“How is boredom interesting, or important?” Berlin-based artist Tobias Zielony asks me this question in a café near Checkpoint Charlie, surrounded by other customers neurotically checking their smartphones or rushing out with coffees to go.

I reflect on Zielony’s question, and think of the subjects of his photographs and films from the early part of his career – usually listless, seemingly purposeless young people living at the fringes of society. Then I think of boredom itself, and realise that in a productivity- hacking, network-cultured era, it has become increasingly rare, even suspicious, to do nothing. Boredom is feared. It’s a state of being or not-being largely relegated to have-nots; those without access to the infinite distractions of Western society.

Along with social marginalisation and an exploration of documentary photography’s ideologies, boredom is an important, if perhaps invisible, theme running through Zielony’s oeuvre. He shoots the disenfranchised and the places they live and work – derelict housing projects, desert slums, bus stops, gas stations – in limbo, loitering, posing, being bored. “It’s very difficult to depict boredom,” says Zielony, who was born in Wuppertal, Germany, in 1973 and is one of five artists representing that nation at this year’s Venice Biennale. (He is, by the way, clearly not bored – approachable and friendly, with almost Nordic looks and an occasional deep chuckle, he exudes a combination of calm and hyperalertness, as if he’s continually processing contextual information but never getting ruffled.) “I even thought boredom was an act of refusal or rebellion, but I’m not so sure about that any more.”

Zielony’s fascination with the edges began during two courses of study – the first in Newport, Wales, during the late 1990s studying documentary photography and the second a degree in fine-art photography at the Leipzig Art Academy. It was at the former, an institution geared towards editorial reportage in a working-class city, that Zielony “noticed that the way I photograph and the stuff that interests me doesn’t have so much news value”, leading him intentionally to place his ambiguous, ambivalent works into an art context and head to Leipzig and the international artworld. Ambivalence and ambiguity are, of course, the opposite of the clear narratives and digestible stories that photojournalism demands: “I’m trying to create a nonlinear narrative outside the time- or story-based one,” says the artist. He succeeds in pinning us to the images themselves, even if they do often obscure the boundaries between documentary photography, photojournalism and fine art. Several times in our conversation, in fact, Zielony speaks slightly disparagingly of journalism and journalists – citing unprepared interviewers, misquotes or, more importantly, that it’s difficult to photograph or film subjects who have been previously disappointed by a prior photojournalist’s lack of engagement or time. At times, however, I wonder whether the artist perhaps also harbours a certain tense ambivalence towards a trade and visual culture that lies so close and yet so far from his own.

Zielony says he gains his subjects’ trust by not judging or moralising, by taking time and by not trying to ‘save’ anyone, even if he’s twice been asked to be a youth leader through his photographic work

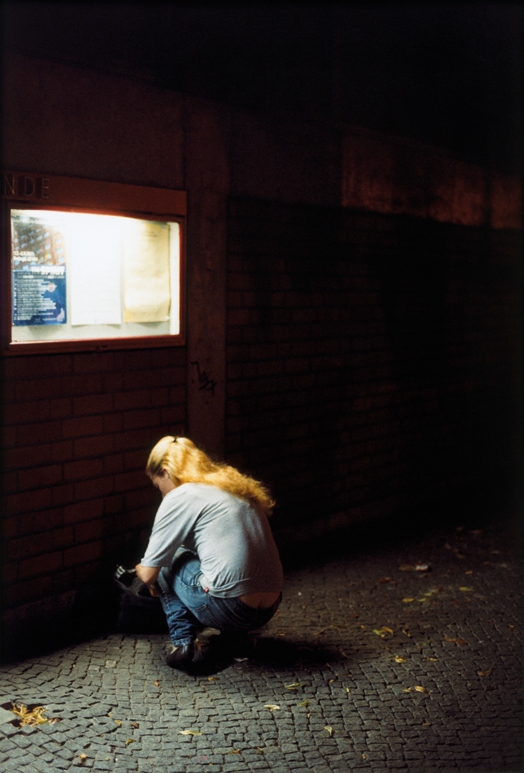

His subjects remain anonymous, ‘stories’ appear as fragments; socially loaded situations are aestheticised. We never learn the identities of the people in Zielony’s Trona series, shot in the meth-addled ‘armpit of America’ in the California desert in 2008. Nor the First Nations people – mostly men, but also families – from in and around the Canadian prairie city of Winnipeg in his Manitoba series (2009–11). Jenny Jenny (2011–13), a haunting ensemble of photographs and a film depicting several Berlin-based prostitutes and their milieus, offers only hints of where, when, how and who. Instead we see representations of a woman in her underwear with a jaggedly scarred belly, a concrete staircase leading into a desolate housing project by night and a young woman we assume, from the title, is named Steffi. Other series show peripheries and their people in Poland, the outskirts of Rome or Naples, Marseilles, Dortmund and other places. Some images seem candid, others feel posed, as if the subjects were jumping at the chance to be granted a voice, a place in modern image culture, perhaps for the first time. Zielony says he gains his subjects’ trust by not judging or moralising, by taking time (for Jenny Jenny, 18 months) and by not trying to ‘save’ anyone, even if he’s twice been asked to be a youth leader through his photographic work. His motivation? “With the young people in Wales or Manitoba, it was more that these people are as important as anybody else. They form daily life and society, too, so why not talk about them?”

Here arise the perennial issues of photography’s ability or inability to depict ‘truth’ or act as a window on or mirror to reality – as well as ethical questions of the author’s infiltration of a situation, the subjects’ complicity and thus coauthorship, the viewer’s interpretation. Some series (especially Jenny Jenny, one could argue) can be seen as purely voyeuristic; others come uncomfortably close to poverty porn, even if the subjects are granted a certain grace and dignity. Zielony, who considers his work not documentary photography but an exploration of its history and ideas, is well aware of these problems, bringing up names like Marxist artist and art theorist Victor Burgin, who at first saw fine art and documentary photography as mutually antagonistic.

Is boredom indeed rebellion, or simply an inevitable byproduct of marginalisation and poverty? And does depicting it reveal a social problem to be solved, or condemn the subjects to remain forever in their disenfranchised states?

Back to the notion of boredom – is it indeed rebellion, or simply an inevitable byproduct of marginalisation and poverty? Does depicting that boredom reveal a social problem to be solved, or condemn the subjects to remain forever in their disenfranchised states? Does it simply make viewers into apathetic recipients of yet another anaesthetising wave of images? Zielony’s pictures are haunting, his nocturnal overexposures of people and places eerily beautiful, but they don’t solve photography’s perennial dilemmas. They push our image-weary buttons and, as the artist says, “ask what photography can do”.

Lately Zielony seems to be going beyond boredom – filming and photographing far less lassitude and more proactivity, as well as playing with new aesthetic approaches. In a recent exhibition featuring his films at Berlin’s KOW gallery, the newest works represented a break in subject matter and style. A film shot in Ramallah under the auspices of a Goethe-Institut scholarship is a loose remake of Kenneth Anger’s 1965 Kustom Kar Kommandos. Zielony’s slick Kalandia Kustom Kar Kommandos (2014) sees two Palestinian men gently polish, then drive, a vintage Volkswagen to a soundtrack of the Paris Sisters’ version of Dream Lover (1964); the result is a vaguely homoerotic, fetishistic homage. It was the first time Zielony had worked on a storyboarded production, and the first time he lent his ‘eye’ to a camera operator.

When I ask about his upcoming appearance in the German Pavilion – curated by Florian Ebner, with artists assembled to explore the concepts of contemporary image culture and distribution – Zielony says “he can’t say much” (discretion is another reason we’re meeting in a cafe, and not in his studio nearby, which apparently contains a model of the pavilion. He also only moved in a couple of weeks before). But he can reveal that what will be on view in Venice will primarily be photographs featuring refugee activists currently living in Germany. “They’ve illegally left the camps in German cities and formed a protest movement. They use media to have a bigger impact. In a sense it’s a collaboration, really,” he says.

‘Collaboration’ is a loaded, interesting word in this context. Zielony may be heading into what is for him new territory, illuminating more overtly political issues occurring in more familiar locations, and most importantly (and problematically) taking more agency. His voice becomes more passionate. “At the end of the 1990s we had [Fukuyama’s] The End of History, but now history is coming back with a bang. Look at the Arab Spring. You can’t just sit and think about simulacra – even the war in Bosnia was a challenge to theory at the time. Some political issues are political issues for a reason.” His words again raise old questions of what realities photography is capable of not only depicting but also shifting (at the very least in public consciousness); what art may or may not be capable of in terms of “real” politics, especially in the delineated space of a biennial. Hito Steyerl, one of Zielony’s coconspirators in the German Pavilion, has interestingly written that ‘the only real documentary image is the one that shows something that does not yet exist and maybe come[s] one day’. Something to consider as we await an exhibition that will likely be far from boring.

Watch Zielony’s short film Kalandia Kustom Kar Kommandos, from 2014.

This article was first published in the May 2015 issue.