Sabelo Mlangeni’s No Problem

Do you love me Alexandra, or what are you doing to me? (1)

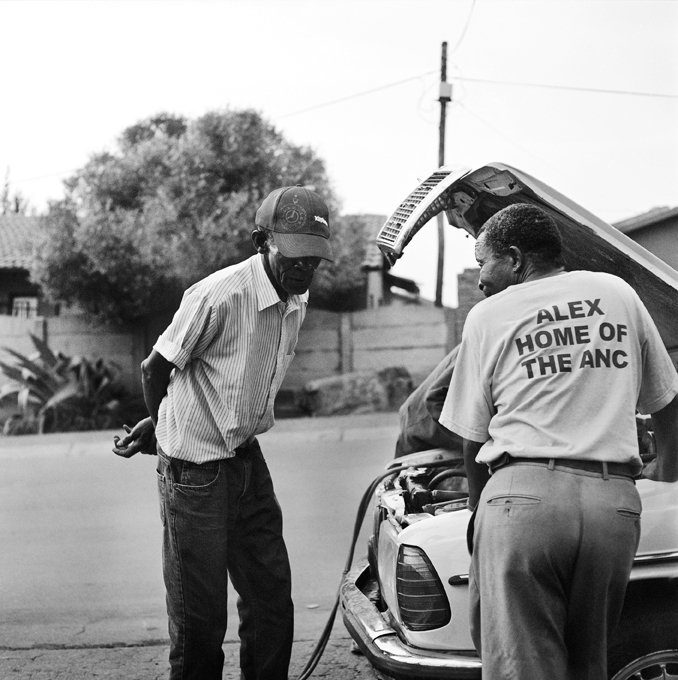

For three years Sabelo Mlangeni lived in Alexandra, Johannesburg, during which time he began his photographic series No Problem (2011–3). Alexandra, or ‘Alex’ for short, is known and often described as an urban problem ‘too close’ in location to Sandton, a wealthy suburb. In his 1972 poem ‘Alexandra’, Mongane Wally Serote likens this township to a mother whose breasts ooze dirty waters diluted with blood. Often, Serote’s story of Alex is narrated with a mixture of repulsion and attraction, characteristics that pull and push each other, without ever snapping:

I have gone from you, many times,

I come back.

Alexandra, I love you;

I know

Mlangeni’s No Problem is a body of work in search of an ordinary image. Seen in its totality, the series appears to be a very personal portrait, not necessarily of a place, but an individual straying and becoming familiar with a place historically known, experienced and monumentalised in literary and popular cultures by millions since its founding in 1912. [Alexandra was founded a year before the passing of the Native Land Act of 1913. It was proclaimed a ‘Native Township’ and is one of the few urban areas where black Africans could own land under a freehold title.]

Every now and then, Mlangeni strays outside the borders of Alex and enters Sandton. At this point the picture is delivered in colour; it is perhaps the first time Mlangeni photographs in colour. His Sandton however is far from colourful. The two neighbourhoods are spilling into each other in minute details, where one cuts from the other and pastes to their own. The ‘cut up’ features are less about affluence entering Alex or poverty infiltrating Sandton. It is the flow of historical time and space and the place of objects within a larger continuum, a future leaking out. Serote again:

When all these worlds became funny to me

I silently waded back to you

And amid the rubble I lay,

Simple and black.

Sabelo Mlangeni was born in Driefontein near Wakkerstroom in Mpumalanga. He moved to Johannesburg in 2001, where he joined the Market Photo Workshop, a pioneering photography school, studio and project space that has played a formative role in the career of artists such as Zanele Muholi. Since Mlangeni’s graduation, in 2004, his work has been the subject of solo exhibitions in South Africa and the US, and has been exhibited in major international shows including the Lubumbashi Biennale (2013), the Liverpool Biennial (2012) and Public Intimacy: Art and Social Life in South Africa, at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco (2014). The 2009 recipient of the Tollman Award for the Visual Arts, he has published three books, Men Only (2009), Country Girls (2010) and At Home/Ghost Towns (2011), which focus, respectively on a hostel for male migrant workers in Johannesburg, gay communities in the rural districts of his home province and small towns in South Africa that have either been half-emptied by migration or abandoned altogether as the country transforms.

