The artist’s new exhibition at ICA London asks what has – and will – become of language in the age of the Large Language Model

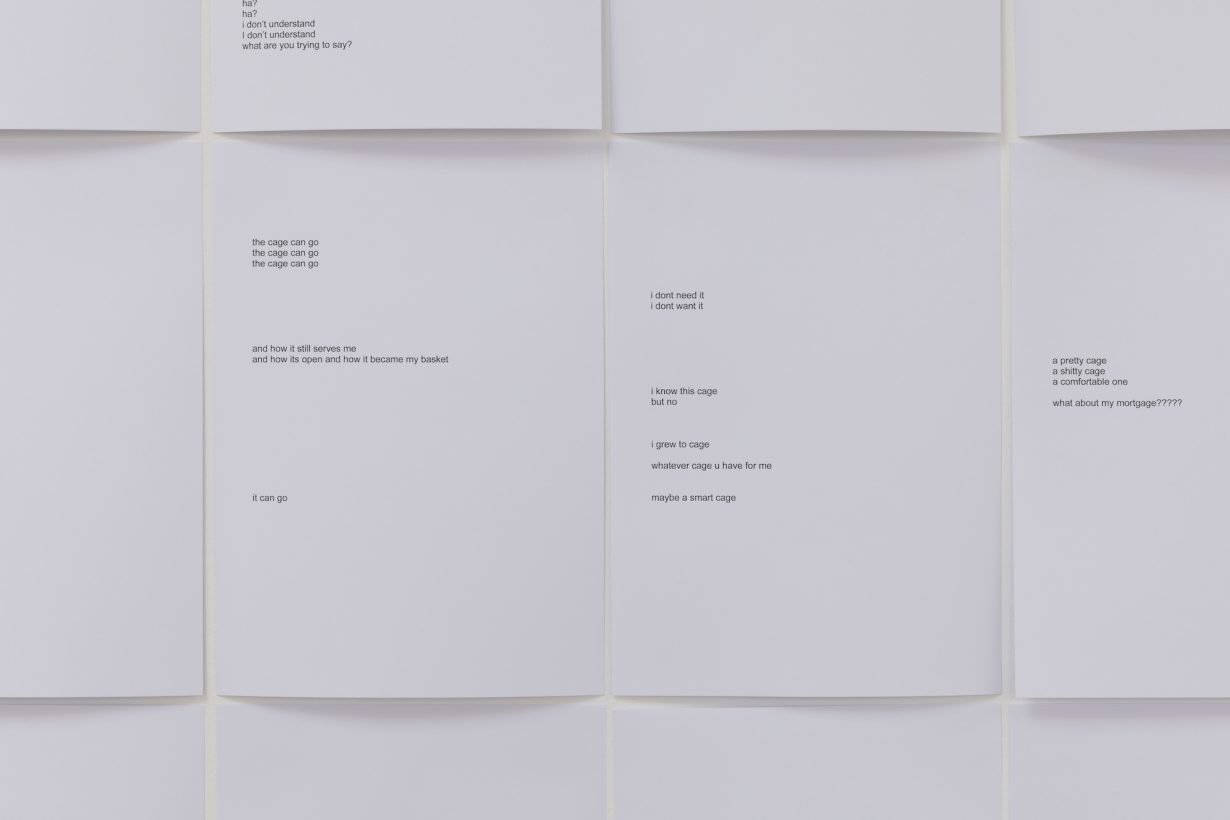

Nora Turato’s first UK solo show pool7, the latest iteration in a series that began in 2017, fills the primary exhibition space walls of London’s ICA with some 1,800 A4 printouts. Only a few lines of text occupy each page but with so many to read, you can’t help but scan inconsistently; up, down, diagonal, left, right. The texts muse over everything from pelvic-pain, TikTok, hive-mind, to the nature of being in an ovulating body in an online world – it’s like entering a brain with a flitting attention span (though she is anxiously conscious of that); the thoughts of a thirty-something woman making art even though there is already ‘enough content out there’, she writes on one sheet. So then, Turato determines, just keep at those jaw exercises, eat, digest, shit, write more words and dance to Madonna. In a darkened annex room, a pre-recorded fifteen-minute monologue is littered with shifting vocal registers and guttural reflexes. And on the gallery’s outer walls, mute videos of Turato doing what look like vocal warm ups evidence the physicality of generating words and sound.

Turato’s earlier six pools featured found text (wellness mantras, press releases, food labels, viral memes and screenshots of conversations) which she would collect, then cut up, rearrange and consolidate in published volumes. Fragments of text also appeared both as wall paintings and enamel panels, and, woven into a script and safely memorised, informed a series of spoken-word performances. In collecting and repurposing text-based media from the past six years, the pool series reveals how meanings mutate, and linguistic trends – in branding, pop-songs and social-media – slide into everyday parlance. This time pool7 even looks like a report. Forgoing the series’ earlier bulky tomes and sprawling murals in bright colours and custom typeface, Turato opts instead for the standardised simplicity of a blank Word doc. In a sense, the document’s visual efficiency suits today’s drive for ‘frictionless’ communication. The unfiltered immediate transfer of thought-to-language, replete with online shorthand, epitomises what we might call ‘brain dump’ – a phrase generally attributed to productivity guru David Allen in his ‘Getting Things Done®’ ‘work-life management system’; no doubt a riff on ‘core dump’, a term used in early computing to describe paper printouts of a computer’s ‘memory’ arranged in lines for post-mortem analysis after a system crash (not dissimilar from pool7, then).

