Recently I have been drawn to a particular type of art. One that gives colour and shape to the feeling of life from the inside. And by that I mean art that articulates the psychological experience of a subject rather than the boredom of being stuck inside all day. Although my renewed interest in the former no doubt stems from the latter.

The representation of an ‘inner life’ might seem like a retrograde artistic project in the wake of postmodernism. It could even sound quiescent in the midst of crises that demand organisation and activism, and I don’t mean to sound a retreat into look-out-for-your-self liberal individualism. But the general consensus that meaning is constructed by relation, that identity is a function of intersecting fields and that a work of art is legitimated by its social or political contexts can be stifling.

The freedom to address a subject that cannot be dictated by, or reduced to, external structures – bluntly, what it feels like to exist – was and is one corollary of artists’ struggle for liberation from the church, the state and the market. That move establishes the grounds for critique: only by taking up a position outside the networks of power can artists report on them. But the freedom to make work without adapting it (consciously or unconsciously) to the expectations of an audience is also the principle that animates art. And that distinguishes it from the expression of a collective ideology, which is to say propaganda. As the novelist Álvaro Enrigue put it in a 2016 interview with Bomb magazine, ‘a writer worried about reception is cooking a dead book’. The same is true of artists cooking up artworks.

How courageous an artist still has to be was brought home to me by Marguerite Duras’s Les mains négatives (1978). The short film captures Paris at night through the back of a car window: neon boulevards overlaid by a spoken monologue on love and loss. Halfway through, I gave up trying to piece together the narrative. The film makes no concessions to the viewer, does not participate in a community, does not contribute to a debate. Yet this is not heroic self-projection on a grand scale but a modest assertion of the right to an interior life. A familiar landscape is distorted through the prism of someone else’s mind, and in the nature of this impulse – using words and images to structure a feeling rather than advance a proposition – I found something like consolation in my own solitude.

Artists such as Ian Cheng, Philippe Parreno, Anna Tsing and Haegue Yang have in recent years been preoccupied by the radical unknowability of nonhuman intelligences; Duras’s film affirms the irreducible strangeness of other humans. I wanted more of this, so sought out Ben Russell’s video investigations into altered states. In Trypps #7 (Badlands) (2010) we watch a young woman on acid bliss-out in the Mojave desert; in Black and White Trypps Number Three (2007) we watch moshing kids at a punk gig enter into a trance; his recent La montagne invisible (2019) is inspired by René Daumal’s unfinished novella Mount Analogue (1952), which describes an expedition to a mountain that exists only in the mind. It wasn’t quite the same hit – Duras’s fragmentary film-poem is more to my taste than Russell’s psychedelic ethnography – but I was still excited by this same commitment to the representation of interior states that are unreproducible. It would be possible to discuss Duras’s film in theoretical terms – with reference to the flâneuse, perhaps, or psychoanalytic principles of identity formation – but this would be at best superfluous to its effect and at worst a violence against it. Similarly, Russell’s work resists the idea that the audience can fully understand their subjects’ interior lives by fitting them into the proper contexts. Which is, after all, precisely the kind of scientistic assumption that thinkers like Jean-François Lyotard rejected when contesting that art must resist recuperation into the dominant modes of thinking.

The corollary of this was that I did not feel obliged to define myself in relation to these subjects, a liberating experience that might explain the aforementioned consolation. The paradox is that by asserting both their subjects’ freedom and my own, these films generated a much stronger sense of connection than any number of works that make explicit appeal to my politics. Yet this still came as something of a surprise to me. Haven’t I suffered enough confessional poetry? Am I not allergic to autobiographical art? Don’t I endlessly complain about peoples’ determination to air their disposable emotional experiences on Instagram? But broadcasting our feelings isn’t the same as structuring them, and in a culture without private spaces we are reduced to what we see of ourselves reflected in others.

What appeals to me about the above films might simply be that they disregard the rules of an attention economy based on that which is – in both the psychological and smartphone senses – easily shared. Artistic communities online offer an important refuge from the vagaries of the market, among other things, but that sense of shared purpose quickly transforms into a need to be noticed and affirmed. In the context of artistic production, the danger is that this is internalised and that the artist starts unconsciously to produce work that is liable to generate the instantaneous approval of the community: art that is relatable, that gestures to recognised causes, that positions itself within an identifiable constellation of other works and meanings.

This assimilating tendency operates in both directions, with eccentric work quickly ‘reclaimed’ for centrist causes. The idea for this text was planted by an unexpected encounter a couple of years ago with a series of Mike Kelley’s Kandors (1999–2011), the architectural models he based on the miniaturised city that Superman preserved in a bell jar. I remember being irritated by a wall text describing these sculptures’ celebration of American subcultures, an easily digestible narrative that is flatly contradicted by even cursory attention to the work. The bell jar is a symbol of disconnection; the city state is the only link to Superman’s home planet, which was destroyed by an evil maniac; comic book obsessives are not traditionally the American children most perfectly adjusted to their peer groups; Superman, who lived a double life and never revealed his identity to anyone, kept the city in the only place he felt safe, which he called his fortress of solitude.

Kelley’s fragile worlds are deeply personal expressions of anxiety and existential threat, to which any well-intentioned curatorial dignification of folk art or marginal fraternities must defer. That the artist used the materials to hand to articulate these feelings doesn’t make him representative of anything beyond himself, nor does his entry into the canon serve to elevate cultures that might prefer to remain underground. Which is another way of saying that these are important works of art because they excite the feeling of alienation, not because they are symbolic of alienation. Rosanna Mclaughlin has previously written in ArtReview of how the beatification of Ana Mendieta glosses over the violent contradictions that make her work so powerful, and the characterisation of Kelley as some kind of envoy from blue-collar America also reduces the artist’s achievements to those of a diligent cultural attaché. Recruiting Kelley to a cause sympathetic with the artworld’s liberal sensibilities – that alienation should be represented alongside nonalienation, as if it were a minority ethnicity – defangs his work. Subsuming art into the field of cultural politics, by reducing works to a cause they are assumed to stand for, reveals art’s own ontological crisis. (And might also be a battle in the war for primacy between individuating artist and systematising curator.)

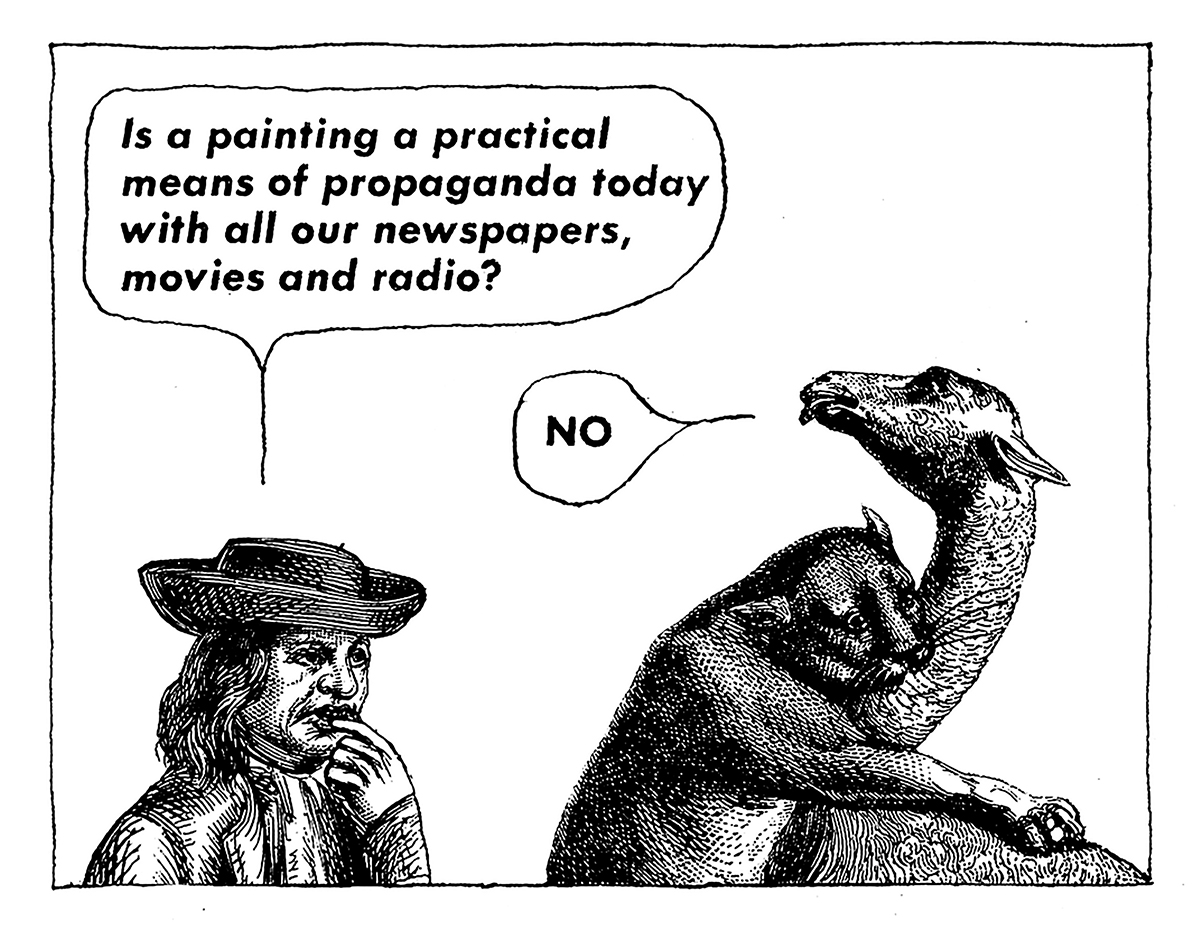

The urge to hitch every work to a principle begs the same question posed by an Ad Reinhardt cartoon: ‘Is painting a practical means of propaganda today, with all our newspapers, movies and radio?’ The answer then was ‘no’, and this is ever more the case today, whatever our feelings towards the cause and however ludicrously the artworld inflates its own cultural influence. Reinhardt asserted art’s freedom by poking fun at the idea that the CIA had no better instrument for the enforcement of America’s ideological principles than the New York School. Today, I have come to be suspicious of press releases presenting art as the instrument of a cause. Not because art should not be political but because, to repeat a phrase that is often repeated, but never quite enough, all art is always political. When the curators of a biennial make explicit their solidarity with a cause, it can sometimes (not always) risk supporting the brand of the festival’s sponsors by invoking freedom of expression without meaningfully testing it.

The freedom to articulate one’s own point of view is the precondition of independent thought, because it establishes a subject position. Józef Robakowski’s Z mojego okna (From My Window, 1978–99) collages two decades of footage taken from his apartment in Łódz ́ with idiosyncratic descriptions of the residents he sees below. ‘Our house is our corner of the world,’ Gaston Bachelard wrote in The Poetics of Space (1958), and so Robakowski invites the viewer into a space that is very literally constructed by the state – on the ninth floor of a tower block in a Soviet housing estate – but is also incontestably his own. From this position he is able to observe the society that surrounds him and to comment upon the changes that take place in it.

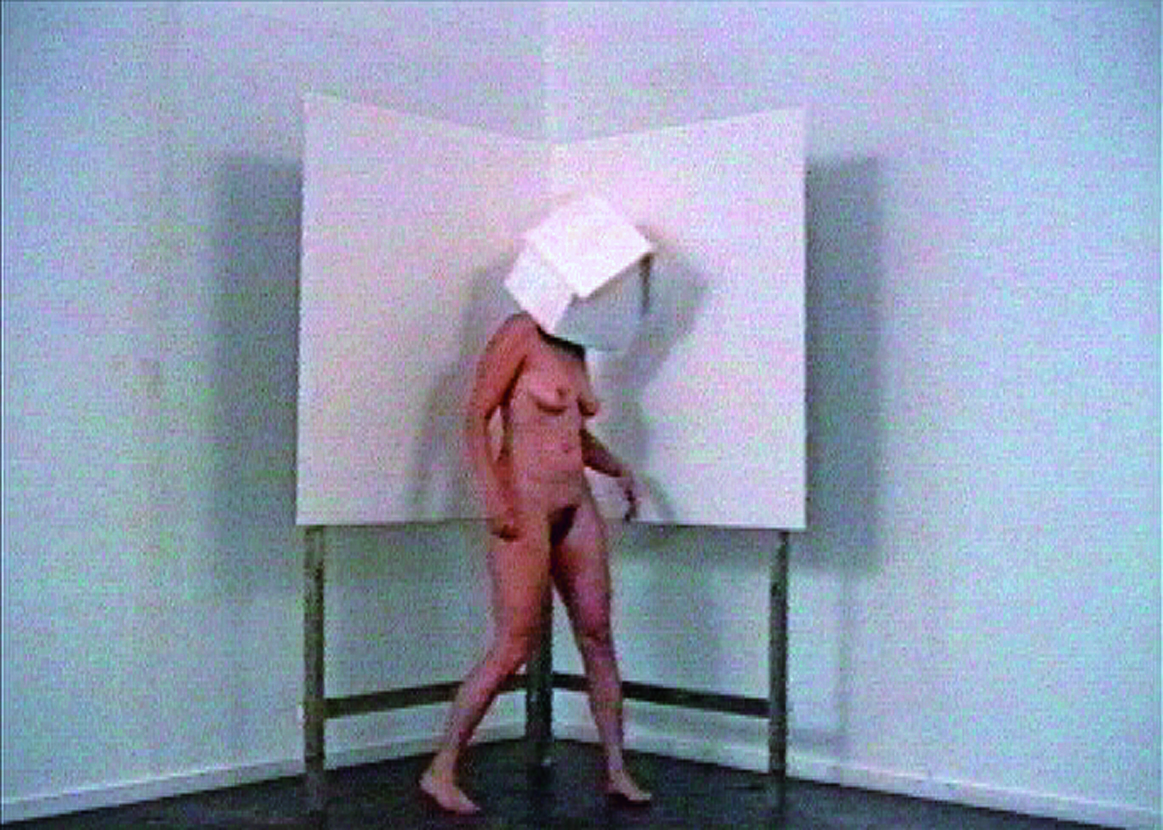

It might be that the excluded are generally better at articulating interiority. Born into a set of conditions in which they feel free, members of the majority have no need to define themselves in opposition to them. Monica Bonvicini’s Hausfrau Swinging (1997), in which a woman with a house for a head bangs it against a drywall corner, communicates the violence required to free oneself from those structures. But if the task of contemporary art is to be one of reconstruction, as Hal Foster has recently suggested, then artists also might show how it is possible to build new ones. Interned in a Nazi labour camp, Jonas Mekas learned what it means to have one’s individual humanity denied: the extraordinary delicacy with which his diaristic films are stitched together attest to the labour of constructing a free experience of the world. To dismiss this kind of self-creation as indulgent is a symptom, not a renunciation, of privilege.

If there is a vocational solidarity in art, it consists in protecting the freedom of artists to construct their experience of the world independently. In an era in which selfhood is constructed by the panopticon of social media, to articulate our feelings in a fashion that does not appeal to an audience might be an act of resistance. Art is uniquely good at representing this complexity, and we look to it because we intuitively understand that we are tangled up with other lives in ways that cannot be expressed in conventional logic or language. Against this, other academic disciplines offer no more than a posteriori explanations of art’s bright revelation that we each construct our own position in a field unified by consciousness. Or, as Chantal Akerman more elegantly phrased it: ‘the more particular I am, the more I address the general’.