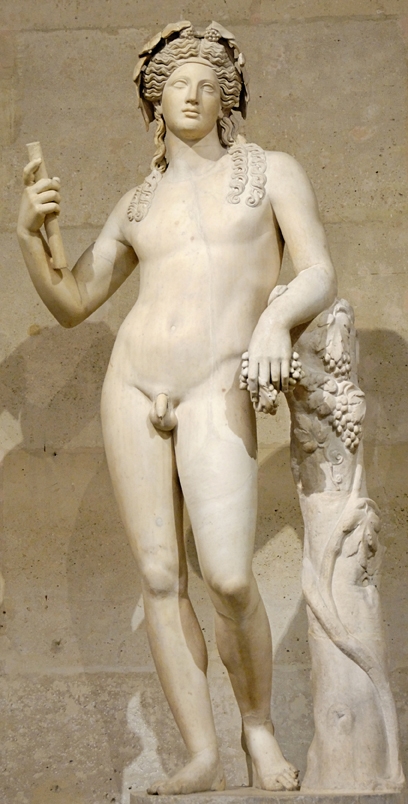

Worship of Dionysus is thought to go back at least to the seventh century BC. The deity is known as the giver of joy and associated with intoxication, in particular the drinking of wine, as well as with nature, vegetal growth and animals. In aesthetics, following Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy (1872), the term ‘Dionysian’ refers to the side of creation associated with feeling and intuition, as opposed to reason and clarity.

ARTREVIEW

Hi, it’s great to meet you. There’s been a lot of publicity in London recently about powerful performances by actors playing strong female roles in Greek classics like Euripides’s Medea and Sophocles’s Electra.

DIONYSUS

Yes, unfortunately there is no equivalent role in the play that focuses directly on myself, The Bacchae. On the other hand it is certainly a warning of the danger of an out-ofcontrol femininity. With that work Euripides was acting as the mouthpiece for the Athenian masculine order, warning against the spread of my rites. Although these were always held in secret, and to this day their content remains an enigma, it was understood that women were attracted to them. The norm was that women’s activities were confined to the domestic context. What could they be up to, dancing and drinking in the dark, along with men dressed as women? These sensational matters are spoken of in an early scene in The Bacchae, in an exchange between Pentheus, the doomed king, and myself. At the conclusion of the play Pentheus is torn apart by my maenads, whose name literally translates as ‘raving ones’.

Yes, what’s all this tearing apart about?

D ‘Dionysus’ is an evolving symbol. All sorts of concepts are made to fit it. It is undying. For example, today the international art audience is conditioned, for better or worse, to believe that Carolee Schneemann’s performance Interior Scroll, from 1975, the heyday of the first wave of feminist art, represents a summit of emancipatory expression. Naked and besmeared, she draws a text from her own body. Inch by inch, legs splayed in an awkward standing position, out it comes. Maybe there’s a suggestion of the tearing that occurs during birth. What is being born is the ability to speak. It is a modern initiation. She reads the scroll as it emerges, to an invited audience of mostly women artists. It bears the transcript of a conversation between herself and a structuralist filmmaker colleague, in which Schneemann sets intuition and bodily processes, traditionally associated with women, against traditionally male notions of order and rationality. Moments earlier she declaimed another self-written text, with only an apron veiling her nudity. In that case it was some lines from a book she had just written: Cézanne, She Was a Great Painter. Then she cast off the apron and started pulling out the scroll.

Ha ha, the chaos, man – I love it.

D Perhaps it is me you love. The Dionysian always relates to the body. To the ineffable, the unsayable and the shadowed. The animal. The figure of Dionysus, myself, as it is represented in art is never unambiguously male. Its womanliness is inescapable.

I guess. How about another drink?

D Thank you. In fact the cult is all about interpenetration of formerly distinct identities. The Greeks had their famous slogan at the Delphic oracle: ‘Know thyself’. But participation in my rites entailed precisely the opposite: loss of self. Man becomes woman. Woman acts against the rule of man. What is torn? A body. What body? Animal sacrifice was part of the natural order for the Greeks. But the initiates of my cult turned this regular practice on its head when they met secretly in darkness, and tore apart animals or human beings and devoured their raw flesh. Such devouring is called omophagia, while the tearing apart is the sparagmos. In some myths I inflict suffering and death, while in others I myself suffer and am torn apart but then return to bring new life.

I’m looking up Griselda Pollock on Google. I’m sure woman-as-nature is a major faux pas.

D She tells her readers that feminism is not just the study of women or gender; it is the politicisation of issues of sexual difference as sexual oppression in all the categories of its historical and geopolitical specificity. The promise of feminism’s political project is to address people across profound and obscene social divisions by calling to ‘women’, by naming as oppression the othering of the feminine and feminisation as a means of othering.

Is that everything she says?

D No, it’s more like something she says at one point in an explanation of Julia Kristeva. The phallocentric social order is predicated on sacrifice: giving up the archaic fantasy of unity or achieved identity in order to accede to language, sexuality and sociality. Humanity’s sacrifice of its imagined wholeness, its archaic corporeality, to the Symbolic, to language and to representation, is experienced as violent: this is the allegorical meaning of ‘castration’ – the only contract the phallocentric order knows. In my rites, of course, the violence is all in the other direction. Nonindividuation is affirmed. To shift to the language of transcendence, everything is the same divine thing, divinely created. If thought exists in individuals, then thought must be part of the cosmic principle from which they themselves came. There exists therefore a universal thought, a universal self-consciousness, and thus creation is not simply a chance matter, but the choice of a transcendent will which caused it to be as it is.

I realise I’m confused by two sets of ideas featuring big dicks, whose difference I never thought about before. For feminism the phallocentric is women ruled by men. For ancient religions, worshipping a phallus affirms everyone’s rule by nature.

D Hmm, yes, for you, rather than a dialectical tension, which could be fruitful, there is just an annoying clash of phalloi metaphors. I should say that Hélène Cixous’s term, phallocentrism, doesn’t of course refer to historic rural agricultural festivals in the early spring, usually including a procession called the phallophoria, in which participants bore phallic images or hauled them on carts. Rather, it means patriarchy. It is drawn from Derrida’s logocentrism, meaning a kind of thought characterised by binary opposites.

What exactly is your cult?

D I unleash the powers of soul and body in those that worship me. My rites are profoundly antisocial, a religion of nature that opposes the religion of the cities, which is anthropocentric. I represent the stage where man is in communion with savage life, with the beasts. I’m a god of vegetation, of the trees and of the vine, and I’m an animal god, a bull god. I teach man to disregard human laws and rediscover divine laws. I represent disobedience. In India today remnants of my ritual can be found in Shivaism. The ancient legend that India was temporarily my home is an allusion to the identification of my cult with the cult of Shiva. We are the same: East to West.

Why all the drinking?

D There has to be dissolution.

The life of the worshipper that enters into my mysteries is renewed, culminating in the eating of the raw flesh of the animal that is myself made manifest, the bull, whose blood also sanctified my shrines

What would happen if I were initiated?

D The initiated mystic learns that I die but I am reborn. The life of the worshipper that enters into my mysteries is renewed, culminating in the eating of the raw flesh of the animal that is myself made manifest, the bull, whose blood also sanctified my shrines. By the way, 1975, the year of Interior Scroll, is also the year of publication of Cixous’s essay ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’. It was men that created the Medusa, she writes, the hideous female whose countenance causes death to any man that sees it. The Medusa is men’s fear of women, Cixous asserts. But, she says, ‘She is not deadly, she’s beautiful, and she’s laughing!’ The essay is a call to all women to find a voice, to write, to speak, to resist. When she writes in the same essay that women generally should listen to the woman ‘who speaks’, once fear is overcome, the image conjured up, in its explosive unembarrassed emotionalism, might be the Schneemann performance itself. ‘She throws her trembling body forward; she lets go of herself, she flies; all of her passes into her voice, and it’s with her body that she vitally supports the “logic” of her speech. Her flesh speaks true.’

Do you think Phyllida Barlow is a maenad?

D There’s nothing frenzied about Barlow. In her art she obeys a modernist play-of-materials tradition, which is both sculptural and painterly. She is very successful in the aesthetic surprise that she brings to it.

She’s a great woman artist who only wasn’t successful before because of prejudice, but now she’s getting her rightful due, and it’s the success of people like Carolee Schneemann that made that possible.

D Certainly feminism has created a climate in which her achievement can be brought to a wider audience. By the same token, critical reception of it can be unreliable. She is concerned with structure and process, but there was something unconvincing precisely on a structural level about her recent Tate Britain commission. Large objects were produced to occupy the Duveen Galleries. In my view, the way the parts were put together often referred to a constructive tradition while actually not being that, but being decorative instead. And the critical response to the show didn’t have the subtlety to register that distinction. It was too preordained: a woman artist must be applauded.

Why analyse in that pedantic way? Criticism today is for making sure your position in the professional power structure is OK. As critics we say what everybody else says, not something that we only think ourselves.

D Her work is complex and rich, usually, so when I observed a lack of richness I found it disappointing. An exception was a columnlike sculpture made of flimsy materials. This was convincing as aesthetic experience, which, after all, is the basis of what she does. The cardboard was allowed to buckle and flare, the tape tying it up had nice colours, it had an appearance of absolute easiness, but its genuine structural logic could only have come from quite a lot of thought in the past about materials.

So to sum up, phallus worship is to take one’s place in the cycle of birth, death and renewal: the eternal round?

D Yes, it’s my round.

Cheers, mate.

This article was first published in the November 2014 issue.