Moving away from found text, the words in pool7 are (almost) all Turato’s: ‘I am 33 years old and i’ve found the words i’ve been looking for,’ states one text. Turato’s mother-tongue is Croatian and she’s described learning English as using ‘other people’s words’. But – after consuming all those wellness mantras – is she finally ‘speaking her truth’? Authorial paranoia seeps through: ‘I fill the words / it’s me who fills them / I don’t need to be filled with words’. She writes of ‘devouring’, ‘digesting’ and ‘gagging’ on language. In the recorded monologue, between gags and splutters, Turato exclaims: “I drowned in words / Words were not mine / The words I ate / All those fucking words”. Absolute authorship isn’t immaculate – recall Joan Didion religiously typing Hemingway sentences to hone her ‘style’ – and Turato, conscious of external influence and dubious of how ‘authenticity’ can become doublespeak, is testing out what her voice is. But she doesn’t sound entirely convinced.

Questions of style and authorship are further troubled by the prevalence of Large Language Models (LLMs) and their corrosion of linguistic diversity as we understand it. Between 2021 and 2024, for example, the words ‘delve’, ‘underscore’, ‘meticulous’ and ‘commendable’ started appearing with unprecedented frequency in scientific journals. This coincided with the launch of OpenAI’s Chat GPT, and Florida-State researchers identified a further 21 ‘lexical items’ – not new terminology, but stylistic preferences – ‘overused by ChatGPT in scientific writing’. In late 2024, Researchers at the Max-Planck institute found AI word-preferences are now influencing spontaneous spoken language, like microplastics in the brain. Every innovation brings new lexicon to vernacular language.

In pool7, four words are listed on one page: ‘Mobility. Longevity. Transparency. Community.’ The combination of terms recalls their insidious appropriation as corporate values, the legacy of an earlier language shift when, in the 1950s, the nascent field of ‘Organisational Management’ drew Taylorist principles of machine efficiency into corporate communications. That was the work of mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor who in 1911 published a book on scientific management that conceived human labour in terms of machines, spawning a whole new world of figurative jargon. Now, office workers ‘run out of steam’ and bemoan a lack of ‘bandwidth’. At the bottom of the page with those four words, Turato perceptively states: “Being human is so exhausting it’s why we stopped being human”.

A new book, Flower by the artist Ed Atkins, similarly tests the confessional mode’s authorial ‘authenticity’, combining everyday observations with digressions into fantasy. In the opening pages Atkins describes the perverse pleasure of eating a pharmacy sandwich wrap: ‘The main ingredient in ultra-processed meats is their ultra-processing, the ultra-processing culture and its technologies and histories rather than the beautiful pig in the past’. Much, indeed, like words churned through corporate machines until lifeless. After eating, Atkins drifts into the fantastical, describing himself as ‘a basic model cyborg on the streets with bits dangling off’. You are what you eat.

Food proves a helpful lens onto language; anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss observed that ‘there is no human society which lacks a spoken language so also there is no human society which does not, in one way or another, process some of its food supply by cooking’. In Levi-Strauss’s culinary triangle, cooked food is raw food that has been transformed by a cultural process, and such processes can be revelatory of structures of thought and language. Today, our food is not just cooked but extruded, molded, hydrolysed and hydrogenated, what then does that mean for our language? LLMs, unable to digest raw text, tokenise or ‘chunk’ words into numeric ‘identifiers’, to then predict subsequent identifiers. The reading sensation is one of consuming something premasticated. No wonder then, as Atkins mischievously states, ‘the best writing is people writing a synopsis of a ridiculous horror or sci-fi film online’ which is then ‘affectlessly read… over a supercut of the film’. Signs get blended into simulacrum, unmoored from their meaning.

All this ultra-processing gives rise to a quandary: it was our language training and our feedback that created the vocabularies of the bots. When did the tables turn? What remains of that beautiful pig in the past? AI responses now commonly include AI-generated content: AIs converse with other AIs, LLM-generated content is fed into the training of new ones, and humans engage one AI to write the prompts for another. In 2023, tech reporter Casey Newton raised ‘serious concerns about the gradual dilution of the “human factor” in… text data’. It has all gotten rather ouroboric: who is eating who?

‘How do we take language back and start using it consciously, instead of letting it consume us?’ Turato asked in a recent interview with Émergent magazine. Throughout pool7, you can feel her grasping for a semblance of ‘the real thing’. I’m reminded of when Edward Bernays, a pioneer of PR, was appointed by Betty Crocker, whose instant ‘just add water’ cake mix was not selling well. Drawing upon the theories of his uncle Sigmund Freud, Bernays suggested that the mix require the user to add an egg, thus making them feel like they had some agency. It was an instant hit. I can’t help but think prompting LLMs is a little like adding that egg.

So how does Turato stave off her consumption by language? In the recording she pronounces: “I’m not a body machine” before recognising “I was on my way to becoming one” – much of the writing in the show is caught in that limbo. She has however previously seen a voice coach, and one note references the Soprano Carol Neblett’s advice: ‘A woman sings with her ovaries – you’re only as good as your hormones. Loosening her jaw, opening her throat, working ‘from the gut up’ and breathing into her pelvis, Turato is taking language back into the body.

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer