Milan, 1959. A group of young artists comprising Gianni Colombo, Davide Boriani, Gabriele De Vecchi and Giovanni Anceschi establish Gruppo T. The following year they are joined by Grazia Varisco. ‘T’ as in ‘Time’, intended to be understood as motion and transformation, investigated in a spatial dimension. The members of Gruppo T worked together for about ten years before going their separate ways, continuing their research independently.

From his first solo show, Colombo created works that required activation on the part of the viewer

They were a motley group, looking for a phenomenological approach in which the interaction between work and the space around it is fundamental, as was the use of industrial materials, neon, elastic strings, modular structures. Rather than the fash ionable Bar Jamaica – then closely associated with artists of the older generation, including Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani – Gruppo T would meet at the Bar Titta.

They wanted to stand out; they were Rockers, as Giovanni Anceschi once said. Despite this, they were not at a loss for contacts and conversations, thanks to their collaboration with Manzoni at the Galleria Azimut (founded in Milan by Manzoni and Enrico Castellani, the experimental gallery’s eight-month existence spanned 1959 to 1960). Fontana was their first collector, and their works were produced as multiples in a nod to the production techniques then favoured by industrial design, but also to distance the works from the artworld’s cult of the author.

Right from his first solo show, Miriorama 4 (1960), where he displayed a series of kinetic works that required activation on the part of the viewer, Colombo (1937–93) created works in the form of environments, situations, structures, itineraries and passages. They were apparatuses that worked autonomously, establishing their own set of rules. From the early transformable objects like Rotoplastik, the kinetic Strutturazioni Pulsanti from the early 1960s, works made from lighting effects like Cromostrutture, 0-220 Volt (1973–7), After-Structures (1964–7) and Zoom Squares (1967–8), and environments such as Strutturazione Cinevisuale Abitabile (1964), to the well-known Spazio Elastico (for which he won an award at the 1968 Venice Biennale), the Milan-born artist presented artworks that required the direct participation of the user, an involvement of the body and mind within rules that must be respected, with variables set in motion by the creator.

Colombo set out to stimulate eyes, minds and bodies

“I’ve always said that my works have the character of a self-test. They weren’t made to obtain information, but to emancipate the viewer from his state of perception, making him aware of what concerned him,” Colombo stated in an interview with Jole De Sanna published posthumously in 1995.

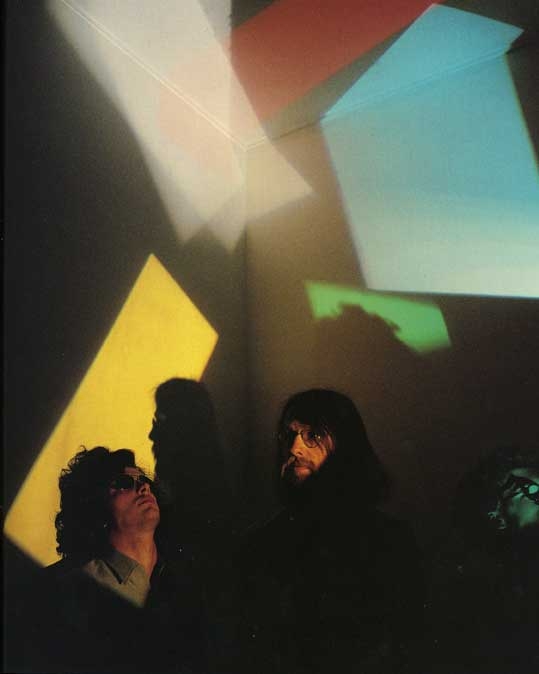

Colombo set out to stimulate the eyes, minds and bodies of those who experienced his works. He did not want to create purely visual phenomena involving light vibrations or kinetic effects, but rather to challenge consolidated moments of perception on every level. Spazio Elastico is composed of a darkened cube-shaped space, in which a grid of moving fluorescent elastic strings lit by black light reveals the basic stereometry of its geometric form.

The effect is akin to seeing a photo negative, where the relationship between black and white, line and volume, is inverted with respect to any sense of the ‘real’; where presence is transformed into absence, emptiness into fullness. Consequently, viewers find themselves immersed in an unstable space that establishes a feeling of estrangement and disorientation.

Colombo was drawn to the idea of transformation: an unexpected paradigm in which space acquires the ability to show us the way we experience it

In other series, such as Topoestesie (1977), Bariestesie (1974–5) and Architetture Cacogoniometriche (1978), the artist manipulated architectural space by designing oversize angular structures which visitors were invited to traverse, with the structure then tilting or tipping to alter the viewer’s sense of balance. These are devices that question repetitive and unconscious acts – the practice of walking or climbing a ladder or staircase for example – that determine the direction and attitude of the body.

Almost 20 years after the artist’s death, Colombo’s work is making a considerable comeback. Most recently in the form of a February solo show at Greene Naftali in New York, and its inclusion in the summer group exhibition Push Pins in Elastic Space curated by the artist Gabriel Kuri at Galerie Nelson-Freeman, Paris.

His work has also been the subject of major solo exhibitions at the Neue Galerie and Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (2008), at the Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich and at the Castello di Rivoli, Turin (both 2009). His works have additionally appeared in major group exhibitions such as the 16th Biennale of Sydney (2008), the 54th Venice Biennale (2011), Italics (2008) at Palazzo Grassi, Venice, Erre, Variations Labyrinthiques (2011) at the Centre Pompidou, Metz, and Ghosts in the Machine (2012) at the New Museum, New York.

