Auriea Harvey, Norma Xelda Jara, Sarah Friend and Mario Klingemann are expanding the possibilities of digital art in the era of the nonfungible token

It’s been a year since The First 5,000 Days, by Mike Winkelmann (aka Beeple), sold at auction for the cryptocurrency equivalent of $69 million, making it the most expensive artwork by a living artist sold at auction. But more importantly, it was an NFT – an artwork sold as a ‘nonfungible token’ – and its sale brought the growing craze for NFTs to widespread public attention.

A year of hype has ensued, with many in the artworld keen to jump on the bandwagon of these blockchain-based virtual rarities, while detractors have criticised NFTs and blockchain technologies for being everything from a vast Ponzi scheme, to a threat to the environment, to the cultural expression of the misogyny and racism of ‘white tech bros’.

But outside the hype and controversy, the growing popularity of NFT platforms and techniques has transformed the way artists of all kinds can create a market for their work. Whether these are digital artists who have been working with blockchain or artificial intelligence, or ‘traditional’ artists who have brought physical artmaking into contact with virtual online contexts, the NFT boom has opened new channels to audiences, collectors and markets. To explore some of the work that doesn’t fit the hype, ArtReview asked four artists, digital curators and critics to profile artists whose work explores the potentials and possibilities of digital art in the era of the NFT…

Auriea Harvey

by Charlotte Kent

NFTs bring attention to digital art and those artists, like Auriea Harvey, who have been innovating with emergent technologies these past 25 years. Harvey is recognised as OG in the NFT community for her long-standing digital and game-art practice. Trained at New York’s Parsons School of Design, she mastered the careful modelling of 3D characters in her subsequent career designing indie games. Harvey is truly post-medium: digital and analogue are two sides of the same art practice.

She first heard about blockchain from Ruth Catlow, artist and co-director of London gallery Furtherfield, and made her first NFT in 2019 with a2p, an artist-to-artist blockchain initiative of generative artist Casey Reas that preceded Feral File, an important blockchain gallery that Reas launched in April 2021, and where Harvey has also shown. Her historical work in net art and participation in Hic et Nunc, among other artist-led NFT communities, made her a key figure in the 2021 NFT boom. This occurred simultaneously to her solo exhibition in March 2021 at New York’s Bitforms Gallery, Year Zero, in which she presented sculpture and prints appropriating and reimagining Hellenistic mythic figures, some of them renditions of the statuary surrounding her daily life in Rome; accompanying NFTs dropped shortly thereafter.

The marblelike bust of Minoriea (2018), shown at Bitforms, exemplifies the iterative complexity of Harvey’s travels across the virtual and tangible. She extracted the figure from her VR experience Minorinth (2017) – itself based on the merging of her own features with that of a minotaur – and produced the physical bust as she started experimenting with 3D printing. The NFTs of Minoriea operate as a means of representing a complex package of archival and interactive files that the collector receives. From the 3D model, she made browser-based artworks that have an AR component. Blockchain platforms have different visual allowances, so Harvey’s environments for Minoriea depend on context. Each NFT is a new space in which Minoriea circulates. First introduced as an NFT in April 2021 when Bitforms launched the NFT site bit.art, Minoriea appeared a month later in Christie’s first NFT auction, Proof of Sovereignty.

Later that year during Art Basel Miami she released The Adventures of Minoriea, four lifesize AR animations expressing a mood, activity or state, among them Minoriea is Dancing and Minoriea is Drunk. These NFTs were limited editions of five. Her play with self-portraiture is generative, with renditions unfolding across new developments and platforms. Her appropriation of classical mythology for these NFTs invokes a liminal realm, where fantastic archetypes represent real, psychic impact. It speaks to our own hybrid moment negotiating the virtual and tangible. Despite some of the ethical and political ambiguities that critics attach to NFTs, they have made computer and code-based art more prominent and enabled digital and analogue work like Harvey’s to be seen as equally complex practices.

Charlotte Kent is an assistant professor of visual culture at Montclair State University (NJ) and an arts writer

Norma Xelda Jara

by Jason R. Bailey

Crypto-art culture was born out of the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2009 invention of bitcoin. Shellshocked by the fragility of a centralised monetary system, a movement emerged for the exploration of decentralised alternatives. Attempts to disintermediate banking inspired artists to attempt the same in the artworld. There was plenty of incentive, as many artists felt the traditional art market either did not serve their best interests or ignored them altogether. One such artist is Norma Xelda Jara.

