. He allowed, however, that he could become a painter.

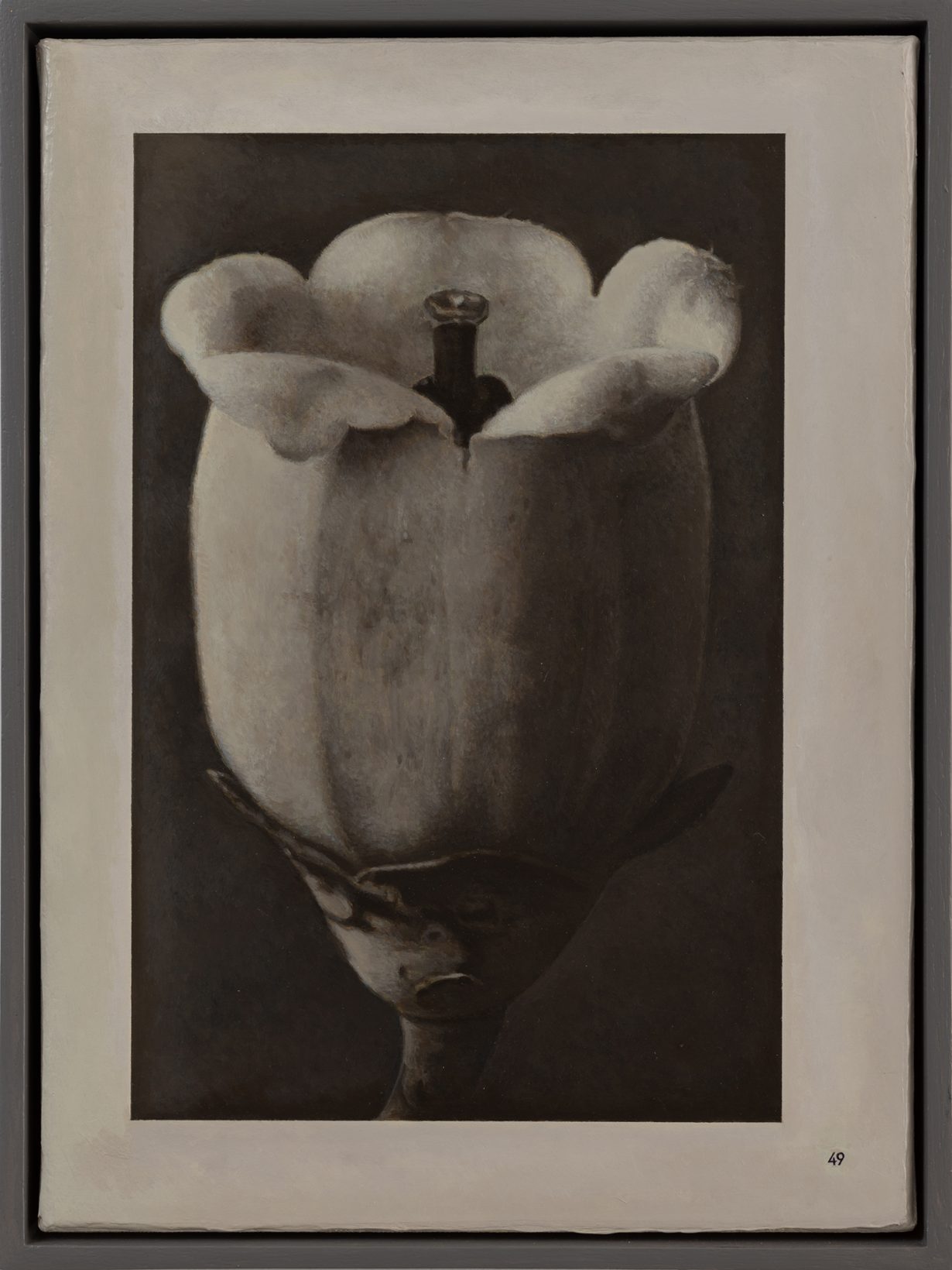

Still, Liu’s love for the literary form echoes through his painterly work. Most obviously, books have, literally, played a part in his paintings since the early days: from the self-portrait Brooklyn (1994) in which he holds a red book next to a Mondrian painting, to the more focused series representing book covers and pages that started around 2013. Particularly striking among ‘The Book Paintings’ series are three renditions of the first page of Lolita (1955) by Vladimir Nabokov. Liu copied the exact image of the page – line by line, word by word – from three editions of the book, printed in 1997, 1959 and 1955 respectively. When we meet, Liu speaks of the rhythm in Nabokov’s words (which he had read in both English and Chinese, but chose to represent in the former) with the same passion and obsession with which he discusses the quality of van Eyck’s brush-strokes. What this speaks to is an ultimate love for language, be it writerly or painterly, in its elementary phonemes and rhythms.

All this might bring to mind the nineteenth-century poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire’s favoured metaphor of the painter as translator, but in the case of Liu, the work transcends any binaries of imitation and imagination. Liu only translates the things that he absolutely loves, taking them from one lexicon to another. In the process, he stays faithful only to the beauty and rhythm of language, not to the original author’s intent, as Nabokov would have demanded (as a translator himself, Nabokov wrote several essays on the subject of translation in which he emphasised that the process should involve total loyalty to the author’s full intentions). In this respect form trumps content. Although in appearing to place an emphasis on the former, and in a way insisting upon it, Liu leaves his paintings wide open for interpretation, confronting experience with a form of innocence (which has, in the past, led the artist to focus on representations of children and children’s characters, such as the Little Mermaid and Dick Bruna’s cartoon rabbit, Miffy).

It was the translator Mei Shaowu who first introduced Nabokov’s novels to a Chinese readership. And his translation of Pnin (1957) is one that Liu read and loved. Son of the famous Peking opera artist Mei Lanfang, Mei Shaowu was the only one in his family of opera artists to delve into the world of written language. Perhaps because of his family background, Mei came to know early what any masterful translator learns, something Liu also learned from his literary family: that a certain rhythm transcends the specifics of language and has the potential to connect beauty in all forms.

Work by Liu Ye is on show at Esther Schipper, Berlin, from 11 September to 23 October.

From the September 2021 issue of ArtReview.

All images © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin.