What will an artist known for confounding expectations bring to the loaded symbolism of the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale?

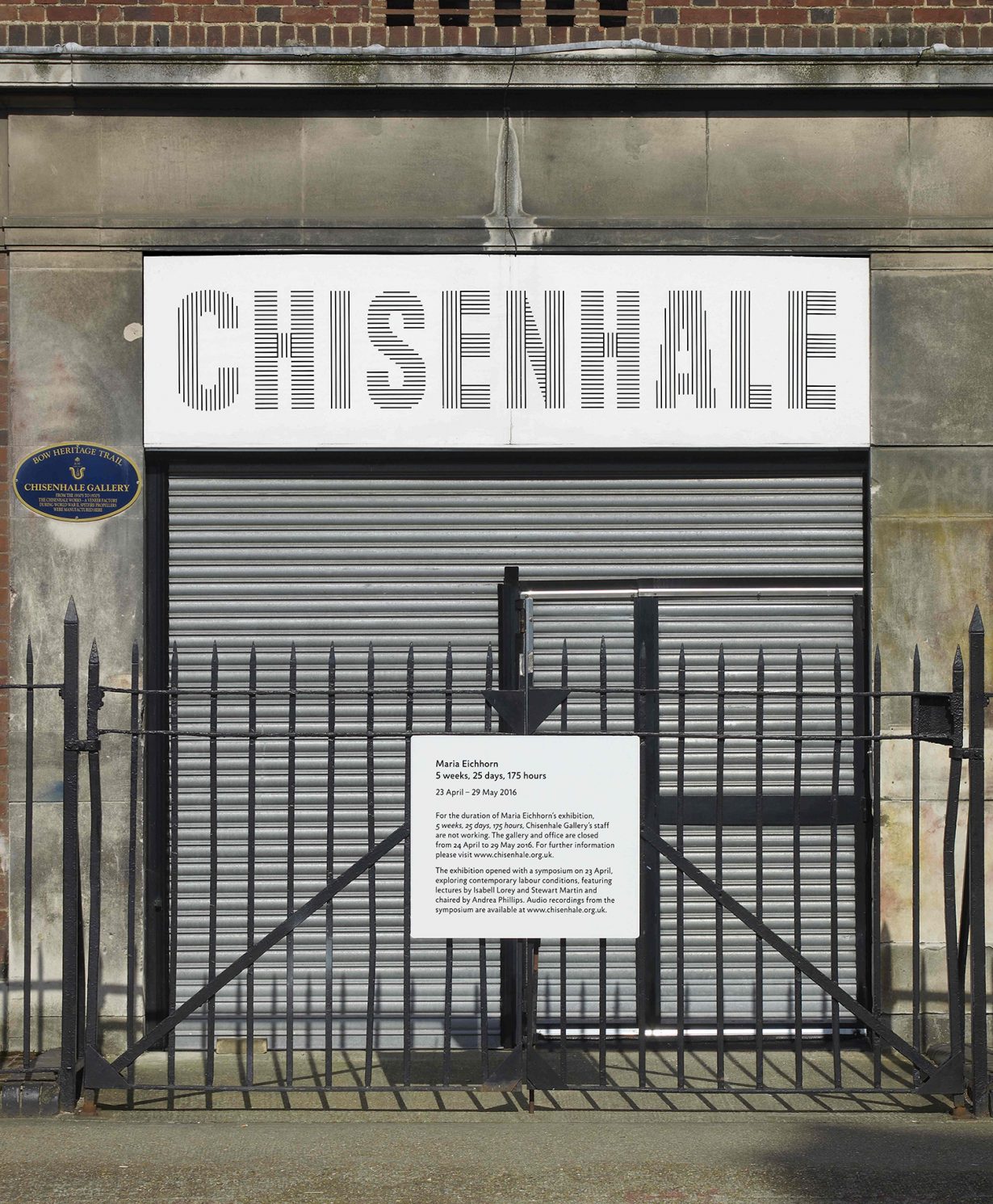

‘The work is accessible. It can be experienced both conceptually and – physically and in motion – on site.’ That’s Maria Eichhorn, talking to curator Yilmaz Dziewior about her planned work for the German Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. Dziewior, the curator of Eichhorn’s show, had asked her for three sentences describing her intentions; the artist, characteristically, gave an economical response. It’s notable, nevertheless, that Eichhorn stressed acces- sibility (perhaps even for nonattendees). This is the artist, after all, who when she was invited to exhibit at London’s Chisenhale Gallery in 2016 responded by closing the gallery for the duration of her show, augmenting the gesture with a symposium on labour conditions in the artworld. The following statement might be a hostage to fortune, but Eichhorn’s Venice exhibit is likely to be something you can actually see.

As seasoned Eichhorn-watchers will also guess, her fourth and most auspicious appearance at the Biennale is also likely to be, on some level, engagé. Some hints: in her conversation with Dziewior, published on the German Pavilion’s dedicated website and conducted last year (approached for an interview by ArtReview, Eichhorn was regretfully too busy finessing her Venice show), the artist expressed interest in artists who’d responded to the pavilion’s history – and thus, given the fascist architecture of the 1938 edifice, Germany’s dark past. She also zoomed out to consider the biennale as a whole: why it began, which countries it excludes, whether it remains a political metaphor for international relations and how art might be ‘produced and received more independently of… constructions of national identity’. That aside, guessing might be a fool’s errand given the immense formal variety of works that Eichhorn has created over the last 35 years, from paintings to skips to near-invisible interventions in the social fabric.

Then again, though, her projects share points of reference, for all that Eichhorn has said she resists summing up her own practice. In an essay for the catalogue raisonné that accompanied a 2014 show at Kunsthaus Bregenz, Alexander Alberro and Nora M. Alter arranged Eichhorn’s art under the dual signs of ‘displacement and redirection… interruptions that develop over time and destabilize normative forms’, and noted that she’s regularly applied this approach to institutional critique. The artist whose first exhibited work, Redundant Stairs (1987) – made in her mid-twenties – was a large blue structure blocking the stairs of Berlin’s main art school, the then-Hochschule der Künste, was, by 2013, presenting a white-on-white, barely legible wall text in Paris’s Jeu de Paume that gave the venue’s address, along with a number of free tickets to the other shows on at the same time. As with her Chisenhale show, a critical refusal to meet the artworld’s expectations (exhibit visibly visual art) is accompanied by a countermanding expression of the gift economy.

These acts of generosity towards a wider public – pointedly larger than the artworld’s cognoscenti – have speckled Eichhorn’s career. In 1993, for example, when she was invited to exhibit at the art centre attached to Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, her contribution was to ensure the resuming of restoration work on the castle itself, using her production budget to reconstruct its northwest tower. In 1995, in By Train from the Central Train Station in Leipzig to All End Stations and Back Again, she advertised her offer of free train tickets in a newspaper, a raffle determining 21 winners. The following year, for Marram Grass on a Public Beach, Eichhorn planted grass on a public beach near the Louisiana Museum in Denmark as a bulwark against shore erosion.

What such works do not engage with is the commodity fetishism of contemporary art. When Eichhorn deals with money, it is generally in a way that does some public good or that refuses profit margins. In 1997, invited to participate in Sculpture Projects Münster, she used her allotted funds to buy a vacant plot of land in the area, which she resold some months after. Under the terms of the sales agreement, the money raised went to renovating buildings in a street dedicated to affordable housing, effectively a gift to the local tenants’ organisation. In 2001, for a show at the Kunsthalle Bern, she funded repairs to the building, explored and exposed the institution’s financial history, and sold shares in the building to help secure its financial future. The following year, invited to ‘exhibit’ at Documenta 11 – whose curators must, by this time, have engaged Eichhorn with their eyes wide open – she used €50,000 of production fees to establish a limited company, Maria Eichhorn Aktiengesellschaft. She set this up, however, in a circular fashion such that all the shares, rather than being offered publicly, were transferred back to the company, creating a closed loop with no nefarious capitalist activity possible.

Such projects, usefully, could also reach and be grasped by viewers who only heard or read them described. What is espoused here, aside from Eichhorn’s ethical mindset, is the surprising amount of wiggle room within the artworld as both a site of physical exhibitions and a marketplace of ideas, and the variety of fertile grounds for inspiration – even in dusty documents – if you’re a canny, strategic thinker like her. Actual, if sometimes relatively symbolic, social change is possible using art’s bloated, cash- lined, pretension-heavy infrastructure. (Meanwhile, running counter to the seeming sombreness of her designs, note that when Eichhorn’s announcement as Germany’s artist for Venice was released, attention was drawn to her subtle sense of humour. As a resident in Germany, I must admit that the bar for what constitutes ‘funny’ is lower here than in some other countries, but certainly some of the things Eichhorn pulls off, and the way she twits the artworld, can scan as dryly witty.)

Not infrequently, it seems that Eichhorn’s modus is to see what that infrastructure will permit. In 1999 she began her ongoing series Film Lexicon of Sexual Practices, an expanding collection of pornographic films, from which – in the gallery – the viewer selects one to be projected: choose from, say, Anilingus, Ear Licking, Milk Bath or Breast. In this viewer’s experience, the experience is awkward and complicated, allowing the uncommon register of audience embarrassment (rather than being embarrassed for an artist), if conceptually rich. The gallery context troubles the status of pornography, which is legally supposed to be distinct from art; the porn, filmed starkly and in closeup, is not arousing anyway, and the whole has a paradoxically pedagogical air. For the aforementioned Alberro and Alter, the work is concerned with the institutionalisation of sexuality: the wide spectrum of sex reduced to a bunch of templates. Eichhorn’s collection points, seemingly, to whatever freedoms and kinks might lie outside it.

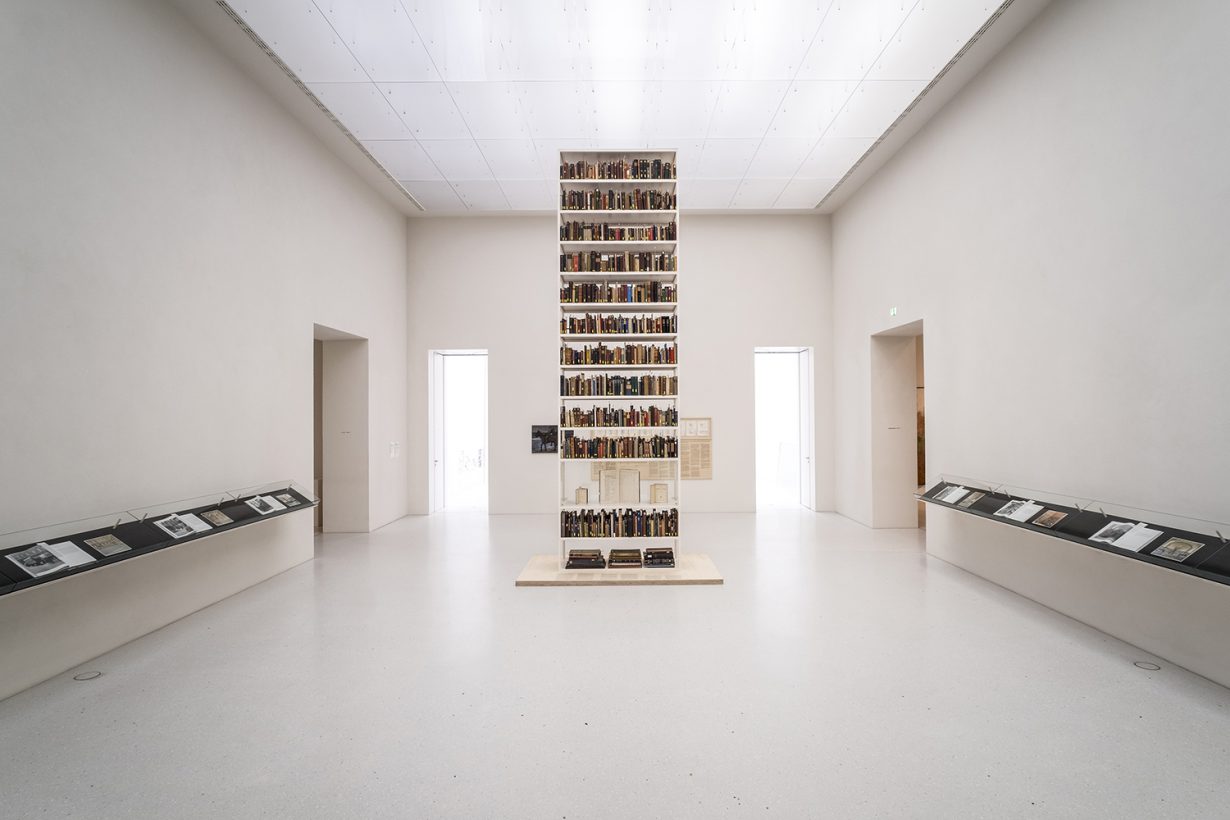

This work points to the potentials of an archive or collection of documents – as, of course, do the legal papers that Eichhorn has used to real-world effect elsewhere – and a uniquely powerful expression of this is her ongoing research project Rose Valland Institute, which debuted at Documenta 14 in 2017 and constituted Eichhorn’s last major presentation at a top-tier international expo. According to its own website, this endeavour ‘researches and documents the expropriation of property formerly owned by Europe’s Jewish population and the ongoing impact of those confiscations’, and is named after the art historian who recorded Nazi lootings among Paris’s Jewish population. The aim is not merely to explore the past but to change the present: it calls for the public to share researches into looted artefacts that have not been restored to their owners and their descendants. This is an art that deals with objects, but one that is light years removed from the speculative, financialised relationship to objecthood that permeates the artworld; one that leverages the surrounding structure, and its potential to meet a large audience, in a productive, clearsighted, principled manner. Whatever Eichhorn has planned for Venice and however it might relate to Germany’s chequered history, you can expect it to adhere to those principles too.

Work by Maria Eichhorn is on view at the German Pavilion in the Giardini as part of the 59th Venice Biennale, 23 April – 27 November