(1) Mongane Wally Serote, ‘Alexandra’, in Yakhal’inkomo: Poems (1972)

The horse tooth and the kudu horn: A visit to the site of Michelle Monareng’s Removal to Radium

It is the morning of Saturday 14 December 2013. Nelson Mandela was declared dead nine days ago. Tomorrow he will be laid to rest in his homeland Qunu in the Eastern Cape province. Kenneth Kaunda has arrived for the funeral. Last night the Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR) staged a small event titled The 2nd Coming in our office at the Wits School of Arts. The event was planned before Mandela’s death; it is not his second coming we were anticipating. The 2nd Coming happened a year to the day after we staged our own institutional death with the event We are absolutely ending this. Last night was in fact a launch of a website that, up to this day, refuses to come to life. Our new well-articulated tongue-in-cheek logo was ready. We stuck it over a beer bottle label, obliterating the beer’s recognisable association with blackness. The logo resembles logos of other official institutions but instead of an eagle or a kudu, on our shield stands a pink elephant – for the future of our intoxicated memories. Grey is the colour of history; pink is the future. There are seven stars in white and the acronym CHR is in black and grey.

People came and crowded the small office. We ate and we drank. Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) played on a LG (‘Life’s Good’) TV monitor. No one was really watching. Our intern was there still trying to fix the website. The story of the fake sign language interpreter at Mandela’s memorial is dominating the conversations. There is laughter and disbelief. We are at the centre of the world yet again. Even Slavoj Žižek will write a commentary about the sign language interpreter, dull but written nonetheless. A recording of a performance from 2012 is playing on a computer monitor. It is a scripted but silent dialogue set in the future. Two sets of hands discuss the ever-anticipated death of Mandela, which never happens. In 2081 Mandela is a twenty-five-year-old man and long unremembered. Instead of dying in 2012 he became younger each year. Our head of department gives us a gift of a small woven carpet with the portrait of Chris Hani (leader of the SA Communist party, 1991–3). We hang it on our notice board. A mask of Margaret Thatcher is also there.

We are driving, five of us in one car, all women. Michelle Monareng is directing; we are headed to her ancestral land one hour out of Johannesburg. We reach the district of Heidelberg just before lunch. On reaching the Suikerbosrand River, Monareng instructs us to stop the car and report our arrival by throwing a few coins in the river. We are to do the same when we leave tomorrow. Mandela’s body would be six feet under but his spirit and image will haunt for longer, forever. We drive towards Rietspruit Farm no. 417 I.R. and arrive on a plot of land with built property: houses, a hall, a warehouse and an empty swimming pool. We are welcomed by Monareng’s relatives, who hug us warmly, and their dogs, who bark, jump around, smell and lick, and then quickly get bored.

Led by Monareng, we gather our cameras and other recording equipment and begin to walk. We reach a pond. There’s a skull of a dead horse. I pull a tooth out of it and start polishing it with a stone. The tooth endows me with special powers. We have fun skipping stones onto the dam. There are more skulls of dead animals, cows, kudus and… The feeling of walking through Monareng’s artwork, recognising where certain images were made, is both exhilarating and unsettling. Eventually we reach the spot where her video Removal to Radium (2013) was shot. She stands at the exact spot where she placed her camera and narrates how it happened.

‘Haunting’ is the appropriate word to describe the video; after all, it was shot on haunted land. The landscape appears empty save for some houses; we will sleep in one of them tonight. There are other houses and buildings in ruins; an old deserted church building, a house built by the Berlin Missionaries, a mission school, scattered and unmarked graves, a small graveyard for white people (marked) and another for black people, where Monareng’s grandfather Sonnyboy Abram Shikwane rests. Shikwane’s battle for the return of the land is documented in an extensive archive generated as evidence submitted to the Land Claims court in 1995.

