From Brat to Chappell Roan, this is pop music now: unapologetically girly, increasingly queer, a thing that can be both glitteringly beautiful and also messy and vulnerable

The images paved the way. Gone were the sunflower-yellow dresses, the hazy blue skies, the golden sand; now the images are harsh, astringent, bleached. Seemingly makeup-free in a grey hoodie, Lorde is staring out to you with vacant inscrutability; or, in another video, a naked body straining against a black string hammock; or a writhing figure with a thick strip of grey duct tape sliced through a pale chest. One night she’s performing in front of an ecstatic crowd at New York’s Washington Square Park in a grainy whirl of lights. The next day, footage of the show becomes part of a swiftly uploaded music video, her first in four years. This is pop, after all, a genre whose lifeblood is stage-managed spectacle. The video looks homespun, shaky and unfinished, and that is the point. ‘I’ve spent a lot of my career making these objects that will last through time and be beautiful in perpetuity,’ she told the artist Martine Syms, in an extended conversation about the album. For this, ‘I was like, “No, let this one degrade almost immediately.”’

Lorde’s Virgin, released today, is a document of ephemerality and imperfection; a celebration of the exquisite pleasures and pains of being alive and embodied, rushing towards the edge. Its songs sound jagged and harsh, sexy and tender. There’s a new simple confessionalism to her lyrics that, paired with her trademark breathy vocals, makes some songs feel like a secret whispered from a knowing and occasionally wildly esoteric friend (“I’m a mystic, I swim in waters that would drown so many other bitches”). As usual, the melodies don’t often follow the structure you might expect. Shapeshifter opens with a tense electronic beat before unexpectedly crescendoing into a buoyant, almost orchestral ballad. Clearblue, meanwhile, recalls the experience of getting a pregnancy test “after the ecstasy” to a pared-back beat, only punctuated in Jim-E Stack’s production by sounds of hazy wails in the distance. The singer has said that her albums reflect the drugs she was taking while making them: Pure Heroine (2013) is alcohol; Melodrama (2017) is MDMA; and Solar Power (2021) is weed. Virgin seems to me a ketamine album, a kind of spiky, revelatory record; it’s walking out of a grungy European club into the early morning sun, a film of light dissociation washing over you as you see the world and your own body anew.

Virgin arrives in something of a golden age for pop music and embodies many of its current attractions: the longing for escape; the glitter of spectacle; the rush to feel collective release. I remember the time just before the flood. In 2022 I saw Lorde’s Solar Power tour in London. Tickets were reasonably priced and easy to buy, and though I did enjoy myself, I did not get the sense that I was attending an ‘event’, in the winking, self-referential sense.