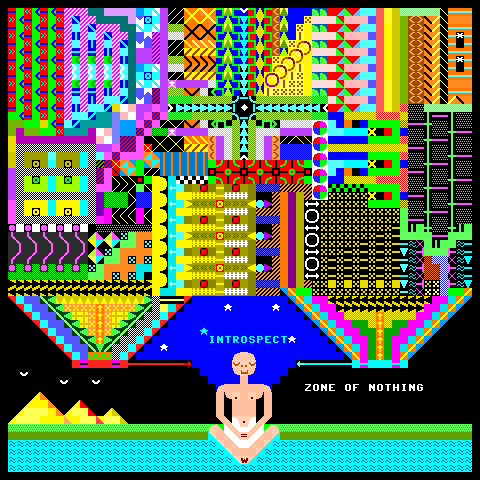

In a highrise apartment in Buenos Aires, Jara, a chain-smoking grandmother unafraid to speak her mind, has crafted a series of brilliant animated gifs – pixel-art masterpieces that perfectly capture the zeitgeist of crypto art and NFTs. These tapestrylike animations interlace brightly coloured icons, glyphs and text within a matrix of pixelated tracery. They are flat, decorative and deploy highly stylised imagery. The works are allegorical but read as a cross between a Sunday comic strip, a mid-1980s PC game and an ancient Mixtec codex.

In Jara’s 2021 Cryptodrama frenetic blinking phrases warn us that the cryptocurrencies tezos, ethereum and bitcoin are either ‘down’ or ‘dead’. The word ‘scam’ is woven into its design, and three pyramids sit in the lower left of the frame, symbolising the common criticism that NFTs are a thinly veiled Ponzi scheme. Juxtaposed against this negative signalling are words like ‘community’, ‘life’ and ‘interest’. Amid the noise sits the serene figure of an artist, perhaps Jara herself, summoning universal energy through introspective meditation. Or perhaps the figure isn’t Jara, but rather a distillation of all artists trying to enjoy the opportunity of a runaway market without getting run over themselves.

There is a long history of great artists capturing and reflecting the world they live in using the tools of their time. Few have captured the anxiety, FOMO and uncertainty of 2021’s manic crypto-art craze as pointedly as Jara. Living in Argentina’s fragile, inflation-wracked economy, far from the geographical centrefold of the artworld, Jara has worked out that NFTs give her a shot at generating income from her art. She may not become the next Beeple, but NFTs have changed who gets to participate by giving Jara and thousands of other artists globally a stage and a new class of patrons. These are patrons with different baggage from those of the traditional artworld; patrons willing to support, or at least take a chance on, previously marginalised artists like Jara.

Jason Bailey is a curator of digital art and the founder of the art and tech websites artnome.com and rightclicksave.com

Sarah Friend

by Rhea Myers

Artists’ engagement with blockchain technology predates the first NFT, which is generally regarded as new-media artist Kevin McCoy’s Quantum (2014), a digital image with its ownership registered using the Namecoin blockchain. Blockchain art started out as a critical engagement with the hardware, software and culture of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. These early blockchain artists drew on the precedents of conceptual art, net art and other moments of uncertainty in the property regime of art to draw attention to environmental impacts, financialisation and the creation of new kinds of property.

But it was not until the start of 2021, with the $69 million sale of the first NFT released by artist Beeple (Mike Winkelmann), that a much wider audience became aware of NFTs. That audience has been almost universally hostile.

That’s a shame, because NFTs have brought attention, community and much-needed revenue to a wide range of artists who don’t fit the planet-destroying, ‘crypto bro’ stereotype that draws such hostility. From infectiously enthusiastic young artists like FEWOCiOUS (Victor Langlois) to important but marginalised figures in the history of glitch art such as Dawnia Darkstone, NFTs are bringing new artists and audiences together. Alongside these developments, through boom and bust and boom again, early blockchain artists have maintained their critical engagement with the technology and its newly popular expression as tokens.