‘My works were made to emancipate the viewer from his state of perception’

Of course, it’s not as if his work was unknown before all this. During his lifetime it was included in seminal exhibitions such as Kunst Licht Kunst (1967) at Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Lo Spazio dell’Immagine (1967), in Foligno, the Trigon biennial, Graz (1967 and 1973), the controversial Documenta 4, Kassel (1968), Räume und Environments (1968) at the Städtische Museum, Leverkusen, and Die Sprache der Geometrie at the Kunstmuseum in Bern (1984).

But it was in the wake of his 2006 solo exhibition, Gianni Colombo: Il Dispositivo dello Spazio, curated by Marco Scotini (who since 2004 has been director of Archive Gianni Colombo and who curated the Castello di Rivoli show with Documenta 13 director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev) at the Rotonda di via Besana in Milan, that a new reading of his oeuvre began to emerge.

That show marked a shift from the idea of a constructivist, analytical and technological Colombo, attributed to him over the years by various Italian critics, to one that placed more emphasis on his dadaist-surrealist links, which were formulated by the artist himself as a part of a thesis on Max Ernst and Dadaism, completed as part of his diploma at Milan’s Accademia di Brera in 1959. For Colombo, Ernst was not only a leading pioneer of the plastic arts revolution but also a master of subversion.

From the German artist Colombo learned not to be afraid of playing games or of the sense of estrangement caused by an unpredictable situation that interrupts the accepted structures of real space. And so, from the dadaists he adopted the idea of teamwork (both as a member of Gruppo T and in his subsequent work) and a refusal to accept art as a sublimated activity that separates the perceiving subject from his or her own body or surroundings. It is from this that the ironic-playful component present in his works arises.

Colombo was drawn to the idea of transformation: an unexpected paradigm in which space acquires the ability to show us the way we experience it

Colombo was drawn to the idea of transformation: an unexpected paradigm in which space acquires the ability to show us the way we experience it, transforming the spectator into the object of art itself. And it is here that the artist places himself in dialogue with the nonsense of Buster Keaton, and that the transformability of space becomes his stylistic feature.

Colombo loved the slapstick comedies of early silent film. In a photomontage created with Gabriele De Vecchi for the exhibition Amore Mio in 1970, he composed a projection made up of frames from movies by Mack Sennett, Luis Buñuel, Fritz Lang and Buster Keaton. In Studio Goniometrico (1977) Colombo redesigned the prefabricated home Keaton had wrongly assembled in his short One Week (1920), presenting it alongside Topoestesia and a frame from the film. In slapstick comedies the settings relate to the bodies of the characters who inhabit them, where the former are transformable and the latter malleable. Both are the site of action and experimentation.

The body is the other aspect that determined a rediscovery of Colombo. As the philosopher and critic Jean Louis Schefer wrote, in Colombo’s devices the body does not guide the actions; it simply absorbs them. Another critic, Guy Brett, went further, likening the way in which the work of Colombo unites the eye and the body to that of Brazilian artist Lygia Clark. Despite different approaches, both artists investigate the way in which the manipulation of physical behaviour allows the body to recuperate an awareness of itself.

Besides the curators and critics, Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson has stated on various occasions that Colombo’s work deserves more consideration, on the grounds that the ideas the Italian experimented with a few decades ago remain pertinent to contemporary artistic discourse. At one point Eliasson, as he revealed in an interview with curator Marcella Beccaria, thought about including a work by Colombo in one of his own solo exhibitions, to illustrate the existing dialogue and symbiosis.

For Scotini, “In Colombo there’s something that goes beyond Eliasson’s ‘orientation devices’. Perhaps an attitude that is much closer to Carsten Höller’s ‘laboratories of doubt’ or ‘confusion machines’. Or again the ‘powerless structures’ of Elmgreen & Dragset, with their declared Foucaultian background. Indeed, the duo’s alterations to the white cube at Portikus at Frankfurt in 2001 can be viewed as a sort of development of Colombo’s project at the Kröller-Müller Rijksmuseum at Otterlo in 1980. In the former case the reduction of a perfectly rational structure into a flexible space with a curving floor and skylight; in the latter, the distortion of four pathways that follow those made in 1937 by [Henry] Van de Velde in the Dutch museum.”

Even Maurizio Cattelan, an artist absolutely distant from Colombo’s working method, is unable to resist referencing the earlier artist. Cattelan recently photographed the collector Dakis Joannou in the same pose and with the same work in which the photographer Oliviero Toscani had photographed Colombo in the late 1970s.

Yet, despite this rising interest, much remains to investigate regarding Colombo’s oeuvre. All his early ceramic works, for one thing, which were acquired by Thomas H. Lee and Ann Tenenbaum. And Colombo’s esteem for and friendship with the Irish artist James Coleman during the 1960s, the only trace of which lies in an extraordinary correspondence held in the Archivio Colombo in Milan.

Gianni Colombo’s Spazio Elastico (1967–8) is included in Zero, Museu Oscar Niemeyer, Curitiba, through 3 November. Two other installations, Topoestesia (Itinerario Programmato) (1965–70) and Strutturazione Pulsante (1959), are on display at the Museo del Novecento, Milan

This article was first published in the October 2013 issue.