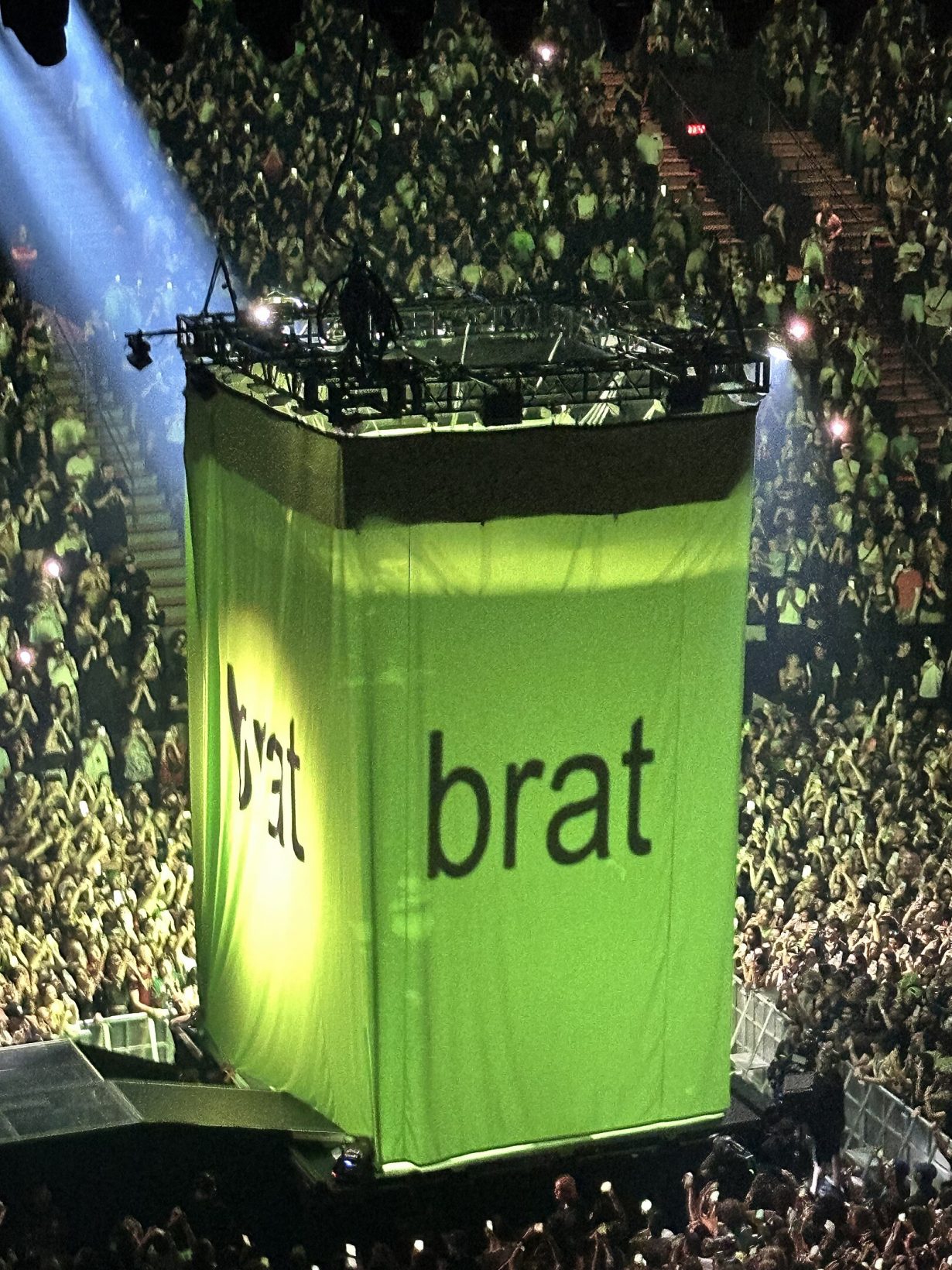

After that came Taylor Swift’s Eras tour, a work of spectacle-cum-performance art that dominated the headlines and raked in billions. Then in 2024 Charli XCX’s Brat defined the summer in the same way Pokémon Go did in 2016 – ie a halcyon time of bodies being silly and carefree together in the heat before the coming of the Bad Vote – while Beyoncé would careen through the air on a horseshoe in stadiums around the world, literalising what has always been core to her image: that she stands closer to the heavens than us mortals. After years of fretting about the inability of new acts to break through, Chappell Roan and Sabrina Carpenter broke down the walls in a shower of glitter. After years of earnest singer-songwriter melodies and moody dark pop, irreverence was back, as was frothy joy. The sounds were insouciant, undone, maximalist.

But as ever, there was a price to pay. Pop concerts became ‘events’ and getting into them has become a merciless and expensive battle with the gods of Ticketmaster. Millions around the world would sit in virtual waiting rooms, watching the timer tick down with hot anticipation before hopping onto their group chats to relay their place in the queue and the seats available and – always – the exorbitant cost. And what were we paying for? All for the chance to experience – as I did in the Eras concert last spring, then the Brat tour last winter – that feeling of being suspended in space and time in a perfect moment of sweaty, communal ecstasy; surrounded by a mass of bodies with whom you feel immense kinship, your collective joy creating something much greater than yourself. As a friend half-joked to me: “Charli really reminded us that we have bodies.”

It is ironic: a genre that in its early years was derided for its superficiality and dishonesty has now become the most popular outlet to experience the real. It echoes the broader pivot towards ‘experience’ also taken by the fashion, art and retail worlds, which has increasingly turned to transience, tactility and scale – grand immersive art, phone-free fashion shows, shops arranged like exhibitions – as a way to compete with the more convenient seductions of the screen. Pop concerts have become a place to lodge a thousand disappointments and turn them into fleetingly and transcendently beautiful moments. We need such places: the disappointments today are legion. The story of the explosive popularity of live music – with its sweat, its touch, its buoyant momentary togetherness – seems to be the mirror image of the story of isolation during the pandemic; concerts as the antidote to loneliness of only seeing the world and other people suspended behind the glassy screen.

This latest expression of pop – unapologetically girly, increasingly queer, a thing that can be both glitteringly beautiful and also messy and vulnerable – has become an antidote to a world broken apart by violent male egos and the hardening of the artificially intelligent machine. This is not to say that it is pure: the rapacious capitalism of the music industry, as exemplified by the twin demons of Ticketmaster and TikTok, has undone that fantasy. But this is the reality we inhabit, and so here we are, grasping for a very human need for connection, joy and love through the meat grinders of profit-maximising megacorporations and the cynical blitz of marketing campaigns. But then again, the story of pop music in the twenty-first century is a story about modern girlhood, and the girls have always known: wading through the mass of contradictions that society offers up to you, holding them all within you to produce something that feels meaningful, is an ordinary feature in being alive.

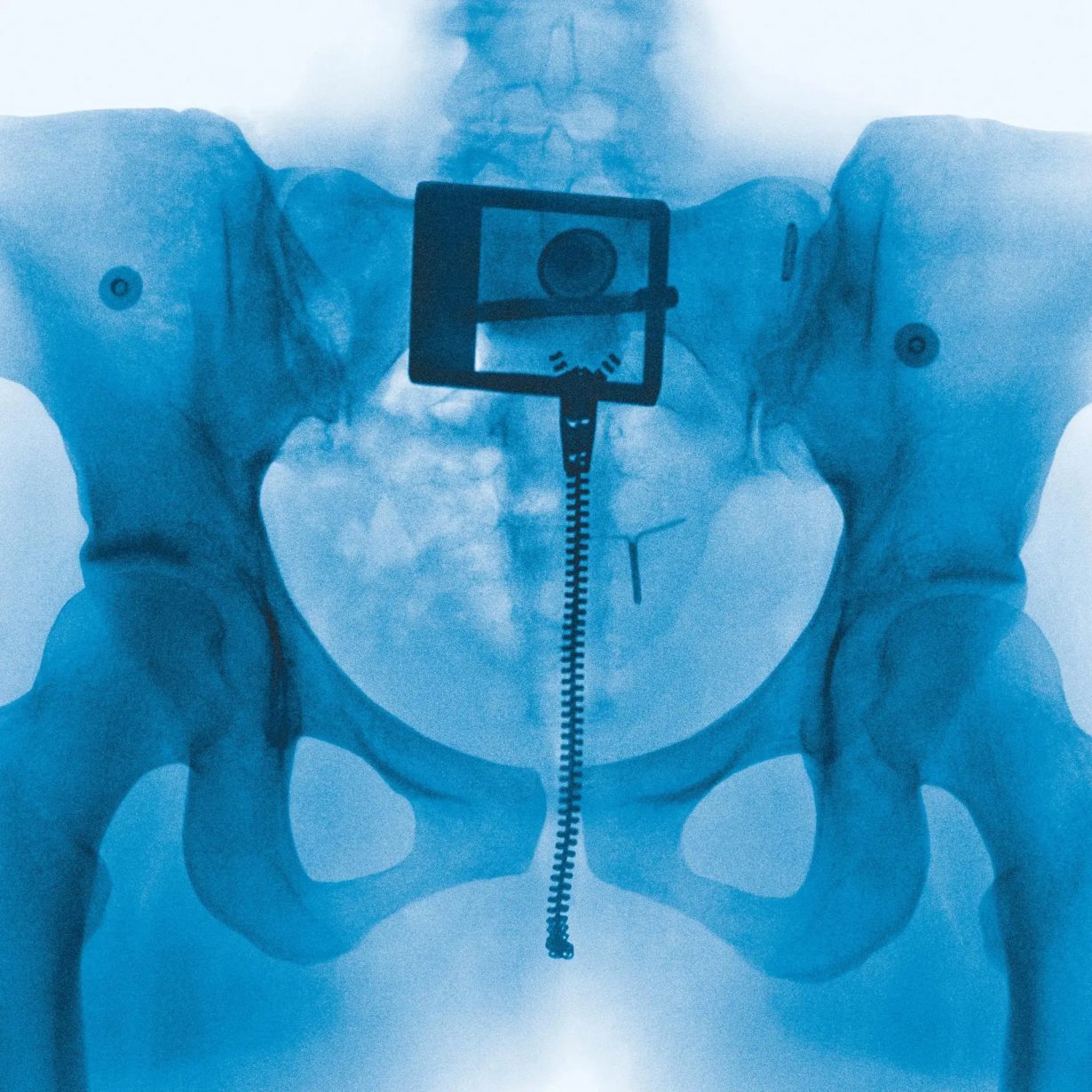

Virgin embraces the zeitgeisty themes of both spirit and flesh. She often sings of her own body: she mourns the time she turned against it in the candid Broken Glass, which looks back at her year of disordered eating; celebrates her “wide hips, soft lips” in GRWM; the “broken blood” she carries from her mother in Clearblue. The album cover is an X-ray of her pelvis with her IUD visible, which plays out like a declaration of self-ownership: there’s nothing more to hide, it seems to say. (That fully arriving back into one’s body can be freeing, expansive and generative has also led to Lorde’s biggest controversy this press cycle, when her statements about her gender experimentation to Rolling Stone – ‘I’m in the middle gender-wise’ – led to accusations of flippant gender baiting. For her part, she said in that same interview: ‘I want to make very clear that I’m not trying to take any space from anyone who has more on the line than me. Because I’m, comparatively, in a very safe place as a wealthy, cis, white woman.’) Meanwhile, on the feral bop If She Could See Me Now, she sings of hearing “the voices of the ancients” in New York, seeing “bodies move like the spirits inside them” and “returning to the clay”. Throughout the album, there are references to going to “the edge”, of falling, of busting the “bars of a window” wide open – the other side of which lies rebirth, until “clearness is all I see”.

Since 2017 Lorde has affixed an adaptation of a quote from Joan Didion’s ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ (1968) to her Instagram bio: ‘The themes are always the same, a return to innocence, the mysteries of the blood, an itch for the transcendental.’ Taken from the writer’s essay about the disaffected 1960s flower children of San Francisco, it echoes both Lorde’s early branding and her appeal as a star who gave voice to generational disappointments and longing. She arrived as a precocious sixteen-year-old who spoke first for a generation not well served by glamour; then a generation rushing into the night in search of perfect places; then a generation tired of the horrors of the city and yearning for the land. Any traces of the ‘we’ of her earlier records have been scrubbed clean in Virgin, an album assuredly about self-reclamation. Being anointed an avatar for precocity and a voice for a generation is, after all, a cage masquerading as something else: “I’ve been up on the pedestal / but tonight I just wanna fall,” she croons in Shapeshifter. In opening song Hammer, she casts off her early reputation as a sage: “I might have been born again / I’m ready to feel I don’t have the answers”. Then, 34 minutes later, on breakup anthem David, the closing ballad, she arrives at what feels like the culminating point and thesis for her latest record. “I don’t belong to anyone”, she sings over glitchy synths; there’s a pause, and then an upward-lilting and extended: “wooo!” It is a statement of self-love and total liberation – it’s also the kind of lyric that will reverberate around arenas on tour this winter. The crowd will move in unison, sway to the beat, sing along to their fallen idol and itch for the transcendental.

Rebecca Liu is a writer and commissioning editor at the Guardian’s Saturday magazine