Sarah Friend is one such artist. Her ClickMine (2017) focused on the environmental impact, economics and possible sources of technological failure of the blockchain by requiring the player to engage in a ‘clicker’-style game in order to claim ethereum fungible tokens, which turn out to be hyperinflationary as the game progresses. Lifeforms (2021), her latest project, disrupts the cryptographically secured ‘true digital ownership’ of digital art and the economic rationality of investing in NFTs that their proponents tout. Lifeforms creates colourful, hypnotic, code-art organisms that you must give away within 90 days of receiving them. The ‘smart contract’ blockchain program that registers the ownership of each Lifeforms NFT also registers the date when each is transferred and refuses to list it in your blockchain wallet or to transfer them away from it if too much time has passed. This means that if you try to hold on to them any longer they ‘die’ and disappear from your collection permanently, and cannot be revived elsewhere. Yet if you do give them away, they will no longer dance engagingly on your screen for you.

Lifeforms is a finely tuned experience that uses visual appeal and the psychology of gamification to pit social care and the circulation of gifts against the economic imperatives of ownership and profit. We value the work because it is beautiful, and we come to care for it, but if we care for it, we have to let it go and we thereby lose possession of that value in order to ensure its continued existence in the world. The affective and material tensions that Lifeforms translates into rhythms of satisfaction and loss bring the contemporary financial imaginary into focus for contemplation. In doing so it demonstrates the lasting critical (and dare I say aesthetic?) value of artists working with the still-new technology of the blockchain and NFTs as their chosen medium overtime.

Rhea Myers is an artist, hacker and writer. Her work places technology and culture in mutual interrogation to produce new ways of seeing the world

Mario Klingemann

by Eric Drass

One of the unexpected results of the NFT boom has been the surge of interest in generative art and, in particular, AI-generated imagery. Generative art has been around for decades; art created by following a programmatic system of instructions, often performed by a computer – the role of the artist becomes ‘configurator’, and sometimes ‘curator’ of the outputs of these systems. By definition, generative systems can potentially produce an infinite number of images that are ‘variations on a theme’. Sometimes the generative systems themselves are offered as NFTs, allowing the collector to enjoy the variations produced. More frequently, the artist acts as curator, selecting (and perhaps manipulating) specific results. The NFT ecosystem, being inherently ‘digital first’, has provided a place for these (hitherto somewhat arcane and marginalised) forms of art to flourish.

The relationship between artistic intent and the output of AI systems is often loose. The results may be unexpected, yet the automated nature of production means the artist can be presented with hundreds of variations before selecting ‘the best’. Often the influence of the human artist over the form of the output is minimal. But if this is ‘art made by computers’ with minimal human intervention, where precisely does this leave the role of the artist?

To address this conundrum head-on, German digital artist Mario Klingemann created Botto (app.botto.com), an automated artmaking-machine that creates 3,000 images each week, which are passed to an internal AI judge, which selects 350 of them. The images themselves are woozy, lysergic, semiabstract forms, sometimes referencing the styles of notable human artists into the mix.

These 350 weekly images are then voted upon by the community of people who hold Botto’s native cryptocurrency, botto. The votes of this decentralised group of real humans – whose collective decision-making guides the direction and taste of the underlying system – lead to one winning image that is then minted as an NFT. The attributes of the winning work are used to guide the style of future works, and to finetune the system’s ‘taste’. There is no one single artist, or even collective, with agency over the work, nor does the community have any tangible control here – the ‘taste’ of Botto is driven by the democratic decisions of the audience. The profits made by the NFT sales are used to buy up and destroy the botto currency, hence increasing the value of the voting stock. Because of the automated ‘smart contracts’ of the blockchain, all of this happens without the need for an agent, gallerist or any other percentage-scraping art-market intervention. At the time of writing, Botto has made a total of $1,846,529 from the first 17 sales.

The traditional artworld has long argued over the relationship between artist and production. It feels important that the aura of the artist is carried through to the resulting work, and conversely we like to be able to point to the human intent and agency behind it. Whether Goya’s paintbrush ever touched The Colossus (after 1808) feels significant, but do the works produced by Botto differ fundamentally from one of Damien Hirst’s spot paintings lovingly executed by his studio assistants? As the associated manifesto states: ‘We create our creators. We do not follow the crowd because we are the crowd. The idea of we is an illusion.’ Tellingly, the manifesto itself was cowritten by AI…

Eric Drass (aka shardcore) is an artist making work at the interface of humans and AI. His most recent project can be found at themachinegaze.com