Farm no. 417 I.R. is one of many places whose story of forced removals does not feature in the official narrative of our history. Were it not for Monareng’s ongoing research project, also titled Removal to Radium, we would still be ignorant, not only of the history of this place but of all other historical blind spots… Were it not for her grandfather’s obsessive documentation and collection of materials, the archive would not exist.

Shot in black and white on a misty spring morning, this less-than-two-minute-long video captures a fragment of a legend known to some community members who remain haunted by the 1965 forced removal from their fertile farmland. In the video, a man, Monareng’s uncle, is seen digging in front of a sand mound almost his shoulder height, suggesting that the digging has been going on outside of the frame for some time. He is suddenly confronted by a handful of cows and their murrring sounds. Taken aback, the man stops momentarily and then continues to dig as the herd strolls in the foggy background. One bull cow approaches and lingers very close behind the growing mound, inspecting the digging activity.

It is rumoured that those who have tried to retrieve the money buried with the farmworkers would, during the act of digging, start to hallucinate. It is said they would start to see a wild animal, usually a lion, and lose normal perception for the remainder of their lives

The video is shot on the piece of land from which the community of Rietspruit Farm no. 417 I.R. was forcibly removed to make space for white farming. They were moved to Radium, a barren land where nothing grew. The extent of the trauma experienced by the people of Rietspruit (Tswinyane is the local name) is told through archival materials gathered over a period of 20 years by Shikwane. In a timeline dating from 1837, the year Rev Alexander Merensky was born in Germany, the story of dispossession is summarised. Shikwane also notes that in 1965 ‘some people died because of climatic changes. Radium was too small for the community (⅕ of the original land of removal).’ Now a custodian of her grandfather’s archive, Monareng has been studying it: documents, video testimonies, photographs and timelines, and creating work that stands as counterarchival responses to the collection. The video, however, is a result of interviews the artist conducted with community members in which a story not documented by her grandfather starts to emerge. People told of how Botha, the farmer who took over from the Berlin Mission, would walk around the land with a black farmworker carrying a sack full of money. He would then ask them to dig a hole big enough to fit an adult human after which he would ask the worker if he would guard the money with his own life. At the confirmation of this, he would then throw the worker in the hole, shoot and bury him with the sack.

This may explain the unmarked graves scattered around the land. It is also rumoured that those who have tried to retrieve the money buried with the farmworkers would, during the act of digging, start to hallucinate. It is said they would start to see a wild animal, usually a lion, and lose normal perception for the remainder of their lives. This story, which sits somewhere between contemporary legend and historical fact, sums up the absurdity of the oppressive regime of apartheid and its laws. Many more narratives are yet to be uncovered, and a lot more will forever remain buried in history’s shallow graves. Monareng’s ongoing research project aims to uncover and ‘imagine the production of a different kind of knowledge and historical narrative’.

That evening we experience a violent thunderstorm and heavy rain. We sit in the kitchen listening to stories of this emptied land. Monareng’s uncle gives us each a horn of a kudu. My special powers become doubled. In the morning we are glued to the TV watching the funeral unfold. It is just past noon and the casket is about to be lowered when the camera suddenly focuses on the Qunu landscape, respecting the family’s wishes that this moment not be broadcast. We feel cheated and drive back to Johannesburg sulking. Monareng remains behind. Passing the Suikerbosrand River we stop to throw in a few coins and report our departure. Johannesburg is not welcoming; in fact the city is hostile. That evening my sleep is restless and my dreams haunted by unfamiliar ghosts. I blame it on the horse tooth and the kudu horn. In the morning I leave the city for a two-week holiday. Passing the Suikerbosrand River I stop to throw the tooth and the horn into it. No more special powers. I feel lighter and happier.

Gabi Ngcobo is an independent curator and cofounder of the Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR), Johannesburg. This article was first published in the October 2014 issue.