The Indian artist confronts the Eurocentric modes of communication that shape our social, artistic, technological and political environments in an exhibition that refuses to comply with this vernacular

mOTHERTONGUE is fuelled by anticolonial and anti-institutional rhetoric, challenging the structures that define modern life and the artworld. Housed in multiple gallery spaces, the exhibition encompasses performance, video, sculptures and drawings that encapsulate the past two decades of Mithu Sen’s artistic practice. Frequently using the prefix ‘un’ in her video works, wall inscriptions and ‘legal’ contracts, Sen subverts the languages that define and limit the lives of refugees, migrants and artists – both linguistic (in particular the supremacy of English) and visual (examining the dominance of the Western gaze). At the entry to the exhibition, the artist’s declaration Un-acknowledgement (2023) is projected on the wall, signalling her intention to withdraw from ‘the charades of inclusion and artifices of language’.

As though arranging a mind map, Sen inscribes annotations and tapes lines across the walls between works, stringing together ideas about cultural identity and gender through words and images. Across the dark grey walls of the dimly lit gallery space, videoworks and drawings are interconnected by led light strips. Each of the works explores aspects of communication within personal, artistic, academic and bureaucratic contexts. The eight-channel video Be beyond being (2021), for example, documents Sen ‘Zoom bombing’ into live-streamed lectures at Yale University’s ‘London, Asia, Art, Worlds’ conference, interrupting the discussions like a computer glitch. Other overlapping sounds permeate the space – an evacuation drill, buzzing tattoo gun, a sad trombone sound effect – create an overarching disorienting sense of anarchy. Scattered neon led emojis installed on the wall between the videos – a speech bubble, rose, paper plane and a red hand – symbolise a ‘universal’ visual language used in casual social media communication, marking an unspoken narrative thread that visitors are invited to decipher.

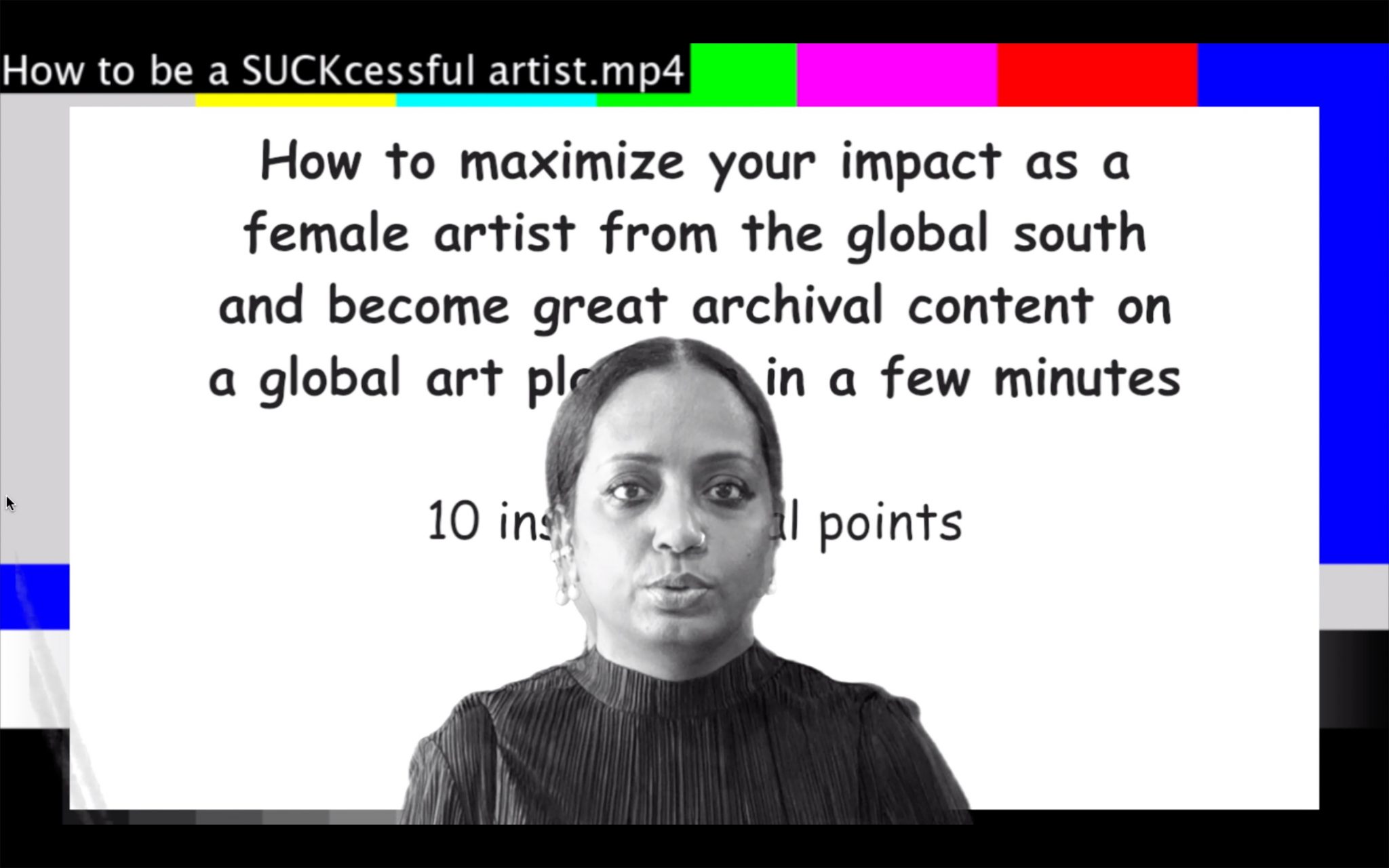

Tracing the paths of the led lights, visitors encounter Contracts #2 #3 #6 #8 #11 #17 #21 #24 (2018–23): multiple framed legal agreements replicating the Indian Non-Judicial Stamp Paper format (commonly used for commercial agreements, powers of attorney and property transfers) and which propose a pseudo contract between the artist, the works and the audience. Several single-channel videoworks, like How to be a SUCKcessful Artist (2019), mockingly reflect on the kinds of performative acts that women of colour need to enact in order to gain exhibition opportunities within museums and galleries. Ephemeral affair (2006) and For D(e)ad (2023) are black-and-white videos that feature closeup shots of Sen’s face and eye respectively, in which the artist makes facial expressions of human pain: in the former she visibly reacts to a violence enacted out of camera shot, while in the latter tears leak from her open eye, suggesting some internalised emotion.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, a sense of violence pervades. In the second white-painted gallery space, single bronze dismembered body parts hang from near-invisible threads along a wall in We unfinish each other (2017), which is presented alongside Unlynching: You never one piece (2017), a cabinet containing collected objects, one for each year since the 1947 Partition of India, during which around one million refugees were killed. A plastic doll’s arm, a glass eye resting in the bowl of a soup spoon, a metal lock, become quietly macabre allusions to the enduring trauma of genocide. In a corner of the room, Unbelongings (2002), a knotted clump of long hair, hangs from the ceiling. While it is just one work in Sen’s series of the same title that looks at long hair as both a symbol of feminine identity (while attached) and an object of disgust (when no longer attached), here, shown in the same space as the bronze body parts, it behaves as a simultaneous reminder of gendered violence and the anonymity of victims.

Acts of translation are explored in an adjoining room accessed through clear PVC strip curtains, where a single screen plays the film I have only one language, it is not mine (2014), in which Sen interacts with a group of orphaned children in Kerala. The footage, altered by high contrast settings to appear as if outlined in red ink, shows the children speaking Malayalam while Sen communicates in a fabricated ‘other-tongue’, as well as hand gestures, to examine methods of communication in spaces where there isn’t a shared verbal language.

One of the most visually striking works presented here is UnMYthU: UnKIND(s) Alternatives (2018): a nearly 4m by 12m installation that includes five largescale drawings surrounded by five smaller drawings, all framed in backlit boxes. They depict naked skeletal bodies alongside religious and political imagery, such as a lotus and refugees on a boat. A mind map of red hashtag words in decal – including ‘#xenophobic’ and ‘#native mutant’ – branch out from the drawings. Shown alongside this installation is a 25-minute video titled Alexa (2018): filmed in front of this work, it presents a performance in which Sen asks Amazon’s Alexa AI technology questions in her ‘other- tongue’, as well as pointed queries in English like “Alexa, what is artist?”, “Are you a sexist?” and “Are you a racist?” As Sen’s frustration grows with Alexa’s inability to understand her fabricated dialect, she hastily paces back and forth while pointing at the artwork with a long red stick. Shown side by side, these two works behave as an anchor for the sprawling, wide-ranging exhibition. UnMYthU and Alexa open our eyes to the ways in which Eurocentric language shapes our social, artistic, technological and political environments, revealing the long and complex relationship between vernacular, colonialism and migration.

mOTHERTONGUE at Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 22 April – 18 June